[ MAUKA MAKAI ]

COURTESY OF NADINE KAM / NKAM@STARBULLETIN.COM

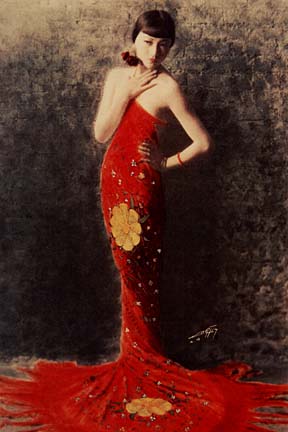

Anna May Wong had style that embodied boldness and sleek sophistication. According to author Graham Hodges, she could upstage anyone who shared the screen with her, including Douglas Fairbanks Jr. and Marlene Dietrich. She was a highly sought photographer's model and still inspires designers such as Colleen Quen and Maggie Norris.

A woman ahead

of her timeWong’s timeless beauty still glows

in a biography and film re-release

In today's celebrity-obsessed culture, Anna May Wong would no doubt be an instant international superstar. Magnetic, beautiful, talented, original and stylish, she was, unfortunately, born nearly 100 years before her time.

Anna May Wong was born Wong Liu Tsong at the edge of Los Angeles' Chinatown in 1905 to laundryman Wong Sam Sing and his wife, Lee Gon Toy. One of eight children, Wong managed to become a movie star, in spite of restrictions imposed by her culture and by American society awash with anti-Chinese sentiment.

Before the world would see such outspoken stars as Madonna, Marilyn Manson and Eminem, Wong was a progressive-minded provocateur who challenged Hollywood's use of actors in yellow-face and the Chinese exclusion laws that limited her career. This was at a time when Chinese were virtually invisible from American public life, isolated in major cities by Chinatown ghettoes.

"Anna May Wong: From Laundryman's Daughter to Hollywood Legend,"

by Graham Russell Gao Hodges

(Palgrave Press, hardcover,

304 pages, $27.95)

But even as she fought to forge a new dynamic image of Chinese in America, the roles she took -- villainess, vamp or victim -- were often perceived as demeaning to Chinese here and in the motherland. The result was political unpopularity leading to near obscurity today.

But Anna May Wong will have her revenge as she is celebrated with a new biography by Graham Russell Gao Hodges that coincides with the release of the British Film Institute's restoration of E.A. Dupont's 1929 silent film "Piccadilly," in which Wong plays a dancer at a London nightclub. The film plays through Tuesday at the Honolulu Academy of Arts' Doris Duke Theatre.

Hodges, a professor of history at Colgate University and the author of several books on New York City and African-American history, experienced Wong's allure firsthand during a 1999 trip to London, when a picture of her in a shop dealing in autographed photos stopped him in his tracks. Being a "collector type," he immediately plunked down 300 pounds for it, about $500.

His collecting didn't stop there.

"I started doing some research on the Internet, and I found out she was a very interesting person," he said during a phone interview. He added to his collection with photographs and postcards purchased on eBay, saying, "It became a little bit of an obsession."

HONOLULU ACADEMY OF ARTS

All her life, Anna May Wong played the exotic villainess, vamp or victim, when all she ever wanted was to play a modern American woman.

The obsession spilled over during a talk with an editor at Palgrave McMillan, a division of St. Martin's Press, and "Anna May Wong: From Laundryman's Daughter to Hollywood Legend" was born. Hodges was working on a book about New York taxi drivers but put that on hold to focus on Wong's story.

Hers might have been a typical movie-star biography, if not for the laws that governed her career, her travels and her love life.

"It brought me to a whole new world of Chinese-American history and a complex and fascinating person who had to deal with racism and early 20th-century attitudes toward the Chinese," Hodges said. As famous as Wong was -- a star in America, Europe and China -- she was subject to grueling immigration interviews before re-entering the country. The purpose of the interviews was to confirm one's identity and called for recitation of the names of one's family members, their birth dates, key anniversaries, addresses, occupations, etc.

There were also laws preventing relationships between Caucasians and people of Chinese descent. In Hollywood this meant that Wong could not kiss a white leading man, which prevented her from becoming a leading lady.

"It was one of the disappointments of her career as she was forced to play secondary roles while less talented white women were performing in yellow-face," Hodges said. So great was the acceptance of transforming Caucasian actors into "Asians" that Hodges notes in his book that Wong learned MGM considered her "too Chinese to play a Chinese" and instead cast Helen Hayes in "The Son-Daughter."

When the biggest roles for Asians came up in the casting of Pearl S. Buck's Pulitzer Prize-winning "The Good Earth," Caucasian Paul Muni was cast as the male lead, nixing Wong's chance to play the female lead. The part went to Louise Rainer, who won an Academy Award for her performance.

Even though Wong's real-life relationships were with older, accomplished Caucasian men, California laws against mixed marriages remained in effect until 1948. When one of her lovers conspired to marry her in Mexico, his Hollywood career was threatened. At times, Wong imagined marrying a Chinese man, but due to the mores of Chinese culture this was unlikely due to the taint of her career. If she did have such a relationship, she would likely have been forced to give up her career to play the obedient wife.

WONG WAS an early film fan. As a child she made laundry deliveries for her father and used her tip money to visit movie theaters at a time when the film industry was still in its infancy. She continued to seek the theater even though visits during school hours led to spankings with a bamboo stick from her father.

'Piccadilly'

Where: Doris Duke Theatre, Honolulu Academy of ArtsWhen: 4 p.m. today, 7:30 p.m. tomorrow and Tuesday

Tickets: $5 general, $3 for members

Call: 532-8768

The exotic world of Chinatown lured filmmakers to its streets, and Wong began begging for parts at age 9. She was dubbed "C.C.C." for "curious Chinese child."

Persistence paid off when she was given a part as an extra in 1919's "The Red Lantern," about a Eurasian woman who falls in love with an American missionary. Wong's first starring role was in 1921's "Bits of Life," in which she played the abused wife of Lon Chaney's character, Chin Gow.

In spite of her rapidly growing résumé, Wong learned that even in the fantasy world of film, there was no escaping the reality of racial prejudice. "The characters she was offered were often duplicitous, murderous, they were often raped," Hodges said. "She was dealing with things that other leading ladies didn't have to go through."

Whenever she tired of the parts offered in Hollywood, she headed for Europe, telling journalist Doris Mackie: "I was so tired of the parts I had to play. Why is it that the screen Chinese is always the villain? And so crude a villain -- murderous, treacherous, a snake in the grass."

In Europe she learned to speak German and French, and was welcomed as a star. She became, for people with limited exposure to Asians, the epitome of Asian womanhood. Women clamored to copy her haircut, tinted their faces to achieve the "Wong complexion" and donned coolie coats.

Off-screen, Wong traveled with an intellectual elite that included princes, playwrights, artists and photographers who clamored to work with her.

"She was in magazines all around the world, far out of proportion to the kinds of roles she had," Hodges said.

THE BRITISH FILM INSTITUTE

The British Film Institute has released a restored version of E.A. Dupont's 1929 silent film "Piccadilly," in which Wong plays a maid who is fired from her job at a London nightclub after this tabletop dance, only to be rehired as a dancer and charged with bringing exoticism and glamour to the once illustrious club.

"Notably, she was the one American star who spoke to the French people, more than Greta Garbo, Joan Crawford or Mary Pickford, the top American actresses of the time," Hodges said. "But she's the one who's now forgotten."

Wong's sophistication could not save her. Even as she railed against stereotypes, the roles she took as a matter of survival as a single woman marked her in China, where actresses were regarded as little better than prostitutes. China was emerging as a powerful nation concerned about the reputation of Chinese people around the world. Chinese nationalists were offended by Wong's portrayals, and while she was welcomed by the cultural elite in Shanghai and Beijing in 1936, politics was another matter. A journey to her ancestral village was abandoned when a crowd blocked her path, with someone yelling "Down with Huang Liu Tsong -- the stooge that disgraces China. Don't let her go ashore."

Wong nevertheless returned from China determined to be more Chinese than ever, paying close attention to the symbolism of her costumes and her portrayals. But she was caught in a Catch-22 situation in which her only options were to turn down roles, or to take them while trying to influence change from within the machine.

During World War II, with Japan at war with China, Wong worked for China relief agencies. In spite of her contributions, she was snubbed by Madame Chiang Kai-Shek during a propaganda tour of America from winter 1942 to spring 1943. According to Hodges, this was the start of a new mind-set that deemed Wong's portrayals embarrassing to China, and reflecting poorly on America's antiquated perceptions. Rather than blaming Hollywood for the stereotypes, Americans and Chinese found it easier to blame Wong. As a result, Hodges said, "Her memory has been washed away."

Unlike other stars with family to preserve their memory through commercial endeavors, Hodges said Wong's family is too shy to talk about her, though they provided some of the photos and documents reproduced in the book.

"Stars come and go -- some of my students don't know who Lauren Bacall is -- but that's just one part of it. (Wong's) just so politically unpopular because of a limited view that gets in the way of seeing her brilliance and artistry that goes way beyond the kind of roles she played.

"I think there's going to be a lot of rediscovery of her. Not a lot of actors in her day were doing a lot of writing and traveling. They would have liked to have access to intellectuals, but she had it. She was a major intellectual player, and there are not many actors like that."

IN SPITE OF his fondness for Wong, Hodges said he tried to be objective, pointing out flaws such as her penchant for alcohol. This led to liver problems, and while most of her immediate family lived into their 80s, she died at age 56, at home in Los Angeles in 1961. She was to have played Auntie Liang in "Flower Drum Song," and was replaced by Juanita Hall.

Hodges continues to be amazed by Wong's journey, especially in light of the fact that there has yet to be an Asian female star to eclipse her renown, given the many difficulties she endured and considering the changing times and attitudes.

Nancy Kwan, who followed Wong in the '60s, had a relatively brief career, and Hodges complains that Lucy Liu "has gotta get out of the roles she's playing," noting that she's been typecast as the martial artist/ spy/femme fatale.

"When is she going to get a role like Nicole Kidman gets two to three times a year?"

This indicates "the same struggles are there," Hodges said. As recently as 1990, Asian Americans were fighting to have the part of "Miss Saigon's" Engineer, assumed to be Vietnamese, filled by an Asian, rather than English actor Jonathan Pryce, who then became "Eurasian" to quell the controversy.

Although subsequent casts have featured Asians in the part, serious film roles for Asians are still limited to such foreign-made films as "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon." The only "blind" casting of an Asian-American woman in recent memory was Ming-Na Wen as Wesley Snipes's wife in 1997's "One Night Stand. Otherwise, Asians are cast by martial arts ability or to round out an ensemble, giving a cast a patina of diversity.

HAVING LIVED with the Wong project for about four years, including traveling to Shanghai, Hodges said he's ready to let her go since putting other projects on hold to finish his biography. Even so, Wong has a way of popping into his life.

On Monday morning, Hodges' wife found a photo of her that he had never seen. A friend of his also found a diary that spoke of a hotel at Santa Catalina Island, where the cast of "Peter Pan" had stayed while shooting the 1924 film. According to the diary, the cast, including a 19-year-old Anna May Wong, had stayed up all night shooting craps.

"I've done a lot of book projects, but I've never done anything like this before and it was great fun for me," Hodges said. "I had a fabulous time getting to know her."

Click for online

calendars and events.