Born and raised in Virginia,

By Cynthia Oi

Dana Ireland grew up to become

a beautiful, vibrant person

who lived life fully

Star-BulletinSPRINGFIELD, VA. -- From the moment she died on Christmas Day 1991, Dana Ireland has been buried in legal documents, autopsy reports, police radio transcripts, depositions, confessions and recantations of wrongdoing.

She has become a symbol, a victim, a rallying point for well-meaning champions of justice. In news stories, she is reduced to a recitation of statistics: a 5-foot-4, 110-pound, 23-year-old recent college graduate.

Blurred through the years is the real person.

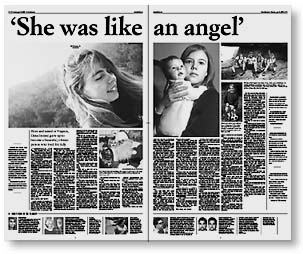

Her mother's favorite photo of Dana reveals elements of her soul. Her long hair swirls around her radiant face, a smile teasing her lips. Behind her, mist skims the forested Virginia hills where she's hiking. She looks vibrant, clean, sure of her body and its strength, joyful to be outdoors.Dana's family and friends in Virginia and in Hawaii keep her humanity alive through their memories. She was beautiful, they say, shy, kind, loyal. She was an athlete, a sweet daughter, a tomboy, an angel, an innocent, an average girl.

John, Louise and Sandra

Louise Ireland, 43, mother of a 13-year-old daughter, had been feeling bloated. She had missed a period, but her gynecologist had told her that at her age she wasn't likely to have any more children. Chatting with a neighbor, she mentioned her discomfort."She said, 'Oh, Louise, you're pregnant!' I told her she was crazy. How could I be pregnant?" Now 75, Louise flushes as she remembers the conversation from more than 30 years ago. She lets her husband take up the story as they sit in their neat living room.

"I came home from work one day and Louise was sitting in the kitchen with a drink. And that was very unusual," says John. "I knew she had been to the doctor that day, so I thought it was something very serious. So I asked her, 'What did the doctor tell you?'

"She started crying. She says, 'I'm pregnant.'

"I grabbed the bottle and took a big slug. And then I looked at her and said, 'Well, who the hell is going to cut the grass this summer?'"

He chuckles, she flushes again and he admits that even pregnant, his wife mowed the lawn.Louise was a little embarrassed about her pregnancy. She is of a generation that is more discreet about such things. But when Dana Marie was born Dec. 12, 1968, Louise was ecstatic.

"She was my pride and joy," she says. "This was the best thing that ever happened to me in my life."

Dana grew up in a trim, hilly neighborhood in Springfield, a Virginia suburb about 11 miles southwest of Washington, D.C. The Irelands have lived in the three-bedroom home for 37 years.

Springfield is one of those towns that flows from churning interstates to quiet streets with few boundaries to mark where one community begins and another ends.

Just off the "mixing bowl" -- a tangle of freeway entrances and exits -- a huge mall muscles up against smaller retail strips. Along the main drags, fast-food plazas alternate with gas stations, town houses and apartment buildings. Industrial parks abound.

Old Keene Mill Road, a rustic label for a four-lane highway, dips and rises past Accotink Creek and the Irelands' neighborhood.

Dana attended Keene Mill Elementary, Washington Irving Middle School, West Springfield High, Radford University, about 250 miles away, and George Mason University, about eight miles away.

Louise was a stay-at-home mom who "always made sure I was there" when Dana got back from school.

John got a kick out of his younger daughter.

When she was about 3 years old, she asked him what her middle initial M stood for. "Magoo," he told her. Soon the neighborhood kids picked up the nickname.

"She didn't pay attention to it much until she saw a cartoon with Mr. Magoo in it. Then she said she didn't want that name. But it just stuck," he said.

Dana was obedient, but when something didn't sit right with her, she could be stubborn.

One day, when she was about 8, she refused to go to school.

"She was sitting here on the couch and she was pouting," John says. After some coaxing, Dana explained herself. It seemed that Jewish students were being given a religious holiday that day. If they didn't have to go to school, she wasn't going either, she said.

"They have their holidays, just like we have Christmas," John told her.

But they get Christmas off, too, she said.

"You couldn't argue with that," he says.

She was loyal, John says. When the coach of the high school soccer team tried to recruit her, she refused because he would not give her soccer club teammates a tryout."She was very particular about her friends," John says. "They were all very nice people -- I don't know one of them that I wouldn't have approved of."

Oh, sometimes there were parent-child differences, but not anything big. "One I did have with her was the music she listened to." John can't identify the artists or songs, just that "she liked the normal rock kids were listening to and I couldn't stand it."

Another disagreement was about an allowance; Dana didn't want one.

"I tried to talk her into it. Maybe she figured she'd get a little more if she came to scrounge money from me," he says, laughing.

Mostly, though, Dana earned her own spending money, managing swimming pools and working as a lifeguard and at a spa.

She was "an average girl," her dad says. She didn't watch a lot of television, except for programs about Hawaii, water skiing, surfing and other water sports. She didn't read a lot, except for National Geographic magazine, which fed her curiosity about the larger world.

Sitting still wasn't her style. "She'd run and run, do exercises, skate, then come home and start all over again," Louise says.

"I don't know whether she had some kind of premonition that she wasn't going to be here very long, but she really tried to get everything she could out of life."

Dana was a tomboy, but a neat one. Her jeans, shorts and shirts -- she seldom wore a dress -- had to fit right "and she had to have the right kind of shoes," Louise says. Dana didn't wear makeup, wanting "to look natural."

Staying fit was important to her. "She was very particular about her diet," Louise says. "She didn't smoke. I understood she drank once when she was at Radford (University) and it made her so sick she never touched it again. She never touched drugs."

The younger girl deeply admired her sister. "She always kept her hair long because Sandy had long hair. She wanted to be just like her sister," Louise says.

Their age gap meant that they spent only five years under the same roof before Sandra left for college.

"We put Sandy on the plane to school in Florida the same day Dana entered kindergarten," John says.

Still they were very close, Louise says. Sandra, in fact, named Dana. "I liked Marie, but Sandy liked Dana," she says, and Dana she was.

The sisters were physically alike, too. "Sometimes I can't tell which is Sandy and which is Dana," says Louise as she looks at photographs of the two.When Sandra moved to Hawaii, the Irelands visited her almost every year. Through Sandra, Dana grew to love the ocean and the outdoor island lifestyle.

After she finished college, she went to stay with Sandra and her boyfriend, Jim Ingham, (they have since married) in Vacationland, a beach community where full-time residents mixed with snowbirds. The elder Irelands usually rented a home there for their visits.

The last day the family spent together was Christmas Eve, 1991. They went on a shopping expedition to Hilo to buy gifts.

"Dana was driving," Louise says, "and out of the blue sky, she said to me 'Momma, if there's no heaven, when you die that means the good and the bad go to the same place.' I said, 'Well, Dana, whatever happens to you or anybody I think God will take care of you.' I don't know why she said that."

Louise didn't get her younger daughter any gifts. "We were going to Kona the next day and she said she wanted to get some things over there."

For her mother, Dana had bought a shirt, a tray with a Hawaiian design and "a little handbag with sequins all over." They have become Louise's keepsakes.

John's gift to Dana was $400 in traveler's checks to be used on a trip with Sandra to Australia. He never got to give them to her and to redeem them, American Express required a copy of Dana's death certificate.

"I had a heck of a time with those," he says.

When John remembers Dana, she is as she was just before her death: a vigorous, lovely young woman. "Yep, yep," he says, "that's how I think of her."

Old friend, new friend

Valerie Oliver knew Dana for most of her life. Mark Evans met Dana about three months before she died.She had a profound effect on both their lives.

When Valerie and Dana were in the sixth grade, Valerie's family moved in across the street from the Irelands. The two girls attended the same schools, their friendship deepening as they grew older.

Like Dana, Val is blond, slim and athletic. In the evening of a spring day, she is gardening at her home in Springfield where she lives with her husband, Richard Dexter, who also was Dana's classmate. Val, now a human resource manager, and Richard, a schoolteacher, were part of a group of Dana's friends, hanging out and hiking many miles together.

"Dana loved life," Val remembers. "She loved the outdoors -- hiking, biking, all those things. She liked the challenge."

She was "a tremendous athlete. You look at her and she's a teeny-tiny person, but she was so physically fit, very strong," Val says.

"She was a tomboy, an absolutely beautiful tomboy," she says. Until they went to their senior prom, "I don't think I'd ever seen her in a dress."

That night, she wore makeup and "had her hair all done up. I said, 'Dana?' I almost didn't recognize her," she says, laughing. "She turned quite a number of heads."

Dana's death made Val and Richard re-evaluate their lives. They took off, traveling around the world for almost three years.

"A lot of our decisions about our life were based on how Dana lived her life," Val says. If the weather's nice, "I think what would Dana be doing? I gotta enjoy this beautiful day.

"When I'm down, or it's oh, so hard to get up to go to work, I think: Live your life like every day is your last, because you never know."

The summer before Dana died, as she was preparing to move to the islands, the two women discussed their futures.

"Dana knew she wanted to go to Hawaii. She'd been talking about it all her life, but it was hard for her to leave her mom," Val says. "She did have second thoughts -- 'Am I doing the right thing?' But she had wanted to do it for so long.

"Dana led an incredible life. People who live five times her lifetime didn't get the things out of life that she did."

When she remembers her friend, she pictures her on top of a mountain called Old Rag near the Shenandoah Valley where they often hiked. "She's sitting in the sun on a rock, enjoying being alive and healthy."

Dana wasn't vain about her beauty. In fact, she hardly recognized it, Val says.

"She was childlike and shy. There were always three or four men who were in love with her. But she just wanted friendship. She wasn't ready for the serious stuff."

When Sandra introduced Mark Evans to her sister, he was pleasantly surprised.

He had known Sandra for years. "I always kind of had a crush on her," he admits, "but she had Jim. Then here comes Dana and she's a spitting image of Sandy. It was like, thank you, Lord, there are two of them!"

Mark -- a carpenter, surfer and father of two little girls -- was the friend Dana had biked over to invite to dinner that Christmas Eve afternoon.At 35, he is movie-star handsome, buff and tan. He has lived on the Big Island for 12 years. The house in Opihikao, which he shares with his daughters and his companion, he built himself.

As their friendship grew, Mark realized that Dana was different.

"She was really innocent," he says, sitting on his porch in the twilight. "So pure. She didn't know anything about anything.

"It wasn't like let's start a relationship and make love. Nothing like that at all. It was the way a relationship should start."

Dana and Mark spent time bodyboarding, swimming, surfing and "hanging out."

One day, he took her to Waipio Valley.

"We took a really beautiful hike, back to the waterfalls. She was so strong and yet she was so graceful. It was a beautiful day and she was like an angel."

After Dana died, he reassessed his values.

"You see the way we live," he says, waving his arm at his house. It has no doors and walls on only two sides. "I live in such an open lifestyle and still everything is good. I don't lock up because I think someone's going to steal. Hey, take my stuff if you need it.

"My kids walk to the mailbox" down around the corner from the house. "I can't live in fear. Something like that might never happen again, then it might happen tomorrow. I might drown while surfing; a shark could attack me. But this is my life."

Dana's death has left Mark feeling incomplete.

"She was a great person. It goes over and over in my mind, where would my life be? There's no telling if Dana and I would have worked out, but I wonder. We were really good together."

He stops to look at the full moon rising over the ocean.

"We kissed only one time," he says softly, eyes glistening. "Yeah, I loved her."

Dana loved to run, to bike and hike, to skate and swim. Fate is merciless in that death would find her because of the pleasures of her life.

When she left Mark's house that afternoon, he suggested that he drive her back.

"No, it's a beautiful day," she told him and climbed on her bike.

So she pedaled away along the coastal road, the December sun warm, the air salty with sea spray -- Dana smiling, lithe, tanned, lovely, alive.

Courtesy of John and Louise Ireland

3-year-old Dana on the patio of the

Irelands' home in Springfield, Va.

Tuesday, June 8

Blurred through the years is the real Dana. She lives on, though -- beautiful, shy, kind -- in the memories of those who knew her. The innocent. The indicted. Anatomy of a murder. The what and where of the attack. Who's who in the Dana Ireland tragedy.

Wednesday, June 9

Help came too late for Dana Ireland. From the moment she was hit by her attackers' car until the time an ambulance reached her, more than two hours passed. Here's how minutes -- and a life -- were lost.

Thursday, June 10

Life has gone on since the Dec. 24, 1991, attack. Memories have faded. Witnesses have scattered. But each twist and turn in the seven-year bid to bring to justice those responsible means fresh injury, not only to Dana's family but to witnesses whose lives have been put on hold by this on-again, off-again case.

No Frames: Tuesday, June 8 | Wednesday, June 9 | Thursday, June 10