Thirty years ago, Hawaii engineered a

By Burl Burlingame

groundbreaking planning process, but we

didn't get the future we planned on

Star-Bulletin

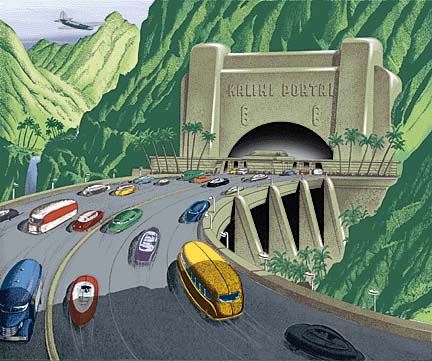

In 1946, to celebrate the end of the war, Hawaiian Electric commissioned a series of 12 advertisements that speculated about the "Honolulu of Tomorrow." Some of those predictions: FUTURE TENSE

On target: A gigantic airport, a grand state capitol building, windward Oahu turned into a suburb, a downtown auditorium, families living in apartments, a shell-shaped bandstand in Kapiolani park, a world-class aquarium.

False dreams: A modern yacht harbor, a neatly tended and planned Waikiki with a boardwalk, Hawaii Kai transformed into a giant park and "the world's greatest playground."

The Parkatorium fantasy: It was assumed everyone on Oahu would park in one gigantic building and take personal "gyro planes" to work. We're still waiting on that one.

Some of the predictions made in "Honolulu of Tomorrow" proved remarkably accurate, such as the illustration shown here, a highway tunnel for cars through the Koolaus. (Look familiar?)

IT seemed like a bright idea at the time, but unlike most that start out that way, this one looks even better in retrospect. Three decades ago, Hawaii legislators put together a task force to analyze the future. Scholars, legislators, planners, students and every stripe of citizen put their heads together to envision Hawaii in the year 2000.

This experiment in "anticipatory democracy" drew praise from around the world, and it is still considered the best event of its type ever produced. Hawaii was a role model. Ideas generated from the "Hawaii 2000" conference and subsequent seminars colored Hawaii legislation for years.

But that was then, and this is now. Legislators today don't think beyond the end of the session. The governor spends his days trying to retroactively balance the state's checkbook. The mayor's vision of the future smells like political hot air. Kids today don't believe in the future.

What happened?

Hawaii 2000 is almost upon us. Was the future all it was cracked up to be? We looked back on the original conference and talked to futurist James Dator, the University of Hawaii social scientist whose star was made at the time.

Hawaii 2000 happened by chance. Newspaper editor George Chaplin was invited to speak to the Hawaii Economic Association in late 1967. Groping for a topic, Chaplin was inspired by a magazine article called "Toward the Year 2000: Work in Progress," from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, chaired by sociologist Daniel Bell. Their goal, as Bell put it, was "an effort to indicate now the future consequences of present public-policy decisions, to anticipate future problems, and to begin the design of alternative solutions so that our society has more options and can make a moral choice, rather than be constrained, as is so often the case when problems descend upon us unnoticed and demand an immediate response."

In other words, planners should put as much thinking-ahead into public policy as architects do in designing buildings. The leaks, when they occur, shouldn't be a surprise. In another word, take the "duh!" out of planning.

Chaplin was completely torqued with the concept. Hawaii, he thought, with its new statehood, isolation, multi-ethnic population and small scale made it a perfect test lab. His talk, called "Plan Now for 21st Century Hawaii," got him an invitation to brainstorm with attorney Alvin Shim, then-Senate President John Hulten, House Speaker Tadao Beppu and Gov. John Burns. Others soon joined in.

This exchange of ideas led to some legislated funds, and on June 30, 1969 -- a few days before man walked on the moon -- Burns gave an executive order creating the Governor's Conference on the Year 2000. Chaplin chaired the advisory committee. Within the next year, 10 statewide task forces were created to study aspects of Hawaii's future, think tanks and mini-conferences took place, newspapers editorialized, high-school students were drafted to conduct learning workshops and the final conference took place in August 1970.

In 1971, a "permanent" Hawaii State Commission on the Year 2000 was created.In his opening remarks at the Hawaii 2000 conference, Dator said "the citizens of Hawaii and

the members of this committee have an unusually bright challenge before them; an opportunity no other officially organized group of people has, so far as I know. Many people in much of the rest of the world are either ignorant of or apathetic toward the necessity of planning their future. Many Americans seem to assume mistakenly that we can satisfactorily prepare for the future simply by believing and acting as we have in the past ..."

Man of the future

Dator joined the University of Hawaii in 1969, partly to teach political science and partly as cheerleader and coach of the Hawaii 2000 project. He's still at the University, still teaching students that the future is an inevitable reality; deal with it. He's still got the same haircut he had in 1969. Was this guy looking ahead, or what?"Why mess with perfection?" is how he explains the haircut. His interest in the future is more complicated.

Dator was "reared by three woman," and didn't know his father, and had no clue about his own ethnic origins. "I knew nothing of my own person; no clear ethnicity or family history. My name doesn't pop up in any other culture. I have no idea what kind of name Dator is. I had no way to look back. So I looked forward."

He became fascinated by macro-theories of society and history, Marx and Spengler and the rest, and the values that drive society. He wound up teaching in the College of Law and Politics of Rikkyo University in Tokyo, mulling over how best to teach future studies. He invented a curriculum in the subject at Virginia Polytechnic and fine-tuned it for three years before moving to Hawaii.

As he recalls it, it was "very liberating to be in Japan. I felt like I wanted to be Japanese. No matter what I did, to the Japanese it was both weird and OK. The Japanese were even less concerned about the present than Americans. I went there specifically to figure out why, as a society, Japan was able to modernize so quickly, to study their relationship between values, technology and culture.

"In almost every instance of social flexibility, I thought Japan was about 200 years ahead of other world cultures. It was quite a shock. I thought the United States was No. 1! By looking back at where they'd come from, I began to wonder what was next. That's when I began seriously thinking about future studies."

Oil crisis ends an era

Which started the scholar on the path to Hawaii 2000."The Hawaii 2000 sessions, as an exercise, are still the best any community has ever done," said Dator. "But it can also be seen as a failure, because only a few years later, in 1973, the oil crisis ended the future for Hawaii. It was the end of innovation in local government. It restructured the global economy, and in my opinion, Hawaii never recovered."

"We learned a lot of things, and now that we're here, the world and society is different than what we imagined it would be like, and that's interesting too. The future is not predictable. We never thought the '80s would happen," said Dator, with a shiver.

Other predictions were plain wrong.

"For example, we thought people in general would be interested in the environment and ecology and pollution, and instead, their focus is almost entirely on the economy. It's surprising that at the present time, environmental issues aren't important at all. Even general concerns about the consequences of growth are stilled in the islands."

They also didn't foresee the Y2K problem or the collapse of communism.

"Trillions of dollars to stop communism -- we just spent it to death -- and there is no comparable attitude toward environmental issue. And the Y2K problem will happen, yes, with clockwork precision. It's a wonderful example of something that's been a long time coming, inexorably, but the really interesting thing is why people refuse to take it seriously. Anyone who has lived through a dock strike here should have a taste of what to expect. I expect people won't start hoarding until it's too late. Did you know that, in China, the CEOs of all major airlines are required to be flying on Jan. 1?"

In Hawaii 2000 retrospect, in terms of planning philosophies, "social engineering is completely discredited, and a lot of us came out of that background. We have a new respect for cycles of behavior, such as the return to fundamentalism -- not just religious, but economic and social. Who'd have guessed?"

Links to the past

The view is clearer looking back to the past."Future studies don't predict -- anymore. Studying history has become more important to understanding what will happen in times to come. And what will happen? Three things we're sure of: Things will stay the same. Or they will turn on another cycle. Or everything will be completely new.

"The future is a continuation of the past. That's why the study of history is so important. We can predict, for example, that the presidential system in this country inevitably results in gridlock. Since World War II, of 43 nations that copied the U.S. presidential system, all are now military dictatorships. But only one-third of nations that use the parliamentary system have become dictatorships."

Is there a model for what's happening now in Washington?

"It's similar to what happened when Franklin Delano Roosevelt reinvented the Democratic party, which is essentially the same party we have today. That was successful. But when Ronald Reagan reinvented the Republican party, he married together a coalition of global free marketers and fundamentalist zealots. Today, you wind up with a Republican party that is not only narrow-minded, it has no sense of boundaries. The party is tearing itself apart, and doesn't care."

The point is, said Dator, historians and futurists have plenty to talk about.

"It would probably be better if there was a new academic orientation called 'chronology' that combines the two. Because neither history or future studies are rigorously scientific. There is no empirical data.

"It seems these days that what is important is not what's true about the past, but what we believe is true. What we allow ourselves to do in the future is largely shaped by our beliefs about the past. That's not the same as learning hard data. So, what we study isn't the future, but rather, we study our ideas about the future. Our culture programs our beliefs for us; our laws, our morals, our social structure. It's hard to imagine anything different, because we're not encouraged to imagine."

The biggest change in the last decade -- and one predicted by Hawaii 2000 planners -- has been the explosion of information technology, particularly the Internet.

"We were absolutely right on. And we wanted Hawaii to become a hub of this new information society. But that's been an utter failure. We never did the things we could have done when we had the chance, when we had the momentum and the imagination. It was a failure to look ahead. We're still rated an 'F' -- the university still has no policy on information!"

"Biology and environment also shape us, and the Internet is like developing a sixth sense. If it changes our behavior and our consciousness, then we'll think differently.

Dator, one of the first civilians allowed to access the military ancestor of the Internet, doesn't generally read science fiction -- "Too slow! I prefer poetry and science journals!" -- but recommends Spider Robinson's three-volume "Mars" series, because it deals with the politicized establishment of a new society on the red planet. Dator's perception of students today is that they're "brighter, they write better and they're more aware, but they don't have much of a social conscience. That's interesting."Dator can't wait for 2000 to be over. "For a futurist, it's as bad as 1984 was. Horrible year. Thirty years ago, the year 2000 was a wonderful symbol. It's isn't now."

But even a futurist can be surprised by changes.

On a trip lately, Dator discovered that his name means "computer" in Swedish. "Everyone laughed when I said my name in Sweden," said Dator. "They thought I'd made it up. But who can plan for something like that?"

Click for online

calendars and events.