Students do better, trail mainland peers

Isle public schools improve on testing from two years ago, but only 20 percent of eighth-graders are proficient readers

STORY SUMMARY »

Despite gains by elementary and middle public school students, Hawaii remains ranked near the bottom nationally in reading and writing, according to test scores released yesterday.

Compared with results from two years ago, fourth- and eighth-graders in the state improved their scores in both reading and writing in the 2007 National Assessment of Education Progress.

Pointing to the higher marks, state education officials praised teachers and students for closing the score gap among their mainland counterparts.

"We are having an upward trend in the NAEP, which is good to see," said Robert McClelland, director of the Education Department's Systems Accountability Office. "And in some cases we have improved a little bit more than the national average."

But Hawaii students still have to cover a lot of ground.

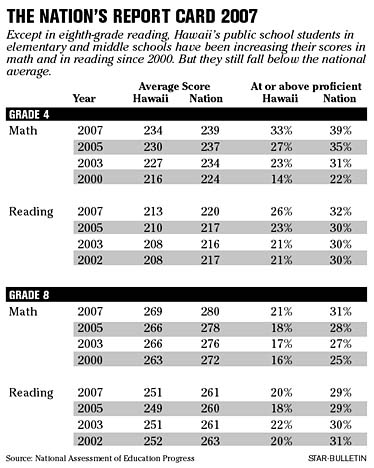

Just 20 percent of eighth-graders met proficiency in reading and 21 percent were proficient in math. Fourth-graders did better, with 26 percent proficient in reading and 33 percent in math.

The NAEP results showing across-the-board gains nationally will fuel the debate in Congress over whether the No Child Left Behind Law is working and should be reauthorized.

FULL STORY »

Hawaii students in public elementary schools are doing better in math and in reading than middle-schoolers, but test scores for the two groups remain below national averages, according to results released yesterday.

Fourth- and eighth-graders in the islands improved their marks in both subjects in the 2007 National Assessment of Education Progress from when the test was last given two years ago. About 15,000 Hawaii students took the national exam last winter.

The most troubling performance came in eighth-grade reading, with 20 percent, or just one out of five students, meeting proficiency, compared with the national average of 29 percent.

Although those students posted an average 251 points out of 500, a 1-point increase from 2005, the score dropped from 252 points five years ago and missed the national average by 10 points.

Only the District of Columbia and New Mexico had higher percentages of eighth-graders unable to solve reading problems at their grade level.

In math, 21 percent of Hawaii eighth-graders were proficient, shy of the national average of 31 percent.

But state education officials praised a strong showing by fourth-graders and said the overall upward trend in both groups indicates Hawaii public school students are slowly closing the score gap among their mainland counterparts.

Fourth-graders bettered their scores by four points in math and three points in reading. That raised the percentage of students meeting proficiency in math to 33 percent from 27 percent. In reading, 26 percent achieved proficiency, up from 23 percent two years ago.

Nationally, 39 percent of fourth-graders met proficiency in math and 32 percent in reading.

Schools Superintendent Pat Hamamoto called the accomplishments "a testament to the hard work of our teachers and students."

"Academic achievement is improving in Hawaii, and will continue to improve," she said.

The higher NAEP scores in Hawaii, although not as great, mirror progress in this year's Hawaii State Assessment, which saw 60 percent of students score proficient in reading and 38 percent in math, up from 47 percent and 27 percent respectively.

Known as the nation's report card, the national test provides the only uniform way to compare student progress in a variety of grades and subjects across the country. Its results, showing across-the-board gains nationally, came as Congress debates renewal of the No Child Left Behind Act.

President Bush welcomed the national report card, calling it proof that his signature education law is working.

Passed in 2001, the measure requires schools to meet steadily rising proficiency percentages, ending with all students being able to read and solve math problems at their grade levels by 2014.

Schools have been pushing hard to raise test scores and meet so-called adequate yearly progress to avoid penalties that culminate with a broad school reform known as "restructuring." It entails intervention by outside educational firms at state expense.

Teachers across the country have been complaining that the law puts too much emphasis on testing and punishing failing schools without providing funding to hire qualified teachers and reduce classroom size, said Evette Tampos, a counselor at Pahoa Elementary School who went to Washington, D.C., this month to push for revisions to the law.

"It really ends up all on the kids, poor things, being tested into oblivion," she said.

At Anuenue School, students were able to exit sanctions in reading this year, in part because of new computer programs for English instruction, said Principal Charles Naumu.

"One of the concerns, however, is the scores for meeting adequate yearly progress will increase this school year, so that will be a big challenge," he said.

The Associated Press contributed to this report