|

Hawaii’s Chang goes deep

into the hip-hop years

to write his book

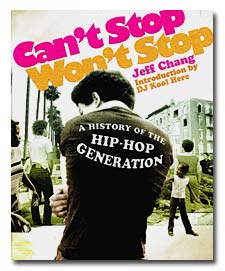

"Can't Stop Won't Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation," by Jeff Chang (St. Martin's Press), hardcover, $27.95

|

But Jeff Chang, nicknamed "Reggae" by his friends, had an epiphany in the early 1980s after seeing music videos like the Clash's "This Is Radio Clash" and Malcolm McLaren's "Buffalo Gals" on a then-fledgling cable USA Network, as well as listening to something new called hip-hop. Chang was hungry for more.

That's why he, his younger brother and friends headed to the Honolulu Academy of Arts theater in 1983 to watch a couple of documentaries on New York's street scene and its exciting street art, all exposed nerves and boisterous give-and-take.

The music was hip-hop, with beats and breaks mixed with a sure hand between two turntables and a mixer. The movement included break-dancing b-boys who contorted and flung their bodies around with creative abandon on impromptu mats of disassembled cardboard boxes. The lyrics were created by scruffy poets who furiously scribbled their rhymes in cluttered notebooks that reflected their hardscrabble lives.

The documentaries Chang and company saw showed hip-hop's South Bronx origins. The films were "Wild Style" and "Style Wars" -- and they were enough to start Chang on his journey.

He graduated from Iolani School in 1985 and moved to Northern California to further his education, jumped over to Brooklyn and is back in the Golden State again, with a well-received book, "Can't Stop Won't Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation," to his credit.

The book is his breakout, adding to Chang's already impressive résumé.

He's the first to admit his talents lie more in administration than as an artist. In a recent interview from a Philadelphia book tour stop, Chang said that at Iolani, "in my senior year, I did a graffiti art show, and got a lot of folks together. I admit I did my share of street art back then, but I wasn't very good in the art form. I knew how to get folks together, however, and tell a story. I'm still doing that today.

"It was kind of hard to predict that a kid from the suburbs of Honolulu would go on to do a history of the hip-hop generation and later hang out with the pioneers in Bronx. I didn't set out to do it, but in the 20 years since I graduated from Iolani, I got this book."

"CAN'T STOP WON'T STOP" is one man's explanation of how the label of "Hip-Hop Generation" -- those born between 1965 and 1984 -- is a more accurate sobriquet than mixing it in any X, Y or Z alphabet soup.

In the book's prelude, Chang writes, "My own feeling is that the idea of the Hip-Hop Generation brings together time and race, place and polyculturalism, hot beats and hybridity. It describes the turn from politics to culture, the process of entropy and reconstruction. It captures the collective hopes and nightmares, ambitions and failures of those who would otherwise be described as post-this or post-that."

Framing the book with the fiery 1970s demonstrations in the South Bronx and Kingston, Jamaica, on one end and the summer protests of 2000 at the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles at the other, Chang astutely interweaves musical and sociopolitical history that makes a compelling argument for hip-hop as a crucial positive cultural force.

With the release of the Sugarhill Gang's "Rapper's Delight" back in October 1979, Chang points out that the development of hip-hop in New York City was up in the air.

"One future offered a nicely trimmed path to folk art museums and cultural institutions that might nurture hip-hop in a small, safe world," Chang wrote. "The other was a bumpy, twisting road which might lead to cultural, economic and social significance but also to co-optation, backlash and censure.

"Hip-hop's downtown advocates, especially the older ones, understood the tensions. They favored authenticity over exploitation, and they vacillated between being protective of the culture and championing it."

But the declaration of local light Fab 5 Freddy to a journalist, in retrospect, was a telling point. "I didn't want to be a folk artist, I wanted to be a fine artist. I wanted to be a famous artist."

ALONG WITH the fame and hip-hop's growing influence on mainstream culture, Chang argues that -- with the subsequent rise of the South Africa anti-apartheid movement, evolving into a broader anti-racist movement on college campuses by the late 1980s -- rap would eclipse the other expressions of hip-hop culture in terms of importance.

Two groups that would signify that change would be Public Enemy and N.W.A, the former with a strong nationalist message and the other reveling in "the aesthetics of excess." It was the dichotomy of the street thug and the conscious Black.

In the last section of the book, Chang documents how that initial split in rap played out. The uncalled-for beating of black man Rodney King and his flawed trial in 1992 led to the L.A. riots, leading outspoken rappers like Sister Souljah and Ice T to confront the Clinton administration and police forces across the country.

And as the hip-hop nation's cultural influences grew in NYC, it became part of the selling of an urban lifestyle in the form of fashionable shoe and clothing companies.

Still, Chang says that political activism is an important aspect of the maturing of the hip-hop generation.

National critical response has generally been favorable to "Can't Stop Won't Stop." Entertainment Weekly said it strikes "a fine balance between journalistic flair and academic gravitas." "One of the most urgent and passionate histories of popular music ever written," opined the august New Yorker.

One common criticism of the book was expressed by Nick Marino of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, who wrote that "Chang's reporting is so heavy and his cultural history so exhaustive that the reader wishes he would provide some balance by unleashing his inner music critic." (Chang is a frequent contributor to the San Francisco Bay Guardian, the Village Voice, Vibe, URB and Spin.)

Marino also points out that while "(Chang is) all over the Rodney King riots, (he's) barely heard on the subjects of Run-DMC, Tupac Shakur and the Notorious B.I.G., three artists who raised the stakes for artists and listeners alike."

HIP-HOP HAS always been Chang's solace, dating to his student days at the University of California at Davis, where he also worked for the state government in Sacramento.

"Even though I worked for a progressive legislator as John Vasconcellos, it was pretty brutal work and uninspiring, especially during the last California budget crisis. My means of escape was deejaying at KDVS, the Davis radio station, and hooking up with DJ Shadow, Chief Xcel and Lyrics Born.

"We started SoulSides in '92, a creative outlet that at the beginning was just a side thing. It wasn't a full-time job, so I went back to academia and got my master's in Asian-American studies at (UCLA), where actually a lot of my research was on race relations in Hawaii.

"I taught a few classes, one specific on Hawaii, and it seemed I was going to continue on this academia track."

But he ended that ride to go full time with SoulSides in '95, which by then was getting national attention due to the superiority of its acts, like Shadow and Blackalicious.

"We were courted by a few major labels and thought it could be a viable option. A couple of years later, we released a couple more records. But the financial viability of the label changed, and people's interest changed as well. It was tough to stay alternative-independent by '97, difficult because the distribution companies we worked with went under."

As Chang's tenure with SoulSides ended (the label has continued as Quannum Projects), "I basically moved (to New York) to write again."

He started working on his book later that year, while working as political editor for hip-hop impresario Russell Simmons' now-defunct venture 360hiphop.com.

By then, Chang said, "I felt I learned a lot, and I still wanted to make a contribution. I definitely was interested to continue, and was beginning to understand that hip-hop culture was not just for us, but had become the big idea of our generation, like civil rights for the previous generation.

"So I started working and toying around with the idea of the book, which started out as originally an argument with Ice Cube's 'Death Certificate' album, and specifically the track 'Black Korea.'" (Cube's song criticizes Korean shop owners who set up in predominantly black neighborhoods in SoCal but generally didn't give back to their communities.)

"I actually interviewed Cube five to six years ago when 360hiphop.com was still around, and when we met in person, it was all good. There's always been a thing with hip-hop that if you disagree with something, there was always the response aspect to it. I responded to 'Black Korea' (because sometimes) art should be provocative and take you out of your comfort zone.

"Even after I met Cube, I didn't change my mind. I still vehemently disagree with a lot of the track. But what started as a conversation, just that one chapter in the book, means the most to me. There was so much emotion in writing that particular chapter."

FOR A BRIEF time, Chang's work for Simmons was his dream job, trying to bring hip-hop and politics together. He also met with the music's pioneers, like DJ Kool Herc, who would later write his book's introduction.

"I appreciated the work that went into the beginning of the music," Chang said. "I was also there covering the police brutality protests of that time, and the rise of hip-hop activism. So, even though I was later laid off from 360hiphop, I got a book out of it.

"My time with 360hiphop was during a year that Russell himself was dealing with politics straight up. I remember briefing him for his appearance on 'Hardball with Chris Matthews.' Overall, it was an amazing thing to see how my generation was trying to leverage power. It was a gratifying experience to also get involved last year with the National Hip-Hop Political Convention and League of Young Voters, and to try to get a progressive political agenda in hip-hop."

On his recent swing through the U.S. Midwest and east, he also met New York Times reporter Monica Davey, who used him as a source for her article on how some military service members in Iraq are creating raps during their time overseas.

"There's a lot of stuff already on the war, from rappers like Lateef, Mr. Lif, Sage Francis, to more commercial records like Eminem's "Mosh" and Jadakiss's "Why?" Hip-hop is already commenting on the war, but people are slow to see that. There's a lot of noise out there, club stuff, this-n-that, fun stuff, it's def out there.

"We're seeing music on the war more and more over the last two years," Chang said, "the voices of soldiers on the front line. And rap is such a portable form. You don't need a guitar, just pen, paper and a beat. It's immediate, just what's happening on the street and local level. ... I wouldn't be surprised if Iraqi rap came through in the next couple of months."

CHANG FINISHES his national book tour this month back in California, happy to be back home in Berkeley with his wife, Lourdes, and their two young sons.

"It's been amazing," he said of the experience. "It's been out since Feb. 11, and some days, it's been an out-of-body experience. ... The stuff that's been the most interesting is that people come up to me and say, 'Well, you didn't include my city or this story.' There hasn't been a straight-up def history of what's gone down. I'm just one guy in a movement of millions of people.

"The book was originally going to be around 500 pages long, and it came up 700. I tell them, 'You have to help get your story out there.' I've met a lot of people since the initial interviews, so I may include some of them for an updated edition.

"And I've always appreciated my experiences while in Brooklyn, and especially those in the Bronx. Those people were very patient with me.

"Look, man, I'm a kid who grew up in Honolulu, so what do I know? I'm humble; I wasn't there for the creation. But with this book, I'm trying to tell people that the argument that this generation gap has cohered into bad public policy is not true.

"It's not just hip-hop music that's a cancer on the culture. I'm addressing why there's such a huge gap between the baby boomer and hip-hop gen, and how we can fix it."

www.cantstopwontstop.com

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]