A quest that began two decades

By Suzanne Tswei

ago results in rediscovering the

Hawaiian method of

kapa making

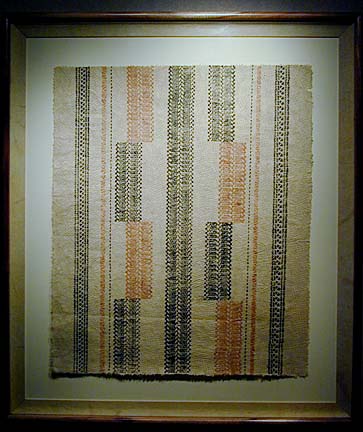

Special to the Star-BulletinFOR a year, kapa master Puanani Van Dorpe has had her mind only on a particularly complicated multicolored kapa that hasn't been produced for more than a century in Hawaii. When her husband Robert gently pries her away from her kapa-making to speak to a reporter on the phone, she does her best to deal with the distraction.

She's polite and answers all the questions, but after about 15 minutes, her mind is right back on her work. She worries about being away too long from the mulberry bark left soaking in water. When the reporter asks if she wants to get back to work, her answer was immediate and unequivocal.

"Oh, yes, yes, yes, please. Oh, thank you," she says, like a grateful child who is excused from an unappetizing dinner. She dashes off without hesitation and soon the steady, rhythmic beating of kapa echoes gently in the background as her husband talks about her all-consuming passion for the Hawaiian tradition of making kapa for more than 20 years.

ON EXHIBIT

What: "Kuku Kapa, Making Kapa," by Puanani Van Dorpe

Where: East West Center Gallery

When: 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Mondays through Fridays; noon to 4 p.m. Sundays through June 18

Cost: Free, guided group tours may be arranged by calling 944-7584

Call: 944-7341

"Pua is happiest when she is making kapa -- that's her life, that's what she's interested in. You can say she's a bit of a recluse. She's perfectly happy being alone, making kapa all day.

"She's not interested in being on display, being admired for doing something the ancient Hawaiians did. She doesn't want to be a curiosity for the tourists to gawk at. When she has to talk to strangers, that can be bit torture for her. But if she's talking about kapa to people who are interested and have knowledge or experience in it, then she's perfectly fine."

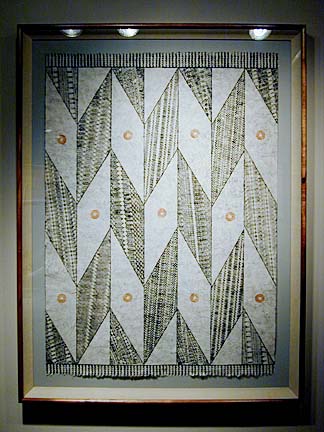

Van Dorpe recently had to endure public attention when her first solo exhibit opened at the East-West Center Gallery. The exhibit, which runs through June 18, focuses on a wealth of Hawaiian kapa, tools and raw materials, with an education display with photographs and texts.The show also allows a glimpse into the painstaking steps Van Dorpe undertakes in duplicating the once-lost craft. She uses no short cuts or modern conveniences. One photograph shows her scraping the outer bark of the mulberry tree with a shell implement. Another shows her biting the bark with her teeth to strip the bark.

To make a black dye for stamping designs on kapa, Van Dorpe burns Kukui nuts to collect the ash and soot, then mixes the black powder with the sap-like juice squeezed from the bark of the kukui tree. To dye a whole piece of kapa black, she steeps it in the mud of a taro field.

"There is a reason she doesn't use a Mix Master (to make dyes.) Because it doesn't work -- you don't get the same results. The ancient Hawaiians didn't use it, they did everything by hand, little at a time, and that's how Pua does it. It takes her hours and hours to make a little bit of dye," her husband said.

Anthropologist Roger Rose, who formerly oversaw the kapa collection at Bishop Museum when Van Dorpe researched the subject, vouches for her exacting technique."She works just like a scientist. She's very methodical, everything is done according to strict protocol, like scientific experiments, and she documents everything she does. Every result of her experiments is recorded," he said. "She's a real treasure, a real inspiration to others who are trying to revive the lost culture of Hawaii."

Van Dorpe gathered information from many sources: books, legends and chants, museum examples here and on the Mainland. She consulted scientists and Hawaiian scholars, but for the most part she had to reinvent the craft because there were no living Hawaiian kapa makers to teach her the details.

"You can read a book, but the book really doesn't tell you how it's done exactly, the step by step. You have to do it yourself to find out. The books were written by people who were observers, not people who actually made the kapa," she said. "I basically had to figure things out by myself. It's all hands-on experience, and I had to make a lot of mistakes."

The basis for Van Dorpe's interest in kapa came in the late 1960s, when she and Robert lived in Fiji, where he worked as a developer. He found a group of women on the island of Vatulele producing kapa to trade for food and kerosene, and encouraged his wife to visit them."I was playing golf everyday, four hours a day, seven days a week. Golf was my life. I really wasn't that interested when my husband suggested I go visit these women. But he kept saying it's a once-in-a-lifetime experience, and I should go and see for myself before it's gone," she says.

To please her husband, she went -- in a small wooden boat carrying pigs and bananas -- and the week-and-half trip changed her from a pampered wife living a life of leisure to a full-time practitioner of a craft that demands back-breaking labor.

"I never played golf again. I realized the Hawaiians lost their culture, and I wanted to find out what that was. That began my quest 24 years ago," says Van Dorpe, who is one-eighth Hawaiian.

Her effort to replicate Hawaiian kapa began in earnest when the couple moved to Maui, where Robert worked to develop a cultural park for Amfac. He provided valuable support by spending a small fortune to have traditional stone and wood implements made to his wife's specifications, planting acres of wauke to provide the raw material, paying $50-an-hour museum fees for her to conduct research and buying a collection of authentic Hawaiian kapa for her to study.

Now retired, he continues to help document his wife's progress and provide a stress-free environment to allow her to concentrate on her work. The couple now lives in Honaunau on the Big Island."I bought a microscope for her for Christmas one year," he said. "She was always saying she could never be sure that her work is as fine a quality as the ones made 200 years ago. The only way for her to tell is to compare them under the microscope. When her pieces matched up to the ones in Bishop Museum, boy, that was really something."

But Van Dorpe, in her early 60s, isn't finished, yet. "I am at a stage where I am never satisfied. I go to bed thinking kapa, and I wake up thinking kapa -- what am I going to do today to find the answers. If I had two more lifetimes, I might figure out the answers."

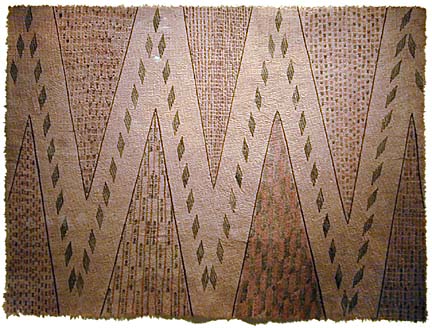

PUANANI Van Dorpe has rediscovered 14 different kapa-making techniques, five ways to dye kapa and numerous other methods that the Hawaiians employed in producing cloth made from mulberry tree bark. Traditional methods and tools,

like a shark-tooth knife, are used

to create fine piecesVan Dorpe is her own harshest critic, sometimes destroying pieces that do not meet her expectations. She adheres to strict standards she sets for herself -- by using only the tools and fresh or ocean water that were available to her ancestors before kapa-making died out in Hawaii in the late 1890s.

The result is authentic-looking kapa that can take several months to produce, not counting the time it takes the wauke (mulberry tree) to grow to the desired height of about 6 to 10 feet.

Careful trimming of all side shoots allows the wauke to grow into a single, straight trunk, and the harvesting is done when it reaches about an inch in diameter.

Van Dorpe uses a niho-'oki (shark-tooth knife) to cut along the trunk to begin peeling the bark in one whole piece. The bark is rolled in a bundle and left to soak in water to soften it. Then the outer, dark bark is scraped off with a wa'u (sea shell tool) to reveal the inner, white bark.

The inner bark is dried and bleached in the sun. At this stage, the bark is called bast, it can be either stored in bundles for later use or soaked in water again to soften it for pounding with wooden beaters. The first beating is done with a mole-mole (smooth round beater) on a kua pohaku (stone anvil.) The bark is beaten until it becomes several times its original size and again dried in the sun.

Van Dorpe's favorite method requires tearing the beaten dried bark into small pieces, which then are left in water to ferment. After the pieces become fermented pulp, she forms them into balls and beats them into a piece of kapa.

The fermentation method is unique to Hawaii and allows for a strong and fine kapa, according to Van Dorpe's husband, Robert. Without the fermentation, the kapa is beaten until it becomes the desired size and texture, but the fibers all run in the same direction. With fermentation, the fibers become interlocking, running in different directions, therefore forming a stronger cloth.

The watermark is another uniquely Hawaiian technique. The embossed designs, such as one derived from the triangular shape of the shark tooth, are beaten into the kapa with square-shaped wooden beaters carved with the designs.

The earth and a variety of flora provide the colors for kapa, ranging from a soft tobacco-stain brown to bright yellow. Dyes may be applied with a hala brush made from the pineapple-like fruit of the hala tree, or gently spread out by hand. One way to add dye involves cooking the dye and kapa, wrapped in leaves, in an imu.

Bamboo sticks with intricate designs carved on the ends, can be applied with paint to add more decorations. Kapa also may be scented with fragrant flowers and leaves, such as maile or 'iliahi.

Click for online

calendars and events.