Illegal practices involving foreign

moms complicate adoptions

here and nationwide

This was supposed to be a joyous month for Richard and Joyce Frost.

After trying unsuccessfully for years to have a child of their own, the New York couple paid $21,500 to adopt a Marshallese baby girl who was to be born in Hawaii this month.

The Frosts already had a name selected: Kaylia Grace.

But the couple never got to welcome Kaylia to their home. Instead of the joy of being new parents, they've felt nothing but frustration, sadness and anger in recent weeks.

The emotional turnabout came because of a botched adoption that is drawing more attention to the controversial practice of adoption agencies bringing pregnant Marshallese women to Hawaii to feed a national demand for babies.

A few weeks before Kaylia was born, the agency the Frosts were using contacted them to report that several birth mothers, including Kaylia's, had been "taken" from its Hawaii housing facility by a Kauai attorney.

The attorney, the agency told them, refused to release the women back to the agency.

When the Frosts contacted the lawyer, they were told they still could adopt Kaylia -- if they paid an estimated $22,500.

Already out $21,500 and with no baby to show for it, the Frosts were stunned. They refused to pay the extra money, which they said they didn't have anyway.

"It's morally wrong," Joyce Frost said. "It's evil. It just seems so unfair. Somebody has to be held responsible."

Just who is responsible is unclear.

Kathy Lahr, chief executive for Southern Adoption, the Mississippi-based agency the Frosts hired, didn't return several phone calls seeking comment.

The Mississippi Attorney General's Office confirmed that it is investigating Southern Adoption based on the Frost case and numerous other complaints lodged against the agency.

One of those cases involved David and Candace Chonka, an Oklahoma couple who said they paid Southern Adoptions $21,500 but, like the Frosts, have no baby to show for it.

The Chonkas also got the notice from Lahr that the Marshallese birth mother with whom they had been matched was kidnapped in Hawaii, he said. Unlike the Frosts, the Chonkas never contacted the Kauai attorney.

"We're out a lot of money," David Chonka said. "I don't expect to see a dime back."

Sue Perry, an official with the Mississippi Attorney General's Office, said the numerous complaints her office has received involve "concerns from people trying to adopt through Southern Adoption." She said she couldn't elaborate because of the pending investigation.

Linda Lach, the Kauai attorney whom Lahr accused of "taking" the birth mothers, disputed the allegations.

Lach, who has arranged Marshallese adoptions in the past, said people working with Southern Adoption contacted her office in mid-February to ask whether Lach could help a group of Marshallese birth mothers who were being improperly cared for on Oahu.

The mothers had been evicted from the Moanalua apartment complex where they were staying, had no money for food and shelter, and Southern Adoption had stopped sending them any funding, Lach said she was told.

Once Lach determined that the mothers were in distress, still were interested in adopting out their babies and wanted to work with her, she said she intervened. Nine birth mothers, including the one who had been matched to the Frosts, came under her care, she said.

"From my perspective, we rescued them," Lach said.

She acknowledged that she told three families who contacted her, including the Frosts, that they would have to pay her legal fees plus other costs to adopt the babies, even though they already had paid thousands of dollars to Southern Adoption.

"They're paying twice, there's no two ways about it," Lach said.

That problem, however, was created not by her but by Southern Adoption, according to Lach. "I certainly feel for (the families). I know this hurts. But I didn't do that."

Lach said two of the three families are going ahead with the adoptions. She wouldn't say how much they ended up paying, although, like with the Frosts, she said she offered to discount her usual legal fee.

Two other babies who were born after Lach intervened were placed with families she previously had worked with because no Southern Adoption clients by then had contacted her about those infants.

The baby who had been matched with the Frosts is now supposed to be placed with another former Southern Adoption client, according to Lach. That infant was born last week.

The Frost case likely will create more buzz about an adoption practice that already is drawing the attention of authorities in several states, plus federal agencies such as the FBI, the State Department and Bureau of Customs and Border Protection.

Aided by a U.S.-Marshall Islands compact agreement that allows Marshallese to travel to the United States without a visa, adoption agencies have been bringing pregnant women from that Western Pacific nation to Hawaii in the past few years, where they give birth and then turn over the babies to American families previously matched for adoptions.

The practice, according to critics, circumvents Marshallese law and tends to exploit the birth mothers, who generally don't understand that they are giving up their children for good -- a concept foreign to Marshallese culture.

Some critics also say the practice often involves adoption agencies committing fraud against the mothers, state and federal governments and health-care providers -- one reason law enforcement agencies are taking a closer look.

The Hawaii Attorney General's Office is investigating whether Medicaid fraud is involved.

Many of the Marshallese women, who usually don't speak English, are brought to Hawaii and enrolled in state-funded Medicaid, which covers their medical expenses. But in some cases, the adoption agency collects money for medical expenses from the adopting families while enrolling the mothers in Medicaid, raising the question of whether the families and state taxpayers are being double-billed.

That was one issue mentioned last week when U.S. Rep. Neil Abercrombie hosted a video conference to discuss ways to solve what he and others called a problem of human trafficking.

Lach, however, cautioned against tainting a whole industry by the unethical actions of a few. She said the problems associated with Marshallese adoptions have nothing to do with where the birth mothers are from.

"I think it's an unethical agency taking advantage of people who are desperate for a child," she said.

Kauai resident Kim Kennedy, on the national board of Ethica, an organization that advocates ethical practices in adoptions, said cases involving Marshallese women giving birth in the United States are unusual for two reasons: those adoptions are considered domestic even though the mothers are from a foreign country, and the adopting families pay for the birth mothers' medical expenses before the infants are placed with the families.

In international adoptions, the birth mother's expenses usually are paid by a government organization, orphanage or some other entity in the home country, not by the adopting family, Kennedy said.

If the family pays the expenses, "they're taking a big risk," she said, because the mother is free to change her mind about the adoption even after the baby is born.

The Frost case demonstrates another kind of risk: money for a birth mother's expenses can be paid up front to one organization, but the mother eventually ends up with another, rendering meaningless the initial payments.

That can happen even in cases involving U.S. birth mothers, industry officials say.

Although Frost and her husband had their hearts set on adopting Kaylia, she said they're trying to put that heartbreak behind them. They eventually plan to pursue another adoption through a different agency.

Frost said she hopes their awful experience of the past few weeks will result in positive changes to the system of adopting Marshallese babies.

"Maybe God was just using us as a tool to fix this thing," she said.

BACK TO TOP |

ASSOCIATED PRESS

Two-month-old Khith Sophal, one of Soum Savy's twin boys, is seen Feb. 1 in Laing Kout village, Kampong Cham province, Cambodia, 90 miles north of the capital Phnom Penh. Soum Savy was going to give her boys away but had second thoughts.

A Kauai woman faces

trial in a Cambodian

baby trafficking case

LAING KOUT, Cambodia >> The chief baby trader in this dirt-road village 90 miles from the capital waits at a pagoda to hear whether a neighbor will sell her 2-month-old twins to a family overseas.

"No?" Chea Kim says when told the desperate woman has changed her mind about giving up her children for as little as $20 each. "Why not?"

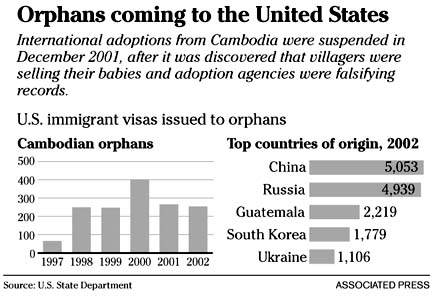

Although illegal baby sales may have slowed since the United States, France, the Netherlands and several other countries started suspending international adoptions from Cambodia two years ago, the practice persists in poverty-stricken villages like Laing Kout, according to an investigation by the Associated Press.

The director of one U.S. agency that appears to have benefited from Laing Kout's thriving baby trade is scheduled to be sentenced Friday in a case that made international headlines because the agency also handled the adoption of actress Angelina Jolie's son, Maddox. The agency director's sister, who lives on Kauai, is to be tried later this year.

There is no evidence that the actress did anything wrong or that the boy was not an orphan -- one of several hundred Cambodian children adopted by Americans each year until the ban, peaking at more than 400 in 2000.

In Chea Kim's case, an orphanage catering to international adoptions approached her five years ago and told her it was willing to pay up to $100 for newborns so she gave them her own 3-day-old daughter.

Later she regretted the decision, and when asked if she wanted to give another child said no. But that didn't stop her from persuading other mothers to sell their babies -- 18 in total -- claiming they had been abandoned and the birth parents were unknown.

Others in this poor village, most of whom earn less than $1 a day as contract laborers in rice and bean fields, recognized a good business opportunity when they saw one and also started bringing babies to the WOVA Cham Chao orphanage just outside Phnom Penh, the capital.

It was one of several used by Seattle International Adoptions, which placed at least 700 children in American homes before the U.S. ban in December 2001.

Following a U.S. investigation, the agency's doors were shut last year and its director, Lynn Devin, 50, and her sister, Lauryn Galindo of Hanalei, Kauai, 52, indicted on charges of conspiring to commit visa fraud.

Among the charges they faced were falsifying documents to make it look as if babies with parents were orphans, swapping at least one sick child with a healthy one in the middle of adoption procedures, and using the names of dead infants for the living.

Devin, who pleaded guilty to visa fraud and conspiracy to launder money, is to be sentenced Friday. Galindo, who pleaded innocent to the visa fraud allegations, is scheduled to go to trial in June.

Many of the women who gave up their newborns in Laing Kout were too poor to raise them, receiving as little as $20 for each child from intermediaries like Chea Kim. Some did so after being left by their husbands, out of spite or desperation, or in hope that adoptive parents, or the children, would send back money in years to come.

Complaints about baby sales and thefts have come to a near standstill since the United States and France, the two largest markets for Cambodian children, put a hold on adoptions, said Women's Affairs Minister Mu Sochua.

But some villagers are still trying to cash in.

WOVA Cham Chao stopped accepting babies a few years ago, but another orphanage opened in nearby Kandal province's Kein Svay district, allegedly run by a former employee, villagers from Laing Kout said.

Nop Phat, a farmer who has delivered five babies to the orphanage, rattles off the names of pregnant women in and around Laing Kout. He knows who is willing to sell a baby, and who is not. He had high hopes for Soum Savy, who had twins two months ago, but she changed her mind.

"At first I was going to give them away, because I was sick and had no milk," said Soum Savy, 40, emerging from a wooden house on stilts with the babies, one weighing just 4 pounds, his skeletal legs badly deformed.

"Now that I'm feeling better, I want to keep them," said Soum Savy, who has seven other children and no idea what she and her husband will do to feed them.

Chea Kim, waiting at a pagoda nearby, was disappointed by the news.

Cambodia, one of the poorest countries in the world, has no long tradition of civil society, and stories about selling children are not uncommon, whether for adoption, prostitution, or domestic service.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

Chea Kim, a chief baby trader, feeds a baby Feb. 1 in Laing Kout village, Kampong Cham province, Cambodia, 90 miles north of the capital Phnom Penh. Chea Kim has brought 18 babies to an orphanage near Cambodia's capital that caters to international adoptions. For each infant, Chea Kim was given $100, about half of which she gave to the birth mothers.

Decades of war have destroyed the social fabric, said Dr. Sotheara Chhim, deputy director of Transcultural Psycho-social Organization.

Little has been done in the years that followed to rebuild institutions that traditionally foster a sense of community or build values and trust.

Though it is impossible to say how widespread the problem is, even Cambodia's king has expressed concern, describing the adoption issue as "a complex but very sad one for me."

"Extreme poverty among a large number of our people ... has pushed a non-negligible number of parents to sell their children to rich foreigners," King Norodom Sihanouk, 81, wrote on his Web site in February.

Though some go to loving homes in America and Europe, and are given education, he said, "we are losing our dignity if we sell children."

Cambodian law limits adoptions to abandonment or the death of a child's parents. To get around this, adoption agencies and facilitators have claimed children were abandoned with birth mothers unknown.

There are many other loopholes in the system, and UNICEF is working with the government to draft a new adoption law.

Associated Press Writer Gene Johnson contributed to this report from Seattle.