DENNIS ODA / DODA@STARBULLETIN.COM

Executive Assistant Lindsay Schoenecke, left, and Alexa Zen, community relations coordinator, work on the Baibala Hemolele project, which is updating the Hawaiian-language Bible and putting it online. Schoenecke calls up the 1837-1839 Bible used for reference.

|

|

New Hawaiian Bible is online

COPIES of Baibala Hemolele -- the Holy Bible -- are tucked on Hawaiian family bookshelves. But the Hawaiian-language version of Christian Scripture is not to be found in bookstores. It became a rare item in recent years after the American Bible Society decided not to crank out another edition to follow its 1994 reprint.

An earnest group of people in the Baibala Hemolele Project has worked since 2002 to restore the treasure. They expect to publish a hardcover New Testament next year, said project manager Jack Keppeler. They expect to have the complete Bible ready to roll off the presses by 2009.

But Keppeler said there's no need to wait: Their work-in-progress is viewable at baibala.org. The entire 66 books of the Protestant version of the Bible are available for scrutiny there.

The project launched by the nonprofit Partners in Development Foundation recently was awarded a $191,000 grant by the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. It has received more than $1 million in funding: $450,000 from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' Administration for Native Americans, $450,000 from the U.S. Department of Education under the Hawaiian Education Act and about $100,000 from private foundations.

Keppeler said it has also benefited from more than $200,000 worth of in-kind support from the Hawaii Conference of the United Church of Christ, the spiritual descendants of the New England missionaries who translated the book in the first place.

The first Christian ministers arrived in Hawaii in 1820. With the help of Hawaiians explaining the nuances of their language, eight ministers worked for 15 years to translate the Bible. They weren't just doing a new version of the King James Bible, the prevailing translation of their day. The missionaries translated from the original Hebrew of the Old Testament and the Greek used in early New Testament text.

Their scholarship stands, said Keppeler. "We're not translating it again, we are just re-spelling it."

Diacritical marks -- the pronunciation guides that the new generation of Hawaiian speakers considers part of the language -- are being added. Even with 21st-century technology, it is a "demanding, arduous task."

Phase 1 of the project was to have the existing text typed into computers, a job done in India.

Phase 2 was development of a software program by language specialists at the University of Waikato, New Zealand. The program inserts diacritical marks into the text -- but that's when the "arduous task" begins.

A team of editors is reviewing the pronunciation marks, okina by okina, to ensure accuracy. Hawaiian-language teacher Sarah Keahi is senior editor, and the team of interpreters includes Lawrence Keola Wong, a Kamehameha Schools instructor, and his wife, Annette Ipo Kamahele, who grew up on Niihau.

To illustrate how important it is to put the accent on the correct syllable, Keppeler used "malu" as an example. "It can mean shade or protection, but mispronounce it and it can mean spying, secrecy."

The project is broader than making the sacred book available to Christians.

"We have two audiences," said Helen Kaowili, assistant project manager. "One is people who want to use the Scriptures in the Hawaiian language." Calls and e-mails to the project reflect how people treasure having the Bible in their language. Kaowili said they've had requests from prisons, from a serviceman in Iraq seeking the Lord's Prayer, from a family wanting to engrave Tutu's favorite quotation on a gift bracelet.

"The other audience is language students," Kaowili said. "This translation gives us the Hawaiian language as it was heard in 1830 and as it was first recorded." As the daughter of the Rev. David Kaupu, she grew up speaking Hawaiian at home. She studied Hebrew and Greek at the International College and Graduate School in Nuuanu.

Keppeler said some Hawaiian-language education proponents did not support use of the Bible translation as a teaching resource. "It is a language resource, the first major document in the conversion of an oral tradition into a standardized written language. The establishment had not looked at the Bible, but it was the primary document in the Hawaiian language."

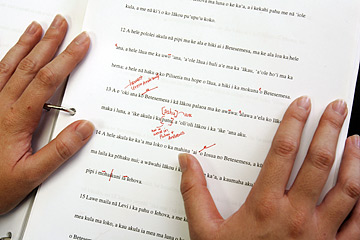

DENNIS ODA / DODA@STARBULLETIN.COM

This page has been worked on, showing the changes -- diacritical marks and edits -- marked in red.

|

|

Keppeler said the Rev. John Rawlins, a Baptist minister and former head of the International College and Graduate School in Nuuanu, compared the Bible translation to the Rosetta stone, which helped archaeologists translate Egyptian writing by comparing it with Greek text carved on the same stone.

"The myth that the missionaries botched the language has proven not to be true," Keppeler said.

The Gospel of Mark has been finished. It will be published within the next year in workbook format for use in language classes.

An oral recording of the Bible is in the works. The DVD will be sold with the print Bible.

Besides a simple printed Bible, they're talking about producing a showier version "to revive the custom of giving a Bible to a graduating senior," Keppeler said.

Keppeler and company have presented workshops about the project to churches and schools. They plan to take the show on the road to the West Coast to make a presentation at the Pacific School of Religion in Berkeley, Calif., present seminars for Hawaiian groups and tap other private foundations for further funding.

Keppeler is a member of Kaumakapili Church, where an adult Sunday School gathers each week to study the scriptural lesson of the day in the Hawaiian language. "The Bible passage is read in Hawaiian, and the congregation responds in Hawaiian," he said. "That's when the young people who have learned the language show their stuff."