The costly coqui

Schofield Barracks deals with the

same problem facing the Big Island

amid real estate fears

As the sun sets over Schofield Barracks and dusk descends, exterminators break out a 100-gallon barrel, fill it with a lethal mix of citric acid and water, and start dousing the loudly shrieking amphibians that are menacing Hawaii's economy.

![]()

Coqui frogs currently only occupy about 10 acres straddling the Schofield Barracks Army base and a residential neighborhood nearby, but the tiny invaders have the potential to spread much farther and create the same headaches that homeowners and businesses on the Big Island and Maui have been dealing with for years.

Evidence of coqui-triggered economic disruption is so far mostly anecdotal, such as noisy mating calls scaring away prospective home buyers and coqui-infested plant nurseries shouldering additional expenses to rid their properties of frogs.

But as the frogs native to Puerto Rico enter their second decade of Hawaiian life, residents are increasingly noticing that coquis are not only hard on the ears, but also the bottom line.

"This is an invasive species of the worst kind," said state Rep. Clifton Tsuji, whose Big Island constituents must endure choruses of crying coquis coming from their back yards. "It's a species of mass destruction."

Sixty-two percent of Big Island real estate agents surveyed last year by University of Hawaii professor Arnold Hara said they had a part in deals affected in some way by the presence of coquis.

Nine of the 53 real estate agents in the report said they had handled cases in which home buyers backed out of contracts because the coquis were too loud. One said the presence of coquis had dragged down home prices in an entire subdivision.

Mac Lowson, president of the Hawaii Association of Realtors, said it is only a matter of time before the frogs start affecting real estate values.

"I would rather probably live next to a highway rather than live next to an area that has the coqui frogs. The coqui frog (sound) is a shrill shriek and then silence," Lowson said. "A highway is more of a continuous rumble, and there is something you can do with it."

Lowson, who can hear the coquis in certain areas of his town of Kapalua on Maui, said he might be particularly vulnerable to the coqui noise because he suffers from hyperacusis, a condition that makes him highly sensitive to sound.

But he said his wife, who does not have the ailment, feels the same way.

It is hard to imagine how a tiny, 2-inch frog could cause so much harm.

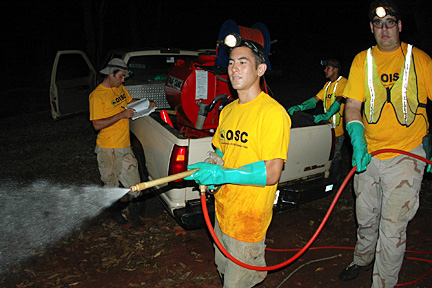

Field technicians with the Oahu Invasive Species Committee, Orion Stanbro, Daniel Tsukayama, Brian Caleda and vertebrate field supervisor for the OISC Dustin Lipiccolo spray chemicals in coqui frog-infested forest areas of Wahiawa.

But with no natural predators, the frogs have multiplied exponentially. Year-round temperate weather and open space also provide an ideal environment for them.

Brooks Kaiser, a University of Hawaii visiting scholar heading an economic impact study of coquis, said living next to a highest-density infestation could rival the experience of living next to an airport.

Residents of such a place, she hypothesized, could sustain damage to their hearing over the long term and suffer economic losses as a result.

Kaiser and her team expect to have some estimates on the economic damage of coquis in a few months after they compile data from Realtors and plant nurseries.

Trying to measure the effect the pesky frogs are having on the real estate market is particularly tricky because property values across Hawaii are currently soaring amid a housing boom.

On the east side of the Big Island, where the coqui infestations are the most serious, real estate prices surged between 24 percent and 36 percent in one year, said Reid Choate, a real estate appraiser specializing in the area.

Choate said the frogs have not affected property values -- yet. But he said he might find it necessary to mention the coquis in future appraisals if he hears them.

Lowson said coqui frogs might not seriously make their influence on the real estate market known until the market cools.

"The market's red hot. What's going to happen when the market isn't so red hot?" he said. "The houses that people are going to buy are those that don't have the coqui frogs around."

Eager to control and, if possible, eradicate the frogs, officials at the federal, state and county level are working together to battle the noisy amphibians, using concoctions of citric acid or hydrated lime to exterminate the noisy pests. The state allotted $300,000 to the counties this year, and officials say that helps.

But the task is daunting, especially on the Big Island where some 300 coqui populations have already colonized some 6,000 to 7,000 acres. Authorities there have already been forced into containment mode and have abandoned ambitions, for now at least, to eradicate the frogs.

Oahu's problems at Schofield Barracks pale in comparison.

Still, Scott Williamson, an invasive species biologist with the state Department of Land and Natural Resources, said authorities were "very worried" about how serious the coqui problem could become on the state's most populous island.

"Oahu's in the shape that Big Island was say eight, 10 years ago when they first started noticing them," said Williamson. "A few biologists said this is going to be a problem because they have the potential to breed anywhere almost in Hawaii. ... But nobody really paid any attention. Nobody thought a frog could be a problem."

E-mail to City Desk

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]