|

column_name_here

column_author_here

|

HAWAII UNDERSEA RESEARCH LAB

When hydrothermal fluid cools, minerals precipitate out of solution, forming a dense cloud that looks like smoke.

|

|

Deep-sea life driven by chemical reactions

Life is chemistry, but it is more than mere chemistry. We do not yet know how to make life from chemicals, nor do we know how life arose from chemicals on the young Earth. But the deep-sea floor may hold secrets that will help us to solve the mystery.

In the first half of the 20th century, scientists thought the deep-sea floor was featureless and nearly devoid of life.

Creatures that were hauled up from the depths were scarce, and oceanographers believed that they subsisted on organic material that drifted down from above. No one imagined the richness and diversity of topography and biology that existed there.

Echo-sounding, an outgrowth of World War II sonar, began to reveal trenches six miles deep, mile-high seamounts and submarine canyons larger than the Grand Canyon. In the early 1960s, the first detailed maps of the sea floor showed a continuous range of mountains circling the Earth like the seams on a baseball.

Known as the mid-ocean ridge, this undersea mountain range is 80,000 miles long, greater than 1,000 miles wide and rises 8,000 feet or more from the surrounding sea floor, making it the largest single geologic feature on the planet.

Volcanism is common along the entire length of the mid-ocean ridge, but in most cases the volcanic activity does not produce distinct volcanoes. Instead, lava oozes sporadically through cracks and fissures along a narrow, shallow rift valley that follows the crest of the ridge.

Along the rift are hot springs called hydrothermal vents that form as hot water rises from within the ridge through cracks. Cold water flows inward and downward along the sides of the ridge to replace it, forming a convection cell within the fractured rock of the ridge.

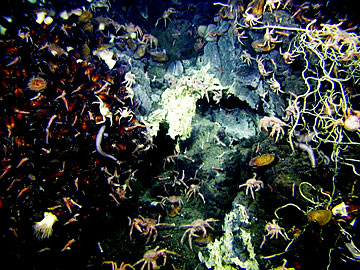

HAWAII UNDERSEA RESEARCH LAB

Crabs feast on snails, limpets and worms surrounding a hydrothermal vent.

|

|

As sea water descends through cracks and fissures into the ridge, it encounters partly molten rock beneath and heats up to as much as 750 degrees Fahrenheit. The pressure at this depth prevents the water from boiling, so it remains liquid even at these extreme temperatures.

Water at this temperature is extremely corrosive, and leaches metals and other elements from the surrounding basaltic rock. This hot, mineral-rich fluid is very buoyant, and rises rapidly back to the crest of the ridge, where it re-enters the ocean at hydrothermal vents.

There, it meets the surrounding ocean water, which is just above freezing temperature. The resulting mix can rise as a plume of warm water billowing hundreds of feet before it cools to the temperature of the surrounding water.

When the mineral-laden hydrothermal fluid cools, minerals precipitate out of solution, forming a dense cloud that looks like smoke, so some vents are referred to as "smokers."

Depending on the fluid's temperature and the dissolved minerals it contains, the smoky precipitate can look black or white. Black smokers emit hot water containing sulfides of iron and other metals, while white smoker fluid is cooler and contains dissolved compounds of barium, calcium and silicon.

The columns of dark metal sulfide particles often produce chimney-like structures around the vents. The chimneys are made out of sulfide minerals that precipitate out of the vent fluid and can grow to heights of 100 feet or more.

In addition to metallic sulfides, the hydrothermal fluids also contain significant amounts of hydrogen sulfide, which in the gaseous form is responsible for the distinctive smell of rotten eggs.

Hydrogen sulfide is a colorless, toxic, flammable gas that in ordinary circumstances is a product of bacteria breaking down organic matter in the absence of oxygen, such as in swamps and sewers.

The hydrogen sulfide and other chemicals that spew out of hydrothermal vents would be poisonous to most organisms. But tube worms and other animals flourish here, thanks to special adaptations and the relationship they have with the tiniest life at the vents: chemosynthetic bacteria.

Surface life on Earth is dependent upon photosynthesis, the process by which plants make energy from sunlight. Hydrothermal vents support a unique ecosystem in the absence of sunlight that draws energy from heat and chemicals rather than light.

Chemosynthesis is the process by which microbes extract energy from chemical reactions. The ecosystem of hydrothermal vents is driven by energy stored in the chemicals of the vent fluids. The chemosynthetic food web supports dense populations of uniquely adapted organisms, far from contact with photosynthetic life.

Chemosynthetic microbes are the producers, the first step in the food chain and the foundation for biological colonization of vents. They live on or below the sea floor, and within the bodies of other vent animals in symbiotic relationships.

In some places, a mat of chemosynthetic microbes covers the sea floor around vents. There, grazers such as snails, limpets and scale worms eat the mat, and predators such as crabs come to eat the grazers. Tube worms flourish in clumps, waving in the warm fluids.

An active hydrothermal vent is an isolated ecosystem of many vent species, all densely clustered around the vent, with a white microbial mat material covering the surrounding area.

Bacteria from hydrothermal vents are particularly interesting because they possess enzymes that can withstand high temperature and pressure, giving them many potential uses in industry. For example, some chemosynthetic bacteria can convert harmful chemicals to safer forms, making them candidates for cleaning up oil spills and hazardous waste.

The hydrothermal environment is so vast that it is now estimated there is more total biomass on Earth based on chemosynthesis than on photosynthesis.

Scientists are also curious about the deep sea's chemosynthetic ecosystem because it contains organisms that are among the oldest on Earth.

One ancient life form, Archaea, thrives in the deep-sea hydrothermal vent community. Many Archaea are called "extremophiles" because they can live in extreme environments where no other life forms can exist, such as in hot springs in Yellowstone Park, in extremely alkaline, acid or salty waters.

Archaea appear similar to bacteria, yet more than half of their genes are unlike anything else on the planet. They appear in the oldest rocks on earth, dating back 3.8 billion years, when conditions were inhospitable for other forms of life.

Rather than being oddities that have evolved to tolerate extreme conditions, Archaea may represent remnants of communities that dominated our planet when it was young, and from which all other life evolved.

Chemosynthetic Archaea and bacteria may be remnants of the oldest life forms on Earth, and may hold secrets to the beginnings of life from chemicals on the primitive Earth.

Their existence has given new boundaries for expectations of life elsewhere in the solar system.

Richard Brill picks up

where your high school science teacher left off. He is a professor of science

at Honolulu Community College, where he teaches earth and physical

science and investigates life and the universe.

He can be contacted by e-mail at

rickb@hcc.hawaii.edu