THE WWII INTERNMENTS

Friends Harry Urata, left, and Shozo Takahashi reminisced yesterday in Urata's music studio and sang "Moon over Sand Island," a song they sang during their internment.

‘A sad time ...

a challenging time’An exhibit and other events tell

the story of the Japanese Americans

in the isles who were detained

In March 1943, FBI agents arrived at the Honolulu Planning Mill in Kakaako where Shozo Takahashi worked as a woodworker.

CORRECTIONS

Monday, June 7, 2004Harry Urata taught Japanese at the University of Minnesota after he was released from Tule Lake Internment Camp. A story on Page A6 on June 2 incorrectly stated he taught English.

Friday, June 11, 2004Chojiro Kageura's last name was misspelled as Kaegeura in a Page A6 list of events June 2 that was related to the internment exhibit at the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii.

The Honolulu Star-Bulletin strives to make its news report fair and accurate. If you have a question or comment about news coverage, call Editor Frank Bridgewater at 529-4791 or email him at corrections@starbulletin.com.

Authorities issued Takahashi a warrant for his arrest, but allowed him to go home to pick up some of his belongings. His brother and wife dropped him off at the FBI office, where he was questioned.

Internment experiences

Here is a list of upcoming events related to the exhibit "Dark Clouds Over Paradise: The Hawaii Internees Story":June 19, 10-11:30 a.m.: Patricia Nomura will share a slide show about her experience when she was detained on the Big Island and taken to Jerome, Ark., and Gila River, Ariz.

June 26, 10-11:30 a.m.: The Taisho Boys (Harry Urata, Shozo Takahashi and Chojiro Kaegeura) will share their experience and how music played a part in their lives while they were detained in Hawaii.

July 3, 9 a.m.-noon: A panel will discuss the history of internment camps in Hawaii and on the mainland during World War II.

July 17, 12:30-2:30 p.m.: Book signing of Patsy Saiki's re-release of her book on internment, "Ganbare! An Example of Japanese Spirit."

July 22, 6-8 p.m.: Gail Okawa, an English professor at Youngstown State University in Ohio, will share her memories of her grandfather, who was detained in Hawaii.For more information on the exhibit, call the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii at 945-7633.

Takahashi was then taken to the immigration station, where he was photographed and fingerprinted. All the while, he wondered what he had done to be treated like a criminal.

But it would take the federal government 45 years to tell Takahashi why it detained him at the Honouliuli internment camp.

An exhibit will open Saturday at the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii, 2454 S. Beretania St., telling the story of Takahashi and other Japanese Americans who were detained at internment camps in Hawaii during World War II.

Takahashi and other former internees are expected to attend the opening from 1 to 3 p.m.

"Dark Clouds Over Paradise: The Hawaii Internees Story" will be displayed in the center's community gallery Tuesdays through Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. until July 31. Admission is free.

Many people are not familiar with the history of Japanese Americans who were held in internment camps in Hawaii, said Keiko Bonk, president and executive director of the Japanese Cultural Center.

The detained Japanese "had to ask themselves these serious questions of who they were and where they belong and how these things could be happening to them," Bonk said.

"It was quite a sad time, as well as a challenging time for the Japanese community," she said.

The Japanese have to speak and educate people about the injustices, Bonk added.

About 10,000 people in Hawaii were investigated shortly after the Pearl Harbor attack. Buddhist priests, ministers, Japanese school principals and community leaders were detained on the night of Dec. 7, 1941. Within two years, the FBI picked up a number of kibei -- Japanese Americans who moved to Japan during their youth to obtain an education and later returned to the United States. An estimated 1,250 Japanese Americans were detained in Hawaii during the war.

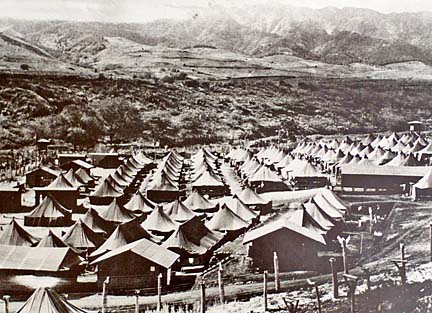

During World War II, Japanese Americans in Hawaii were held in internment camps such as this one on Sand Island.

Japanese Americans, along with some Germans and Italians, were held at internment camps on Maui, Kauai and the Big Island before they were transported to a Sand Island camp in May 1942. Officials later decided that detainees should be held inland to avoid the possibility of an attack.Detainees were taken to Honouliuli in Leeward Oahu on March 1, 1943. Takahashi said they were treated well.

"We all cooperate, no trouble," said Takahashi, whose wife, Yuriko, assisted as an interpreter.

He noted that detainees had the opportunity to do various jobs in the camp to earn coupons at 10 cents an hour. Takahashi said he and another man counted spoons before and after meals after they had heard that a detainee at Sand Island had sharpened a spoon into the shape of a knife in an attempt to commit suicide.

"If we miss some, gotta go all over," Takahashi said.

Takahashi said he took English classes, played his violin and attended Christian services on Sundays, when he prayed for the war to end.

At Honouliuli, Takahashi met Harry Urata, and the two became friends.

Yuriko Takahashi, who remained in Kaimuki, sent Takahashi a fingerprint of their first daughter, who was born in October 1943. In his excitement, Takahashi showed it to Urata. It was only then when Urata learned that Takahashi's wife was his former co-worker.

A year later, Takahashi went on a conditional release from Honouliuli. He was required to report to authorities once a month until he was let go in February 1945.

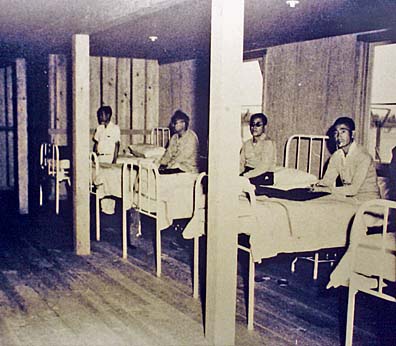

A hospital at the internment camp on Sand Island.

Takahashi, a kibei who was educated, underwent ROTC training and taught in Japan for 24 years before he returned to Hawaii, wrote to the government in 1988 and requested a copy of his internment records.A report cited in Takahashi's 1992 autobiography "An Autobiography of a Kibei-Nisei" stated he had dual citizenship and had "never attempted to be expatriated." It further stated that he lived in Japan for more than 20 years, where he attended school, received military training and taught students for four years. It also mentioned that he was a Japanese-language teacher in Honolulu for three years.

Takahashi said the authorities thought he was pro-Japanese.

Both Takahashi and Urata, who were born in Hawaii, had taught at the Waialae Japanese Language School at different times before the war started.

After the internment, Takahashi worked as a carpenter with his brother-in-law. He later returned to teaching at Japanese schools in Honolulu, had two more children and built a house for his family in Kaimuki, where he and his wife still live.

Takahashi, now 89, continues to take English classes once a week.

In March 1943, Urata was called to the principal's office at Mid-Pacific Institute, where two FBI officers were waiting.

The Honouliuli internment camp on Oahu is shown here.

The officers questioned Urata for two days before he was taken to the immigration station, where he was held for two weeks in a shack surrounded by a barbed-wire fence.He joined other Japanese Americans, many of them issei (first-generation Japanese), at Honouliuli. Urata read books in English and Japanese, played his guitar and sang songs to occupy his time. He also played baseball, practiced kendo and cut kiawe bushes outside the camp, which was also surrounded by a barbed-wire fence.

"You get to go out from the wire, fresh air," Urata said. While he was being held in Honouliuli, Urata said he often wondered why he was detained because he was an American citizen.

"Everytime I used to think like that inside the camp. I thought it was a mistake," Urata said.

Urata speculated he was held at the camp because he was a kibei who left for Japan when he was 6 and returned to Hawaii 13 years later.

Urata said he was among 69 men who were sent to the Tule Lake internment camp from Honouliuli in November 1944 after he described himself as being "hardheaded."

After he was released from Tule Lake, he taught English at the University of Minnesota for a couple of months before returning to Honolulu in December 1945, the year the war ended.

Urata opened a music studio in Palama, where he taught piano, guitar and voice lessons to generations of students. His studio moved to a few other locations before it settled in its current location in downtown Honolulu. He later married and continues to give voice lessons.

More than four decades later, Takahashi, Urata and thousands of former surviving internees each received a $20,000 reparation check and a letter of apology from the U.S. government for its injustice toward Japanese Americans during the war.

Urata, 85, said he is not bitter about his experience.

"They made mistakes," Urata said. "Everybody makes mistakes. But don't repeat that."

Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii: