PBS show shares

haunting of internment

'Children of the Camps' shows

the ongoing healing of

six internedChildren of the Camps

Airs: 10 p.m. today

On: KHET/PBS

By Nadine Kam

Features Editor

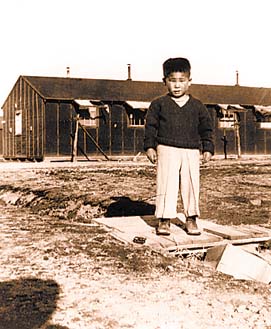

Star-BulletinTHE title of "Children of the Camps," a documentary set to air at 10 tonight on PBS, holds promise. Nearly 60 years after WWII broke out, there is still much to learn about the camps that imprisoned American citizens and permanent residents of Japanese ancestry. What this documentary amounts to however, is not a history, but eavesdropping on a group therapy session.

More than half of the 110,000 incarcerated after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, were children. In the program, six former internees, now in their late 50s and early 60s, reveal the ways this trauma continues to haunt them, affecting their relationships and perceptions about themselves.

The session, taped during a three-day "Children of the Camps" workshop at the Commonwealth Retreat Center in Northern California, is moderated by family therapist Satsuki Ina, producer of the documentary. What Ina -- a former Tule Lake child internee -- offers is a healing process to break more than 50 years of silence on the subject matter.

"Until we can talk about it and make a connection with the grief and anger, we will each still be unconsciously trying to get out of camp," said Ina, who was inspired by a similar documentary, "Color of Fear," in which minority men discussed the impact of racism on their lives.

In Ina's presentation, workshop participants express feelings of abandonment, anger and rage over the racism they felt even after they exited the camps. Other school children would taunt them by calling them "dirty Japs." When they looked to teachers for help, they found them in agreement with the tormentors, or looking the other way.

One woman, Marion Kanemoto, was 14 when she was imprisoned with her family. But she spent most of the war alone, overseas, after being traded to the Japanese in a prisoner-of-war swap. Although she attended school with other Japanese children, as an American she was never accepted.

Through others' loathing, the children begin to loathe themselves. One man, who eventually breaks down and cries, said that he woke up every morning wanting to mutilate his face so that he could look more like his Caucasian classmates.

The documentary's value is in pointing out the injustice. It is a message worth repeating because it seems to be a lesson lost in today's world. Society continues to breed hate for the "other."

What happened to these internees could happen "anytime to anyone," said workshop participant, Ruth Okimoto. "I'm apolitical. I try not to get involved in political things, but I know I'm very political. I have very definite views and have different ideals that I would like to see happen.

"I'm at a point now where I'm beginning to think I need to do something, myself, to make sure, in my small little way, that the things that happened to me as a child doesn't happen to another little child."

In one scene in which the group takes a walk along a beach, Okimoto finds six pieces pieces of bamboo driftwood which she came to see as "representing all of us who had been tossed about in the sea."

The driftwood became the centerpiece for the group, Ina said, with each person taking a piece of bamboo with them as they experienced closure.

There was no poetry in the camps, the documentary indicates, but the people made poetry through their spirit and determination to rebuild their lives.

Click for online

calendars and events.