Hokule‘a

worthy heir to

stunning feats

Ancient seafarers crossed and

re-crossed the greatest ocean on

Earth, spreading their culture

over a vast areaNon-instrument navigation

By Susan Kreifels

Star-BulletinIt was born of a dream to prove the extraordinary skills of their ancestors, the navigators who used only the stars and a oneness with the sea to settle the vast Oceania.

It was also to prove themselves.

But the dream-makers never imagined the voyaging canoe Hokule'a would lead a renaissance of traditional Hawaiian and Polynesian cultures, creating a stronger sense of identity and direction among Pacific island people.

"I never dreamed in a hundred years this could happen, this rebirth, a rethinking of their heritage," said 79-year-old Wallace "Uncle Wally" Froiseth, the oldest member of the Hokule'a crews and with the canoe since its first sail on March 8, 1975.

A quarter-century later, Hawaii's three traditional voyaging canoes -- the Hokule'a, which has logged close to 100,000 miles (2 1/2 times around the equator), followed by the Hawai'iloa and Makali'i -- have retraced the migration routes of Polynesian ancestors. The only island unvisited is Rapa Nui.

The Hawaiian voyagers have been greeted with outpourings of affection from Polynesians and Micronesians, who share the same "canoe ancestors" -- the only deep-sea sailors in the world for at least 2,000 years, starting their explorations of the Pacific in the second millennium B.C. and settling every inhabitable island.Their feat astounded 18th century explorer Capt. James Cook, who called Polynesia "by far the most extensive nation upon Earth." Cook was amazed that native people on opposite edges of vast Oceania -- from New Zealand to Rapa Nui -- looked the same and spoke similar languages.

Hawaiian historian and artist Herb Kane, University of Hawaii anthropologist Ben Finney and waterman Tommy Holmes envisioned the Hokule'a as proof that ancient voyagers, without navigational equipment, spread from Southeast Asia using seasonal westerly winds to discover the Pacific islands. Easterly winds took them back.

Although the animal and plant life and Lapita pottery found in the Pacific islands could be traced to Southeast Asia, skeptics like Thor Heyerdahl believed the ancestors floated from South America with the easterly tradewinds. In 1947, Heyerdahl did so on a balsa raft, starting in Peru and landing in the Tuamotu Archipelago in Central Polynesia.

Earlier skeptics believed the discovery and settlement of the Pacific islands was accidental, by exiles or those lost in storms.

The Hawaiian navigators proved Heyerdahl and other skeptics wrong.

Finney, co-founder of the Polynesian Voyaging Society, has researched the immigration routes of the ancient navigators. In the "History of Cartography," Finney writes that by at least 1500 B.C., seafarers with roots in the Philippines and Indonesia had reached Bismarck Archipelago off the northeast coast of New Guinea.

Within a few centuries they had moved east to Fiji, Tonga and Samoa. Archaeological and linguistic evidence suggests they may have lingered in this region for up to 1,000 years.

They then sailed farther east to the Cook, Society and Marquesas islands, settling some of them as early as 500 B.C. From there, they spread in three directions: Hawaii, Rapa Nui and New Zealand. The time of Hawaii's settlement ranges from A.D. 200-750; Rapa Nui, A.D. 400-800; and New Zealand, A.D. 800-1200.

Micronesia was populated in two movements. About 1500-1000 B.C., seafarers are believed to have sailed from the Philippines to the Mariana Islands, including Guam and Saipan, and to Belau and perhaps Yap in western Micronesia. Centuries later canoes sailed north from Melanesia to Kiribati and the Marshall Islands. Then they headed for the Caroline Islands, meeting up with Yap and Belau.

The voyagers spread the Austronesian language, traced to southern China, from Madagascar to Rapa Nui -- two-thirds of the world. It was the most widespread language family on Earth until Western Europeans developed their own seafaring technology, which led them to Polynesia.

Under centuries of Western colonial rule that banned traditional ways of life, the art of long-distance voyaging was almost lost. It already had died in Hawaii, but a few star navigators remained in Micronesia. Finney asked Mau Piailug of Satawal to teach the Hawaiians traditional voyaging. Piailug navigated the first Hokule'a voyage in 1975 and taught Nainoa Thompson, who became the Hokule'a captain.

Next March 8, the Hokule'a will celebrate its 25th anniversary with a sail through the entire state. By then, Thompson will have passed on the canoe's leadership to a new generation of captains and navigators.

His hope: "That they continue to dream."

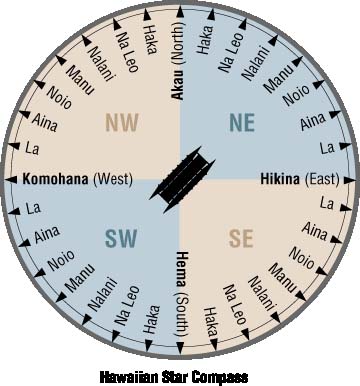

To guide them across the vast Pacific, ancient navigators created mental compasses which helped orient their ships to the rising and setting points of stars. From this, Hawaii's premier navigator, Nainoa Thompson, developed the Hawaiian Star Compass. It features 32 equidistant directional points around the horizon, with each point 11.25 degrees from the next point (11.25 degrees x 32 points = 360 degrees). It, along with other navigational elements like the sun, ocean swells, clouds and birds, will be used during Hokule'a's journey. Non-instrument navigation

THE STARS

Stars rise and set in particular directions on the horizon. For example, a star that rises on the NE horizon, travels across the sky and sets on the NW horizon. Thus, the rising and setting points of stars are clues to direction. Recognizing a star as it rises or sets and knowing in what direction it rises and sets gives the navigator a directional point from which he can orient the canoe and head in the direction he wants to go.

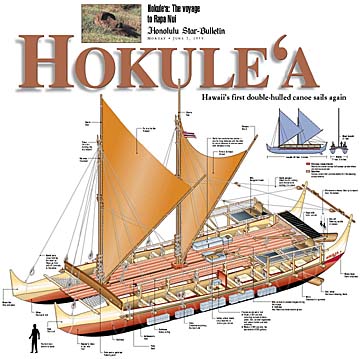

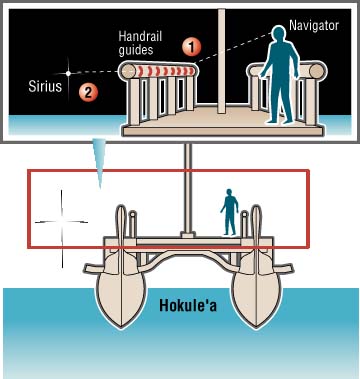

USING THE CANOE AS A COMPASS

1. The handrails on the Hokule'a have eight vertical grooves carved into the wood, filled with bright red epoxy resin. These grooves are compass points, providing the navigator with references to use when viewing the stars in the night sky near the horizon.2. Using the star Sirius as an example, the navigator stands in a preselected point at the right side of the back of the boat. Assuming he wants to head in a certain direction (in this case, south), he knows he must keep the canoe lined up with Sirius and one of the grooves on the rail.

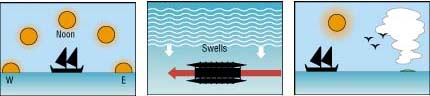

THE SUN

Twice a day, at sunrise and sunset, the sun gives a directional point to the traveler, rising in the east and setting in the west.

OCEAN SWELLS

Swells are waves that have traveled past wind systems that created them. The navigator can orient the canoe by using the direction of swells as a guide.

CLOUDS AND BIRDS

The shape, height and color of clouds foretell the weather, and they also accumulate over land. Also, the presence of seabirds indicates nearby land.Sources: Dennis Kawaharada and the Polynesian Voyaging Society; "Hawaiian Canoe" by Tommy Holmes; "Atlas of Hawaii" by Sonia P. Juvik and James Juvik; Hokule'a crewmembers Nainoa Thompson and Kamaki Worthington.

HOKULE'A WEB CAMERA

The Hokule'a has a Web camera on board.

Access images during the voyage at:

Web camera to access images during the voyagehttp://leahi.kcc.hawaii.edu/org/pvs