Boy monks perform chores inside the Punakha Dzong, a temple and fortress in Bhutan. The Asian country limits tourism and still clings to the old ways.

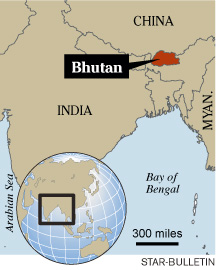

Asia’s Hidden Jewel

Pristine natural beauty makes

Bhutan a must-see destination

THIMPHU, Bhutan » In the Zone Bar on a Saturday night, movie star Cameron Diaz is celebrating a successful shoot with an MTV film crew by leading a rendition of Abba's "Dancing Queen" to a Thai karaoke video.

Diaz is here to film a segment of a tourist adventure series for the music television network on exotic and environmentally unique places.

Diaz is here to film a segment of a tourist adventure series for the music television network on exotic and environmentally unique places.

Bhutan is all that.

The country limits development; about 70 percent of the land is still forested. Tourism is also limited; less than 9,000 visas are issued each year, so those who get in feel privileged to pay a mandatory fee of at least $200 a day. The fee, which is $165 in the off-season, includes meals and adequate accommodations, even if the hot water doesn't always work.

Although most people have never heard of this Himalayan kingdom, the New York Times travel section calls Bhutan "the new must-see destination in southern Asia."

As word spreads, celebrities are becoming as easy to spot in the country as the takin, the strange-looking national animal of Bhutan that looks like a cross between a goat and a yak.

Demi Moore was here recently and, reportedly, so was former duchess of York Sarah Ferguson.

Ferguson stayed at the new Amankora resort in Paro, an ultra-luxurious boutique resort run by the Aman chain. Rooms can go for up to $1,000 a night, more than double the average annual wage in a country where most people are still subsistence farmers.

The Amankora is the first five-star hotel here. More are planned, although luxury is not what attracts most tourists here.

Two boys peek through a tent curtain at a celebration of the king's birthday in Punakha.

Around each bend of the notoriously winding roads is another spectacular vista -- snow- and cloud-covered mountain peaks soaring above rice terraces cut into steep hillsides; the deep green of both alpine and tropical forests; blue, green and white water rivers that cut past prayer flags and shrines that send Buddhist blessings to the world.

We camped in the Jigme Dorji National Park for a night, arriving just after dusk as rain began falling after a steep, uphill hike. Around a campfire, we sipped on ara, a local alcoholic brew, and feasted on Himalayan red rice and the national dish called ema datshi, a stew of chilies and cheese and sometimes local mushrooms or other vegetables.

A group of Layap men, nomadic yak herders who live in the mountains near the Tibetan border, stopped to meet with us on their way to the town of Punakha, where they sell yak meat, butter and cheese to trade for or buy rice and other staples.

Their leader invited us to come back next year and visit. The Laya village is about a three-day trek, but he said he'd send a yak so we could ride there.

Later, we joined the Layaps and local villagers in dancing and singing a traditional song in a circle around the campfire.

In the morning, the cloud cover lifted, revealing huge emerald mountains above a village where yaks still plow the rice fields.

The next day in Punakha was the king's birthday, a national holiday. In a field next to a river, schoolchildren wearing animal masks and colorful costumes performed dances, while red-robed monks, tourists and other spectators looked on. Two clowns, wearing masks with balloons tied to their heads, provided commentary and mocked some of the dancers.

Off to the side, local schools ran booths with dice games, where one could wager a small amount of money in hopes of a bigger payoff. The money raised goes to projects in the schools.

Musicians play traditional instruments to accompany dancers at a celebration of the king's birthday in Punakha as citizens and boy monks watch.

Most visits to Bhutan revolve around what tour operators call the "triangle" of Thimphu, Punakha and Paro, where the airport is located.

Above Paro is Bhutan's most famous and spectacular monastery, the Takshang Lhakang, also known as the "Tiger's Nest." Built on the side of a sheer cliff nearly 10,000 feet above sea level, it's reachable on a strenuous hike leading to stairs cut precariously into the mountain. Entry is only allowed with special permission, but there's a viewpoint before the stairs where one can photograph the monastery directly across a ravine.

Tiger's Nest is built on a spot where Guru Rimpoche, who established Buddhism in Bhutan, is said to have meditated in sacred cave after riding in on the back of a flying tiger.

Thimphu, the biggest city in Bhutan, is more like a small town. It's one of the few world capitols that does not have a streetlight. Instead, a police officer directs traffic by hand at the main intersection.

The country's only golf course (nine holes) is here, as well as all of the government ministries, the assembly and the king's offices and throne room, located in a tower in the Tashichho Dzong.

In Bhutan, citizens are required by law to wear the national dress, the kimono-like gho for men and a more feminine version called the kira for women. It's part of a mandate to try and preserve the Drupka culture here.

But at night, young people, many educated in the West or who watch fashion programs on television, wander between about a half-dozen bars, restaurants and a disco in their best western clothes.

Wooden fences mark a path between rice fields in the small village of Damji in the Jigme Dorji National Park.

There is a sense among those who have visited that they are seeing the place before it changes, while it's still unspoiled.

At the Zone Bar, a cell-phone network quickly spreads the word about the movie star visiting.

Cell phones were introduced to Bhutan only last year and are perhaps having more of an effect on the country than the introduction of television and Internet five years ago.

Locals, dressed in black, steal glances at Diaz, who is wearing a pink sweater and white ski pants. But they are polite and leave her party alone. There are no paparazzi here.

One man, who apparently helped with the shoot, introduces himself again to Diaz.

She is gracious with her time.

"I just love your country," she tells him. "It's so beautiful."

|

Hot chilies spice

Bhutanese food

Bhutanese food has been called the "world's worst cuisine."It's an exaggeration, but be warned. Bhutanese food is not for the spice sensitive.

Chilies, seen everywhere drying on rooftops and windows, are used as a vegetable. Children are fed chilies from a young age so they can take the heat.

The main dish here is ema datshi -- chilies in a cheese sauce. It's served for breakfast, lunch and dinner, sometimes with a red chili relish for those who really enjoy spicy food.

Ema datshi is served with locally grown Himalayan red rice, which cuts some of the spiciness.

As the economy grows, rice cookers are easily the best-selling appliance here. But as one local journalist told me, there's nothing like the taste of red rice cooked over a wood fire stove.

At the Bhutan Kitchen restaurant in Thimphu, we enjoyed a variety of traditional dishes including datshi mayno (fried cottage cheese), kewa paa (roasted potatoes), shakam tashi (dried beef with dried spinach) and nyetu ezey (roasted dry fish with chili powder).

But it is true that most food is prepared simply with not much spice other than chilies and salt, sometimes with a little garlic, onions or ginger.

Local yak meat, chicken or fish is available, along with an abundance of fresh produce. But it's usually prepared simply -- fried or sometimes with Chinese oyster sauce.

Still, aficionados say there's nothing like Bhutanese chilies. A diplomat said that while she was in Paris the best gift she ever received came from a Bhutan visitor who smuggled in some green chilies from home.

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]