GROVE FARM - A HOUSE DIVIDED

Litigation that divides family stems from sale clouded in suspicions

>> First of two parts

In January 2000, more than a dozen heirs of the 19th-century planter George N. Wilcox gathered in a movie theater on Kauai to discuss the future of Grove Farm Co. Inc., the sugar plantation that Wilcox had founded more than a century earlier.

At stake was nothing less than the future of the Wilcox family legacy: the possible end of a storied island family's connection to the historic company.

END OF AN ERA

For generations, Grove Farm Co. played a central role in the economic development of Kauai. The company's vast lands also were what one family member calls the "axis mundi" -- center of the world -- of the Wilcox family.

1864

George N. Wilcox acquires Grove Farm Plantation from Judge Herman Wedemann. Wilcox engineers the irrigation system necessary to bring water to cane fields.

1917-1930

Wilcox helps finance and construct a deep-water harbor at Nawiliwili.

1933

Wilcox dies at age 93; leaves shares of Grove Farm Co. Ltd. divided equally among his nieces and nephews.

1948

Grove Farm Co. acquires Koloa Sugar Co., giving Grove Farm a sugar mill.

1982

In a sign of its evolution from agriculture to real estate development, Grove Farm builds Kukui Grove shopping center.

Mid-1990s

Grove Farm ceases sugar cane production on east Kauai after more than 100 years.

November 2000

First lawsuit filed opposing the impending sale of Grove Farm.

December 2000

Grove Farm is sold to AOL co-founder Steve Case for $26 million.

November 2005

Additional lawsuits filed over the sale of the company.

|

Just months before, the company's chairman and chief executive, Hugh Klebahn, had written his cousins a sobering account: With the Kauai economy battered and Grove Farm's Kukui Grove shopping center partially vacant and damaged by termites, the company had barely enough cash to keep the lights on.

"THIS IS NOT BUSINESS AS USUAL," Klebahn wrote.

But a proposed solution, to sell the company to Klebahn's son-in-law, Scott Blum, had some of Klebahn's cousins nonplused.

Notes taken by a Grove Farm board member at the time document the concerns of several shareholders.

"Do we want to sell?" asked Patsy Wilcox Sheehan, the granddaughter of a former longtime Grove Farm president, Gaylord Parke Wilcox. The sentiment was shared by Suzy Hemmings, Sheehan's cousin from another branch of the family. Retired U.S. District Judge Martin Pence, the 95-year-old dean of Hawaii's federal bench who had married into the family, said he was "bewitched, bothered and bewildered" by the proposal. And Guy Combs, an outspoken cousin who was a certified public accountant, said the process was going "too fast" and that the Kauai economy was "turning around."

Less than a year later, Grove Farm Co. had been sold.

The buyer wasn't the chairman's son-in-law, but another son of an insider: Steve Case, the Internet billionaire whose father's law firm had represented Grove Farm for decades, and whose grandfather A. Hebard Case had spent decades working for the company. In just three generations, the Case family had gone from being merely employed by Grove Farm to owning it outright.

(Steve Case's father, Dan Case, is a director of Oahu Publications Inc., publisher of the Star-Bulletin.)

In the roughly five years since the deal was consummated, tensions have simmered over the sale. Now those tensions have reached a fever pitch, fueling litigation that has divided the family.

In lawsuits filed in state and federal court in Hawaii, former company shareholders, almost all of them heirs of G.N. Wilcox, claim that their cousins who were running the company misled them about Grove Farm's financial condition and fooled them into selling out needlessly.

COURTESY MOISES MADAYAG

The main house of Grove Farm on Kauai. The homestead, acquired by G.N. Wilcox in 1864, is now a private nonprofit museum, no longer owned by Grove Farm Co.

|

|

The defendants have said they had no choice but to sell; otherwise, the flailing company could have sunken into bankruptcy, leaving shareholders with nothing. Instead, Case emerged as a white knight -- a trusted expatriate kamaaina with family ties to the company and the lands it owned.

The matter is scheduled for trial in October.

Regardless of whether Grove Farm's board and management did anything wrong, documents produced as part of the lawsuits, as well as others obtained by the Star-Bulletin, detail some of the actions that the plaintiff cousins have seized on. The documents ultimately chronicle the end of an era: the last days of the Wilcox family's ties to the historic Grove Farm Plantation.

Among other things, Grove Farm's board allowed the same law firm -- then called Case Bigelow & Lombardi -- to represent both the company and Steve Case during talks. Furthermore, documents show that Grove Farm management refused to delay a shareholder vote for 10 days to give more time to a bidder that said he was willing to pay more than Case.

The documents also indicate the board failed to tell shareholders about a change in the company's financial situation that gave Grove Farm some breathing room when dealing with lenders.

And in perhaps the most bizarre twist, after shareholders asked for an official valuation of the company, management contracted the job out to a felon who was in prison on Oahu.

The defendants have attributed the dispute to sellers' remorse among shareholders who have seen Hawaii real estate values soar since they sold out. At the end of the day, "there were no real prospects for saving the Company," Corey Park, an attorney for the board, wrote in a 2002 letter to shareholders.

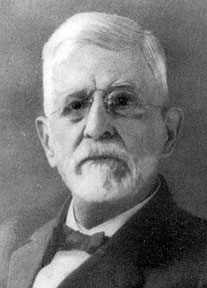

George Wilcox |

In any event, documents show how one group of Wilcox cousins -- including some who raised questions back in January 2000 -- aggressively questioned the campaign that another part of the family was mounting.

Underscoring the complex emotions the matter has triggered, some of the Wilcox cousins who most assertively questioned the sale have opted not to sue, citing the desire to maintain harmony.

"It would mean suing my brother-in-law, and I won't do that," said Barbara Fisher, widow of the late Charles Fisher and brother-in-law of Donn "Curly" Carswell, a Grove Farm director at the time of the sale. "No amount of money could repair the loving relationship I've had with my family."

David Carswell, the son of Curly Carswell and nephew of Fisher, summed up the situation in an e-mail sent to his cousins a couple of days after Christmas last year.

"I woke up to the sad thought that our Wilcox family is in the midst of a huge conflict, and on the verge of being torn apart," Carswell wrote. "It is hard for me to imagine that our close-knit family could be separated so suddenly, but unfortunately it is happening as I write this letter."

A proposal questioned

Whether or not Grove Farm truly was slouching inexorably toward bankruptcy in early 2000, its finances were anything but robust. Although the company had 22,000 acres of land on Kauai, it also was saddled with more than $60 million of debt. The year before, it had an operating loss of $5.3 million on revenue of $13.8 million. Klebahn described it to shareholders as "the classic 'land rich, cash poor' corporation."

In January 2000, the main questions about a proposed sale involved management's failure to obtain a valuation of the company before proposing to sell out to Klebahn's son-in-law for $21 million.

Among the more vocal skeptics was Pence, an antitrust expert who served for four decades on the federal bench after being confirmed as the first permanent federal judge in Hawaii after statehood. Also skeptical was Sheehan.

By January, Pence and Sheehan had been questioning Grove Farm management for months. After meeting with Pence and Sheehan at his office the previous November, Klebahn acknowledged to them that he knew of no appraisals that had ever been done of the company. He estimated Grove Farm to be worth about $12.8 million, or about $74.50 per share.

Steve Case |

In that context, the offer from Klebahn's son-in-law, which was $125 per share, was more than fair. But Pence and Sheehan were not convinced. In a letter dated Jan. 13, 2000, they reiterated their concerns.

"Where," they asked, "are the appraisals and the business valuations which are clearly necessary in order to understand what we own and what, therefore, is a fair price for our Company?"

In the end, the dissident camp prevailed. An election to enter a letter of intent with Klebahn's son-in-law carried just 66 percent of Grove Farm's shares; the company needed at least 75 percent.

A thief's appraisal

Obtaining an official value for the company to satisfy shareholders might have seemed a straightforward matter. But here things took a strange twist -- with the selection of a prisoner as Grove Farm's valuation consultant.

It was not Grove Farm's full board of directors that spearheaded the sale of the company, but a "special committee" of the board, which consisted of six members: Carswell, Pam Dorhman, Randy Moore, Robert Mullins, Wilcox Patterson and Bill Pratt.

From a short list that included such well-known firms as Kennedy-Wilson International and Deutsche Banc Alex. Brown, the committee chose Aspen Venture Group LLC, an obscure outfit run by Michael James Burns Jr., a smooth-talking businessman who at the time was in a work furlough program at Oahu Community Correctional Center, serving time for theft.

Burns farmed the work out to two Honolulu professionals -- appraiser John Candon and attorney Tom Foley -- who valued Grove Farm at somewhere between $86 and $98 per share, or about $15 million to $17 million. Bank of Hawaii executives later discovered what the bank called a substantial flaw: The tax-assessed land values used as a basis for the Aspen report were $17 million to $27 million short of the actual tax-assessed values, which according to Bank of Hawaii meant that the company was worth $138 to $150 per share.

Regardless, the special committee used the report to continue to promote the offer from the chairman's son-in-law, which was $125 per share.

Moore, a former president of Oahu's Kaneohe Ranch Co. who was the chairman of the special committee, cited the report when explaining to shareholders a reason to sell.

"We have a report from our financial advisor supportive of the perspective that Mr. Blum's offer is fair to the selling shareholders," he said.

But the dissident shareholders remained skeptical.

An advocate's passing

During the summer of 2000, Grove Farm's campaign to sell out entered a new phase, which began with a family loss.

On May 29, Martin Pence died at age 95, just months after he had retired from the bench. Pence's death marked the loss of a formidable advocate for family members questioning the sale. Pence had married into the family, and according to one of the other dissident shareholders, his role as an outsider gave him emotional distance that enabled him to challenge other family members.

Records show that up to the time of his death, Pence was fighting. Moore's diary entry for May 2, for instance, indicates that Pence, Sheehan and "six or seven" other board members had recently called the valuation consultant, Mike Burns, to ask him "who are you and what are your qualifications?"

Despite the loss of Pence as an advocate, other family members continued to challenge the push to sell.

STAR-BULLETIN FILE

In a sign of its evolution from agriculture to real estate development, Grove Farm builds Kukui Grove shopping center.

|

|

In June, company records show, Patsy Sheehan held a meeting at her home with several of her cousins, including shareholders and board members. The next month, shareholder-cousin Barbara Fisher called a meeting of shareholders at the offices of Pacific Century Trust, the asset management division of Bank of Hawaii, which managed several trust accounts holding more than 20,000 Grove Farm shares.

Before the meeting, in a July 5 letter to the special committee, Fisher asked what management was doing to make sure it got the best deal for shareholders. She also pointedly asked, "Are you or anyone... in management receiving any remuneration not fully disclosed for this transaction now or promised in the future?"

Despite such tough questions, the efforts to hold onto the company were beginning to seem futile.

"After every single meeting it was clear that we were not going to get anywhere," said one person who was at the Pacific Century meeting. "They were bound and determined to sell the company."

By early fall, the campaign would take another twist -- one that ultimately would intractably divide the family.

Property valuation choice settled on convict

Bank of Hawaii officials found error with the work performed by assessors

WHEN a special committee of the board of Grove Farm Co. Inc. created a short list of firms to conduct a valuation of the company, the list looked like the old children's game: Which one of these things is not like the others?

One of the companies was Deutsche Banc Alex. Brown, the multinational investment bank; a second was Kennedy Wilson Inc., a Beverly Hills-based real estate investment company with 500 employees; the third was Dole Capital LLC, a respected Honolulu investment banking firm.

The fourth on the short list was a little-known outfit called Aspen Venture Group LLC.

Aspen's relative obscurity alone might have given the committee pause. But what should have truly raised alarms was the background of Aspen's chief executive, Michael James Burns Jr.

According to Tommy Johnson, paroles and pardons administrator for the Hawaii Paroling Authority, at the time Grove Farm's committee selected Aspen, Burns was in prison at the Oahu Community Correctional Center serving a three-and-a-half year sentence for felony theft.

According to the prison warden's office, Burns was in a work furlough program from January 2000 until his release on parole in July, which explains how he could meet with clients and make a presentation in person to Grove Farm shareholders in May.

Former Grove Farm shareholders have seized on the hiring of Burns to support claims that the board failed to protect the interests of shareholders. But at least one of those who worked on the report said it is sound.

Tom Foley, a Honolulu real estate lawyer hired by Burns to do the valuation, said that he and appraisal specialist John Candon did the bulk of the work, and that the report is valid.

Foley acknowledged that Burns never paid Foley for the work Foley did. And Foley ultimately shared his concerns about Burns with Grove Farm director Randy Moore in an e-mail, saying "there are allegations from Monster Software, where Burns served as CEO, of fraud and embezzlement."

Gary Grimmer, a Honolulu lawyer who represents one of the defendants in the suits, said Burns' background was largely irrelevant because Candon did the bulk of the report. "Candon's a valuation expert that businesses in town use all the time," he said.

But the valuation appears to be flawed beyond its mere association with Burns, according to executives with Bank of Hawaii's asset management division. Bank of Hawaii's former Pacific Century Trust division in fact determined that Grove Farm was worth as much as 74 percent more than what Aspen reported.

In August 2000, documents show, Gil Farias Jr., an assistant vice president with Pacific Century, said that Grove Farms records showed the company's property to have a tax-assessed value of $156 million in 1999, the period covered by the report. Tax-assessed valuations for 2000 were $146 million, Farias said.

But Aspen used a tax-assessed value of just $129 million in its report as of December 1999.

Herb Wheatman, another Pacific Century executive, later wrote to Grove Farm's chairman and chief executive, Hugh Klebahn, saying Pacific Century could not reconcile the difference between Aspen's $129 million valuation and Grove Farm's records, which pegged the value at $146 million.

Wheatman said the discrepancy explained the difference between Aspen's valuation of $86-$98 a share and Pacific Century's valuation of $138-$150 a share. Still, Wheatman asked Klebahn for an explanation of the discrepancy.

"Otherwise," Wheatman wrote, "we must assume that the per share value opined in the Aspen report is erroneous."

Stafford Kiguchi, a spokesman for Bank of Hawaii, declined to comment.

Aspen's Foley acknowledged that the Aspen report could have been flawed if the consultants had not received complete information from Grove Farm.

"It's only as good as the information we got," Foley said. "But my recollection is we had volumes and volumes of information."

Lawyers for defendants in lawsuits arising from the deal point out that, regardless of the report, the buyer, Steve Case, ultimately paid $152 per share for the company. That was $2 per share more than the high end of Pacific Century's valuation.

Tomorrow: Steve Case steps in