"Regardless of what

is going on in the world,

we train."

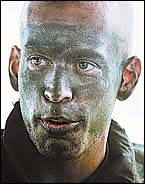

Capt. Tom Nelson

1992 WEST POINT GRADUATEAs NATO ponders putting

By Gregg K. Kakesako

troops on the ground in Yugoslavia,

isle soldiers train for the kind

of urban warfare the

Allies could face

Photos by Ken Ige

Star-BulletinRain clouds hang heavily on the distant Waianae mountain range as an Army captain patiently instructs one of his squads.

"You can't be afraid to use your weapon," Capt. Tom Nelson tells 10 members of Bravo Company as they stand in a small circle in the lush green tropical foliage.

It's a far cry from the bomb-marked province of Kosovo and from the Pentagon where a debate rages on whether to commit ground troops in a war that has been sustained for over a month by airstrikes.

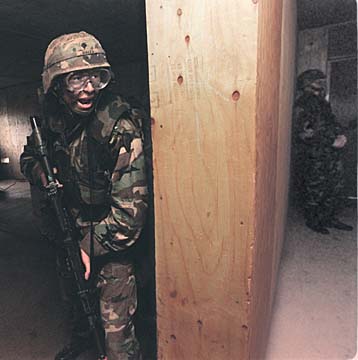

For several days, members of Nelson's company have been at the 25th Infantry Division's 6-acre urban warfare training site at Schofield Barracks, learning the techniques of close-quarters battle -- running across narrow streets, storming up barricaded stairwells, breaking into buildings and clearing out rooms.In a town that resembles those found in Europe, members of Bravo Company, 2nd Battalion, 3rd Brigade break down the technique of house-to-house combat where, unlike the vastness of Desert Storm, distance is measured in inches rather than in miles.

"When bullets start flying," says 32-year-old 1st Lt. Jim Gant, "you always hope you had more training."

"This is the hardest thing we can do," says Gant, Bravo Company's executive officer and a combat veteran of Desert Storm, as he describes what the Army calls Military Operations on Urbanized Terrain. Even before the crisis in Yugoslavia began, recent experiences in Somalia, Haiti and Bosnia-Herzegovina have made urban warfare an integral part of Army combat operations.

Because of the risk to civilians, the Army no longer can just blow away a wall from a safe distance with a tank or artillery as it did in World War II or Korea.

Soldiers at Schofield Barracks now practice fighting in the rubble of a simulated war-torn village.

Sgt. Roberto Colon, a squad leader in B Company, says he tells his soldiers "to be ready for anything. You can't be too ready."

"You have to keep yourself mentally alert and you have to practice ... always practicing."Colon, who went to Haiti in 1994 with the 10th Mountain Division, says the training "is realistic up to a certain point."

"The only difference is that you don't have civilians all over the place."

In Haiti, Colon, 26, says it was the patrols that scared him the most. "You didn't know what to expect."

In January 1995, 3,700 "Tropic Lightning" fighters were sent on a peacekeeping mission to Haiti.

As Nelson evaluates the performance of 1st Squad, led by Colon, he tells them: "The whole purpose is to make you better. If you saw something that is not right, bring it up.

"Be hard on yourself ... let's see what you did wrong."

Just a few minutes earlier the six members of Colon's unit stormed a two-story, hollow-tile building called South High School. It is one of 16 concrete buildings in a training complex that is in use 240 days a year.

The unit's instructions are simple. The top floor was secure. Their job is to enter the building from an outside stairwell and clear out the ground floor.

SIMULATION IS REALISTIC

Fully outfitted in 20-pound Kevlar flak jackets, with M-40 protective masks strapped to their hips, two 1-quart canteens on their belts, safety glasses and carrying 8.9-pound M-16 rifles, the soldiers scrunch themselves against a wall waiting for the signal to dash 20 yards across an open street to the "high school building."

Nelson watches. A few minutes later he tosses a yellow smoke grenade into the roadway, simulating cover for his squad. In the distance the rat-tat-tat of an M240 machine gun is heard. In actual combat, the machine gun would be laying down cover fire, forcing the enemy to withdraw.The soldiers scurry to an unprotected outside stairwell. But rather than move up the 10 metal stairs into the secured second floor, the squad gets stacked up in the open, uncertain what to do next.

Once in the darkened building, the soldiers run through the second floor down a staircase to the ground floor, where they begin the task of sweeping the eight rooms.

THE ADRENALINE SURGES

Lining up on either side of the hallway, the soldiers are supposed to cover each other's actions as they move toward the end of the building.As they barge into a room, each soldier is supposedly responsible for a small portion of the room. Battery-operated pop-up targets dressed in Soviet-style uniforms are there to confront them.

But it's dark. Some of the soldiers' goggles fog up. Adrenaline is pumping. In the confusion some members of the squad run by an open door, missing one room.

1st Lt. Jim Gant, Bravo Company's executive office, later asked the squad what should have been done.

Squad leader Colon notes that the next member of the team could have cleared the room if he noticed the mistake.

Gant also reminds the squad that they should never enter a room alone."With three individuals you better watch out. Two is pretty bad and one you need help."

He also notes that at one point there were too many soldiers in a room.

"How did that happen?" Gant wants to know.

He also reminds them that speed is essential in clearing a building.

"The longer you stay in there," Gant adds, "that gives the enemy more time."

DO IT AGAIN AND AGAIN

Each of the company's six squads will repeat this exercise at least three times today -- several times using blank ammunition and the final "test" a run-through with live .223-caliber bullets in their 30-round magazines. When dusk falls the exercise is repeated in the dark, with each soldier equipped with night vision goggles.

"I have faith in the people

I work with. They are good

people. They know what

they are doing."

Spec. Karl Feist

HAS SERVED IN THE ARMY FOR

MORE THAN THREE YEARSRoutinely, Schofield soldiers train at the urban warfare site about three times a year. And as pressure continues on the United States to commit ground troops in Yugoslavia, solders who will have to answer that call believe they are ready.

"I have faith in the people I work with," says Spec. Karl Feist, 21, who has been in the Army for more than three years. "They are good people. They know what they are doing."

Adds Nelson, a 1992 West Point graduate, "Regardless of what is going on in the world, we train."

Urban warfare training: PREPARING FOR ACTION

Where: South Range, Schofield Barracks

Size: 6 acres

Complex: 16 concrete buildings

Use: 240 days per year

Users: Army, Hawaii Army National Guard, Army Reserve, FBI, Drug Enforcement Agency

Completed: July 1993