NEIGHBORHOODS

Homesteaders

take charge

on Maui

Some will give up water

By Gary T. Kubota

and electricity to settle dry

Kahikinui -- with goals for

a community as well

as conservation

Star-BulletinKAHIKINUI, Maui -- Some 75 Hawaiian homestead applicants are giving up the comforts of running water and electricity to live along the remote, dry slopes of south Maui.

The Hawaiians will pay the state $1 a year for 99 years for the pasture land, and have agreed to help bring back the native forest mauka of their settlement at Kahikinui.

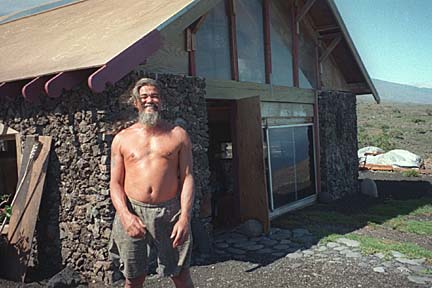

"We are so thankful. It is an opportunity to live on undeveloped land, much like our ancestors," said homesteader Tetoa "Mo" Moler.

"The bottom line is we have an opportunity to live in our own lifestyle."

Under the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act of 1920, some 203,500 acres of land were set aside in the islands for settlement by people with 50 percent or more native Hawaiian blood.

The settlement at Kahikinui, where the commission owns 22,809 acres, represents a departure from state policies, which usually require that electrical, water and sewer services be provided on homestead land before leases are awarded.

Faced with a growing list of more than 18,200 homestead applicants and limited money for development, the state Hawaiian Homes Commission decided to offer the option of settlement on undeveloped land.

"It's a choice among an array of homesteading opportunities," said Aric Arakaki, a Hawaiian Homes program planner.

Moler first applied for homestead land in 1984.

He and other native Hawaiians on Maui have spent more than seven years persuading the commission to allow the settlement.

The group has developed a native forest management plan to replant some 7,000 acres of upper Kahikinui, and a plan for a 100-lot settlement on 1,344 acres.

The commission has approved both plans.

Moler, a retired county fire captain, said the group is developing a cultural resource plan for the land on the makai side of Piilani Highway.

Under the plan, native Hawaiian settlers would be able to grow their own food and sell what they produce, including crafts.

Botanists once described the Kahikinui forest as so thick they had difficulty moving through it.

The forest has retreated dramatically since cattle ranching in the early 1900s. The lowlands have no trees, except for occasional clusters of wiliwili in gulches.

Sun-bleached cattle grass barely covers the rocky ground.

At upper elevations, near the 5,000-foot level, are stands of ohia and koa trees and 10 species of native birds.

Nene geese fly in V-formation on upwind drafts at higher elevations beside Haleakala, and a number of rare and endangered native plants grow in fern-covered gulches inaccessible to foraging animals.

On the land to be occupied by the homesteaders -- about a half-mile from Piilani Highway -- are heiau and the crumbling stone walls of houses once occupied by native Hawaiians.

Moler said homesteaders who have jobs outside the community for the most part will be relying upon volunteers and their own skills to build their houses.

The community has a committee that reviews the design of the homes to make sure the structures are safe, and requires the drawings to be approved by an architect.

Moler and his friends have built a house at Kahikinui as a model of what can be constructed on the land, using lava rock and the natural contour of the area for walls.

More than once a month, Moler loads a tank of drinking water on his truck and takes it more than seven miles to the model house, where he uses a hose to empty it into storage tanks.

Solar panels charge the 12-volt batteries that power the house's lighting and other conveniences.

The refrigerator and stove are gas-powered.

To earn money for the community, Moler and other native Hawaiians rounded up wild cattle in Kahikinui and sold them for $6,000. The group returned branded cattle to nearby ranchers.

"We're not a welfare state," Moler said.

"We want to be self-sufficient."