|

In a Nation of Fear

A new book about an old injustice

raises questions about wartime practices

|

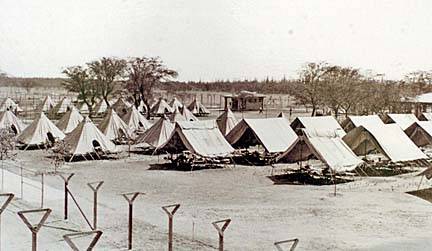

Question: Were all the camps the same?

Answer: "Assembly Centers" were temporary sites used to hold Americans of Japanese ancestry in 1942 until permanent centers could be built, called "Relocation Camps." Some sites, like Manzanar in California, were both.

Two agencies were in charge of relocation, one military and one civilian. The "Wartime Civil Control Administration," or WCCA, which supervised removal of the evacuees, fell under the War Department's Western Defense Command. The "War Relocation Authority," or WRA, was a civilian administration that supervised evacuees once they were relocated.

Smaller "Justice Department Internment Camps" were used to house AJA community and religious leaders, but also to hold more than 2,000 Japanese moved from Latin American countries, mostly Peru. About half of these were deported to Japan at war's end. About 300 of these Japanese Latins fought deportation in the courts, won and were allowed to settle in New Jersey.

Most camps were constructed on Native American tribal properties, for which the tribes were not compensated.

Q: How many AJAs were moved from their homes?

A: If all the evacuees had been gathered in one place, it would have been one of the most populous cities in the United States. In the course of the war, 120,313 people were under WRA control, of which 90,491 were transferred from assembly centers, 17,491 taken directly from their homes, 5,918 were born in the camps, 1,735 were transferred from Immigration and Naturalization Service internment camps, 1,579 were sent from assembly centers to work farms, 1,275 were transferred from penal and medical institutions and 1,118 were from Hawaii. Another 219 were non-Japanese spouses.

When the camps were shut down, 54,127 returned to the West Coast, 52,798 decided to stay in the nation's interior, 4,724 were deported to Japan; 3,121 were sent to Immigration internment camps, 2,355 joined the armed forces, 1,862 died during imprisonment, 1,322 were sent to prisons, mental or health institutions, and four simply vanished.

Q: Weren't AJAs in the camps prisoners of war?

A: Although the relocation camps cannot be compared to the Nazi death camps, or the deadly civilian camps operated by Imperial Japan, it was no vacation idyll for families held there against their will. They were deliberately held a long way from anywhere, penned in and watched by guards, no matter how friendly or sympathetic.

Real prisoners of war had more rights, thanks to the Geneva Convention (an agreement not followed by Japan during wartime). AJAs in the WRA camps were officially called "evacuees" or "segregees," never "internees" or "prisoners." Only the enemy aliens in the Justice Department camps rated that distinction.

Q: What's the difference -- internment or relocation?

A: It's a strict legal standard that is often garbled. Internment is involuntary. The Justice Department's camps for enemy aliens were of comparatively high security, while AJAs in the WRA camps were free to leave -- as long as they stayed away from the coasts. About half chose this option during the war. Fewer than 10,000 internees of Japanese citizenry were imprisoned in the United States under the Alien Enemy Act -- out of 29,055 interned -- and the other internees were of German and Italian ancestry, plus another 5,620 AJAs of dual citizenship who renounced their American passports and requested repatriation to Japan. There were apparently no internees held in the United States from the other six Axis powers, which included Finland and Thailand.

Ironically, about half of the aliens promptly arrested on Dec. 7, 1941, by the FBI were Germans or Italians -- countries with which the U.S. was not yet at war.

Q: Wasn't military service a way out of the camps?

A: The heroic exploits of the nisei soldiers of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and 100th Battalion are now part of American lore. More than 2,000 chose this option and helped free Europe from fascist rule. However, the nisei units were strictly segregated -- like black units -- and once battalion strength was achieved, it wasn't that easy to sign up. On the other hand, many AJAs of draft age, bitter about being relocated, refused to serve.

Not as well known are the estimated 38,000 Japanese Americans who served in the Imperial Army or Navy during the war.

Q: What was the effect of Executive Order 9066?

A: Of all the official wartime proclamations, this is the most notorious. Legal precedent already existed for the seizure of enemy aliens. EO No. 9066, however, allowed military commanders, under the rubric of national security, to declare certain parts of the country as "exclusion zones," applicable to both citizens and non-citizens. Under this order, all those of Japanese ancestry, whether or not they were citizens, were required to evacuate the coasts, many in such haste that their businesses and properties suffered. The basis for legal challenges to wartime relocation rests on No. 9066's violation of core constitutional issues.

Only in Hawaii was martial law actually declared, and only a small percentage of Japanese were relocated, mostly enemy aliens and community leaders.

Q: Wasn't relocation completely racist?

A: "Racist" is an emotionally loaded term. Only Asians of Japanese ancestry were relocated in the United States, while others, such as Filipinos, Chinese and Koreans, were left alone. While Japanese were reviled in popular culture, Filipinos and Chinese were often celebrated, however patronizingly. Unless you believe the Japanese are a distinct racial group, it's probably more precise to view the relocation as "nationalist" or "ethno-centric."

|

Q: Why was Hawaii treated differently?

A: The usual answer is that Hawaii, under martial law and surrounded by water, already had its Japanese-American population under tight control. The conventional answer is that, with AJAs comprising a third of the population and making up the islands' middle class, moving them away would cause the economy to collapse. Civilian and military leaders in Hawaii, in fact, strenuously defended Japanese Americans as loyal citizens -- likely because they had a better grasp of local political realities than faraway bureaucrats.

Not often considered is the notion that Japanese Americans in Hawaii were simply different from those on the mainland. AJAs in Hawaii had a better sense of community pride and a stake in island affairs, however tenuous.

Military intelligence agents were also stumped by a survey taken in 1941. Many AJAs asked if they'd be loyal to the United States or Japan if war broke out replied, neither -- their loyalty was with Hawaii.

Q: Isn't it true that no Japanese Americans committed espionage or sabotage during World War II?

A: It is more accurate to say that no Japanese Americans were charged or found guilty of such crimes during the war. Those suspected were simply sent to internment -- not relocation -- camps. For example, in Hawaii, three Japanese Americans on Niihau aided a downed Imperial Navy aviator to the point where they attempted to kill some of their Hawaiian neighbors. One of the Japanese was killed in a struggle and the other two surrendered to authorities. (This "Niihau Incident" is considered the trigger that largely justified the relocation order.)

In another case, AJA Richard Kotoshirodo actively aided Japanese spies keeping track of ship movements in Pearl Harbor. Until martial law, however, watching ships from public property was not a crime. Another AJA was shot in Kaneohe when he fled after being discovered signaling a Japanese submarine.

Ironically, the only undercover spies arrested in Hawaii were German.

Q: Why did American authorities suspect Japanese American loyalty?

A: A large part was certainly ethnic prejudice. Another major factor was the decryption of Japanese secret codes -- dubbed MAGIC -- that hinted at a vast espionage conspiracy among Japanese Americans. This was because the Japanese government made the simple assumption that those of Japanese ancestry abroad would be loyal to the Emperor. This turned out to be incorrect, but that position by Imperial Japan cast suspicion on all Japanese Americans. Another factor was a complete misunderstanding of the Japanese intelligence apparatus. In the Western world at the time, military intelligence was very specific in nature. Japan, which less than a century before had been a feudal nation, was not only curious about every aspect of the outside world but also deliberately maintained nationalistic ties with Japanese males who moved overseas. (Interestingly, not with Japanese women.)

Every Japanese community had a number of "consular agents" or toritsuginin, often Buddhist or Shinto priests, who collected news, gossip and family updates from their neighbors and passed it on to Japanese officials. To Westerners, this looked like a spy network. The consular agents were among the first people suspected by the FBI when war was declared.

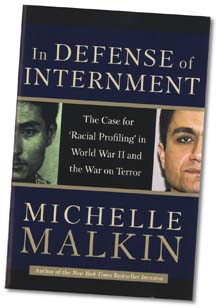

What if Malkin were a target for internment?

I can hardly wait to read Michelle Malkin's new book, "In Defense of Internment: The Case for 'Racial Profiling' in World War II and the War on Terror."Based on her Aug. 9 column in the Star-Bulletin, I assume she is going to argue that it was perfectly reasonable to round up more than 100,000 Japanese Americans during World War II, and therefore it is quite reasonable now to round up multitudes of Arab Americans and "other enemy aliens," as she so delicately puts it.

Let's think about who these "enemy aliens" might be today. First, we know that the Abu Sayyaf group in the Philippine is supposedly aligned with al-Qaida, so we should be highly suspicious of Filipino Americans. Second, isn't a hard-line, right-wing facade the perfect cover for someone engaged in subversive activities? You get my drift?

I'm sure Malkin will understand when someone knocks on her door one day and tells her that we have no choice but to ship her off to an internment camp. It's too bad she won't have any legal recourse, or even any way of knowing how long she will be detained, but I'm sure she won't have any hard feelings because she'll be happy in the knowledge that it's all being done in the interest of national security.

Honolulu

Profiling a valuable tool against terrorism

Racial profiling is justified when used appropriately, but the blanket interning of hundreds of thousands of people is wrong and imprecise. Just like lethal force, profiling is a valuable tool in the fight against crime and terrorism. We abhor killing, yet we know it is necessary to save life and liberty. The same is true for racial profiling.It would be nice if race wasn't used in any hurtful way, and it would be nice if ethnicity was not grounds for the limitation of freedoms, but that would be in a perfect world, something that does not exist.

It is politically correct to profess hatred for racists, but why do introductory conversations in Hawaii always seem to delve into ethnicity? And why did the Star-Bulletin identify Michelle Malkin as a "Filipino American?"

It is because race matters when it shouldn't. The fact is, some put ethnicity before things that really count: freedom, love, brotherhood, compassion and peace. Jews in America shape U.S. foreign policy to favor Israel on ethnic grounds. The NAACP and the Nation of Islam seek to further the cause of African Americans. Kamehameha Schools prohibits non-Hawaiians from attending.

Is this right? Some would say "yes" because they help to level the playing field by righting wrongs predicated on ethnic grounds.

If we really wish to stamp out racism, we would make race a non-issue for everyone. Until then, racial profiling should remain in the tool box of law enforcement agents, right along with lethal force and the impingement of civil rights.

Honolulu

Bad people come in all shapes and ethnicities

I'm an American, an American of Japanese ancestry, and I agree with Michelle Malkin on the internment issue. America struggles with the same problem after the attack on the United States by terrorists.America has progressed with new and amended laws based on experience from Dec. 7, 1941 and Sept. 11, 2001. America has also progressed by light years in the field of technology and information to remain at the front of the curve.

There are bad people in this world. Our challenge is to find ways to locate and terminate those bad people willing to kill humans anywhere in the world.

We must resolve our immigration issue by first closing our borders. At the same time, we must expedite entry into our country those who go through the application process and receive approval to enter.

I am a yonsei, fourth generation American. I am an infantry combat veteran of the Vietnam War. I am a board member of the Go For Broke Association. I have mainland relatives who were interned. None of my family members in Hawaii were interned. Two of my uncles served with the 442nd during World War II, and one served during the Korean War.

I have been asked to join the Japanese American Citizens League. My response then and today remains that the JACL is a racist organization.

Honolulu

Paper irresponsible in publishing Malkin

The Star-Bulletin frames Michelle Malkin's defense of World War II internment camps as an "emotional issue," putting the burden on the reader. I would argue that this is not an emotional issue so much as an ethical one, and that the burden is then on the Star-Bulletin.If Malkin has her facts wrong, which she does, and manipulates them in defense of the indefensible, why do you, as responsible editors, print it, even with the responsible explanation?

The Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, whose members included Sen. Edward Brooke and Arthur J. Goldberg, a former justice of the Supreme Court, concluded the following: "Executive Order 9066 was not justified by military necessity, and the decisions that followed from it -- exclusion, detention, the ending of detention and the ending of exclusion -- were not founded upon military considerations. The broad historical causes that shaped these decisions were race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership."

Next time around, perhaps the Star-Bulletin can find someone to write an op-ed in favor of slavery and against women's suffrage.

Kaneohe

Animosity borne of war lives for generations

All of these articles appeared in the Aug. 9 Star-Bulletin:

1. "Rethinking the wisdom of Japanese-American internment," a column by Michelle Malkin.Racial profiling during this time of our nation at war is an appropriate topic for discussion. But sometimes even if the rationale and logic for the patriotism of the Japanese Americans shortly after Pearl Harbor is made, one wonders if the same outrage would manifest itself when the nations (China vs. Japan or Philippines vs. Japan or Korea vs. Japan or Indonesia vs. Japan) still harbor ill will born of the conduct of the Japanese combatants during World War II at Nanking and Manila. Generations coming decades after the peace treaties are still at odds with each other. In this country, the old Japan-bashing of the 1980s could very well come back just as easily as the racial profiling of Muslims long after we depart from Iraq.

2. "Never again should the U.S. deny individual rights based on ethnicity," a rebuttal to Malkin's column by David Forman, a member of the Japanese American Citizens League.

3. "Soccer game turns political," by Jim Yardley, New York Times, about an Asian Cup soccer game between Japan and China at which fans hurled insults at one another that making reference to World War II.

Unless citizens who believe in civil and individual rights speak up and promote international understanding, national and internal ethnic divisions will persist as an out-growth of the resentments passed on from one generation to another in China, Philippines, Indonesia, Korea, Japan and the United States. As a son of a U.S. Army officer stationed in Manila after the end of the Japanese occupation and a Japanese-American Honolulu resident mother, and the spouse of a Visayan-Tagalog from Manila, and raised by a Japanese-Indonesian guardian in Yokohama, I know personally the difficulty of coming to terms with the conflicts of the World War II.

Former Reserve Unit Administrator

442nd Infantry, 100th Battalion

Honolulu

Racism motivated treatment of Japanese

It is a wonder that writers persist in stoking the embers of long past events as if they are adding more astute insight. Michelle Malkin's comments reveal that she is out of step by six decades on the internment issue, as she is unwilling to accept the role that racism played in the internment.Between January and March 1942, three persons of Japanese-American ethnicity were murdered in my home city of Stockton, Calif. No one was arrested and tried. Witnesses reported that all three assailants were Filipino. Also a number of Japanese-American homes were subjected to night-time shotgun attacks. No arrests were made, and there was only slight public concern. But to the Japanese-American community, this caused fears of a lynching hysteria.

These apprehensions and the lack of police concern led to the reluctant acceptance of relocation by the AJA community, which already had been subjected to:

1) Arrests of ethnic leaders on no changes.But favorable facts were not publicized:

2) Curfews.

3) Travel restrictions.

4) Curtailment of businesses by freezing of bank accounts.

5) Mandatory collection of "contrabands" -- cameras, weapons, ethnic literature, etc.

1) Richard Sakakida and Arthur Komori of Hawaii were sent to Manila in March 1941 to spy on the Japanese. After Pearl Harbor, they went to Corregidor to serve as Gen. Douglas MacArthur's linguists. When Corregidor was evacuated, Komori flew out of the island and escaped. Sakakida was captured, endured the Bataan Death March and suffered tortuous interrogation and abuse. "A Spy in their Midst" tells his story in full.Malkin needs to re-educate herself. She may write well, but being truthful and accurate are more important.

Lt. Col., U.S. Army, retired

Don't judge past acts by today's standards

Internment: Excesses are be expected during the mass anxiety of wartime, but Michelle Malkin makes a good case for the objective evidence that supported the internment decision. Public safety and victory, after all, remain the government's primary responsibility.A close family friend, a German immigrant, was incarcerated at Sand Island. We understood at the time that this misfortune was simply a reaction of caution and fear toward persons potentially sympathetic to the nations we were battling, Germany and Japan, and certainly not a "racist conspiracy."

We are too quick today to label all sorts of behavior as racist. We can never judge events in the past by today's standards. This is not to excuse internment, Salem witch trials, or the Spanish Inquisition, but simply to emphasize our need to understand the contemporary emotional climate that produced them.

Profiling: Of some 20 terrorist incidents in recent decades, every single one involved only Muslim males under age 35, who were mostly bearded and from Middle Eastern countries. Common sense would suggest scrutinizing everyone fitting this description more carefully than others. Even a child knows that someone who looks like a bad guy ought to be treated with caution!

Failure to employ profiling information in screenings is foolishly wasteful of resources and may be suicidal. At airports we go to great expense and inconvenience to perform a cursory inspection of everyone, including children, government employees, nuns and frequent travelers, while failing to scrutinize those who clearly meet the exact description of previous terrorists. All in the name of political correctness, and to avoid "hurt feelings."

Mililani

AJA internment was an 'un-American' act

I was taken aback to see such an article appear in print in the year 2004. The author's unconscionable intent is to clearly sell her book to a targeted market of presumed anti-AJA sentimentalists in America. This strikes me as nothing more than racism; mean-spirited and grossly un-American.Decades ago, President Reagan appointed a blue-ribbon commission on AJA internment, headed by former Supreme Court Justice A. Goldberg. This commission thoroughly investigated the events leading to the internment of AJAs. The president followed the commission's recommendations and sent out letters of apology with reparations to all surviving former AJA internees.

The report concluded that there was no legal, moral, or military justification for the WWII incarceration of AJAs. It happened they concluded because of "failed political leadership" (those in power failed to intervene in the injustices), and the hysteria of war which gave rise to the then-prevailing racism of distrust, suspicion, stereotyping and outright hostility toward Japanese and AJAs.

It's significance for today is that this is not repeated on our Muslim community with the conflict in the Middle East. If we have learned from our past, the American public will not let this happen, despite the attempts of crackpot revisionists such as Malkin, who surface from time to time.

Wahiawa

FDR had no choice but to lock up aliens

My mother and older siblings were devastated that our father was taken away from us and interned in a special camp in Santa Fe, N.M. I was 13.But in wartime, it was the only thing the United States could do to keep our country safe from inside infiltration or whatever could have happened to our safety and well-being.

If I were a leader of a nation as large as ours, I would be on the safest alert and do what is needed to be done, as President Roosevelt did -- round up Japanese aliens and keep them constrained from doing any more harm to our country as happened in Pearl Harbor, and not knowing which individual would be a threat to the United States.

This country is good, and the safest place on Earth, especially Hawaii. I wouldn't trade it for any other haven.

Pearl City