CINDY ELLEN RUSSELL / CRUSSELL@STARBULLETIN.COM

Michael Rovner enjoys a ride aboard Dolly on the last day of his temporary job as a ranch hand at the Gunstock Ranch in Laie. Marvin Hunt, in the background, is the real cowboy, having worked at the 1 million-acre L.D. Smith Ranch in northwest Arizona for 18 years before moving here earlier this month.

Saying adios to the comforts

of the office and howdy

to life on a ranch

I wanted to be like Mitch Robbins.

He's the 40-year-old radio ad salesman played by Billy Crystal in the movie "City Slickers." Mitch was tired of his job and went to find his smile on a dude ranch.

I've worked in newspapers for nearly 25 years, 16 at the Star-Bulletin. I didn't want to quit my job, where I smile, sometimes. But I did want to try my hand at something totally different. I wanted to work. Really work. I wanted to give up the comforts of the office. My computer. My cushioned chair. The air conditioning.

Max Smith and his grandson, Ryan, provided me with that chance.

"I thought it would be good for you," Ryan said. "It would make you appreciate your job."

I headed out to the Gunstock Ranch, a 5,000-acre spread in Laie and Haleiwa, where I could get my hands dirty for three days. Three days of working in the sun. Good, clean living. Hard work. Man's work.

Goodbye, city life. Hello, rolling hills and the great outdoors.

Adios, deadlines and the stress that come with them. Howdy, cows and horses.

Max and Ryan welcomed me to their world with a smile.

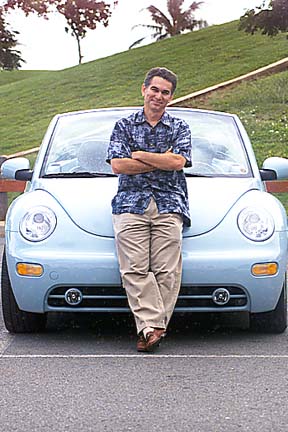

CINDY ELLEN RUSSELL / CRUSSELL@STARBULLETIN.COM

Rovner rests against the Volkswagen Beetle convertible that he traded in for three days for Dolly, a 1-horsepower, 18-year-old model that was a pleasure to ride.

Holy cow!

A cow is not a dog. I should have known that.This cow wandered from her pasture and had been tied to a tree by a taro farmer who didn't want her to trample his crops.

Max Smith, who runs the ranch, had gotten a call about a stray horse, which we found lazily grazing. His grandson, Ryan Smith, had thrown a rope over its head, and we were leading it home when -- from the back of a pickup -- we spotted the cow.

After taking Queenie home, Max dropped us off to rescue the cow. As soon as she spotted us, she struggled against the rope. The more she bucked, the more entangled she got. Mad cow disease had taken hold.

Ryan knew it. I didn't. He circled the critter from behind, keeping his distance.

I, on the other hand, slowly approached head on, my hand extended in a sign of friendship, as I would greet a dog. I figured the cow understood my intentions, since she stopped struggling. Spying me with her one good eye, the cow stood still, as if thinking, "He's gonna help me ... moo. I'll stop moo-ving now so he can untie me." But when I got within two feet of that 200-pound walking steak, she darted to her right, whipped around the tree and buried her forehead into my chest.

I staggered backward, nearly tripping over my own feet.

Ryan, too, was nearly knocked off his feet, but by a fit of laughter. He made his way back to me, teary-eyed. Seeing that I was not hurt -- my pride was hemorrhaging, unbeknownst to him -- he cut the rope, and the ungrateful beast lumbered toward her pasture.

I walked away, slightly stunned and thankful that cows don't have horns.

CINDY ELLEN RUSSELL / CRUSSELL@STARBULLETIN.COM

Rovner rakes up horse manure from a stall, a chore he did for only several minutes before being called away to help with the morning feeding of horses and cows. Luckily, he didn't have to do it again.

Oh Mickey, not so fine

"Mickey Mouse" is no longer a lovable Disney character. It's now a reference to someone who can't do good work."My grandpa said it first," Ryan said. "When workers do crappy work, my grandpa just laughs and says, 'Mickey Mouse.' Half the guys don't know what we're talking about."

I did. Ryan told me. But he didn't tell me that working the ranch was such hard work. I was surprised how much time I did not spend on a horse, and how much time I worked.

"When you do this kind of real hard work on a hot afternoon, and someone asks you how the office looks," Max said, "it might look pretty good."

My first test came in the form of 10 bales of hay. They reminded me of giant rolls of toilet paper, although each weighed several hundred pounds.

They were stacked on a trailer, ready to be delivered to several pastures. Seemed easy enough. Ryan and I would push them out the back and, presto, lunch was served.

The first two were easy, but the third was wedged above another bale, stuck between two metal poles that spanned the width of the trailer.

We pushed. We shoved. It didn't budge. Our efforts drew a crowd -- horses, some taking bites from the bales as if that would help.

Ryan decided we needed to lighten the load by peeling away several layers from that bale. He shredded from the top. I did the same from the bottom. Guess I didn't have much horse sense. I was showered in a "hay storm." The stuff got inside my shirt. In the creases of my neck. In my mouth. My pants. I found more in my ears that night.

Getting dirty -- really dirty -- is a big part of working a ranch. "It's just a normal day at work," Ryan said.

"It's got its benefits, though," he said, pointing to a bicep, "and you get a heck of a tan."

CINDY ELLEN RUSSELL / CRUSSELL@STARBULLETIN.COM

Rovner helps carry small stacks of hay and buckets of alfalfa cubes to feed some of the 60 horses and 200 cows on the ranch.

A heck of a workout

I'd never split a log, let alone one 20 feet long. Yet I had to help Ryan and Nielson DeBueno do it four times. Not just in half lengthwise, but into quarters with a wedge and sledgehammer. We later hauled the pieces to the mare pasture, where each was measured, cut and lifted into position along the fence posts. They were soaked in creosote, a preservative that, Max said, "stops termites. Stops anything."Nearly stopped me. Small droplets of that toxic waste got on my face and arms with each hammer strike, burning my skin. Washing it off provided some relief, but the stinging didn't go away for hours.

We had to string barbed wire to keep cows and horses from trampling nearby taro and ginger fields. Not just a few yards of the prickly stuff, but at least 100 yards, through a tangle of brush, trees and, at times, along a precarious slope above a dry river bed. Not just one strand -- they could jump that. Three strands.

Every morning at 7:30, Nielson and I filled 10 5-gallon buckets with alfalfa cubes to feed the horses and cows. We'd move from stall to stall on the doorless truck, sometimes performing "ranch acrobatics" -- a mild form of contortion -- to dump the cubes into feeding bins.

The alfalfa in no way resembled the stuff you and I sprinkle on sandwiches or salads. If thrown, it could break windows.

At one feeding, at least 10 horses from the adjacent pasture circled the truck, searching for bits of hay and alfalfa cubes to feed on. They were too big to shoo away, so I walked cautiously through them to get back to the truck. I was afraid I'd get trampled if I spooked them.

I was amazed by their size and their beautiful black eyes. I marveled at their massive, powerful muscles. I was impressed by their gentleness.

Back at the truck, I dropped my empty buckets in the bed and took my seat, grateful for this chance meeting.

Each morning, Ryan picked me up at 6:30 a.m. for the 45-minute ride from Kailua to Laie. Our day ended at about 5 p.m.

"I'm a true city slicker," Ryan said as we drove home one evening. He was raised in Salt Lake City and has worked at Gunstock every summer since he was 14. He's now 19.

"When I come out here, I'm a country machine," he said. "I'm full-on country and nobody (at home) knows. They have no clue. They have no clue that I'm a cowboy."

Well, I'm not. We're heading home. I'm beat. Exhausted. And I'm really dirty.

CINDY ELLEN RUSSELL / CRUSSELL@STARBULLETIN.COM

Rovner and Nielson DeBueno pry open a telephone pole that was used for a fence. They split it with sledgehammers and wedges.

Here's to Duchess

I saw the horse by the stables after a morning feeding. She was on her side, her breathing labored. "We found it in the pasture. We found it like this," Max said of Duchess, owned by James and Linda Todd, of Hauula. "We gave it some shots and encouraged it (to come to the stables) so we can watch it."I watched her for nearly 30 minutes before I had to leave to do my chores. She would rear her head and try to stand, only to fail. I tried to comfort her by petting her broad forehead. Max said she was suffering from a real bad stomachache. "There are many causes of colic, but the most common is food disturbance. We haven't had one for several years. But it's a common call for the veterinarian."

Dr. Manuel Himenes, of Kailua, drove up at about 1 p.m. and got her on her feet with a slap on her side. He listened to her heartbeat before fetching a flexible tube about 8 feet long from the mobile clinic in his pickup.

I winced as he guided 6 feet of hose through her left nostril and into her stomach. I gagged when he first pumped water, then mineral oil through the tube. Duchess took it better than I did, only sneezing a few times to try to expel the tube. The oil, Himenes said, would "stop the formation of gas and move whatever's in the stomach."

Then he slipped on a clear plastic glove as long as his arm, and slowly pushed his way up her okole. She just stood there, as if this happened all the time. Himenes felt around like someone searching for a set of keys in the dark. "Everything feels like it's in the right place," he said. "You just gotta watch her for now."

The Todds took her home, where their children "walked her all afternoon and evening," Linda said. "In the morning she was still standing, but she would not eat or drink anything."

Duchess died that day. "She had a three-minute seizure and she died," Linda said. "She was a wonderful horse."

I'm sure she was.

CINDY ELLEN RUSSELL / CRUSSELL@STARBULLETIN.COM

Horses gather around Michael Rovner as he sits on a bucket filled with grain used as bait to halter Satin. Ryan Smith wanted to ride Satin that morning at Gunstock Ranch. The horses try repeatedly to nudge Rovner off the bucket. Smith tries to halter Satin for nearly 30 minutes before giving up, but succeeds later that day.

Hello, Dolly

"My 6-year-old granddaughter rides her," Max said.Well, if Lori Ann could ride Dolly, surely I could. After all, Lori Ann's only 6 and Dolly's pregnant.

"Smokin' Joe got loose one night," Max said, "and Dolly was in the yard."

For the first time, I saddled a horse, and for the first time in about 30 years, I tentatively climbed aboard. With a gentle kick, we joined Max Smith, Brandi Puntin and Marvin and Linda Hunt.

We meandered through several pastures and worked our way through thick forests to a hilltop overlooking the ranch and the Laie coastline. Beautiful.

We kicked up small puffs of dust from the red-dirt trails that cut their way though fields of grass and shrubs. I gently bounced in the saddle as we made our way back. Those bounces turned into a series a rhythmic jolts when I spurred her to a trot.

The ride was smoother when Dolly galloped. Prompted by a slight kick to her sides, she took off. I was amazed that such a large animal could move so fast. I hung on, afraid but excited. Dolly dashed across the sand-covered arena and circled to do it again. I laughed when I pulled Dolly to a stop.

I now understood the joy of being a cowboy. At least, I think I did.

Yesterday: At 79 years of age, rancher Max Smith is still chasing and roping cattle.

I loved the freedom from the back of a horse. The thrill. The exhilaration. The simple joy of working the land and tending the animals.

I rode Dolly later that day. A trot around the arena before taking her back to the stable, where I took off her saddle and stowed it in the tack room. I showered her to remove the day's grit and in my own way said goodbye.

I'm going to miss her. I'm going to miss a lot about Gunstock Ranch. The feedings, the smells. The horses and cows dotting the hillside. Ryan. Max.

Strangely, I'm even going to miss splitting those polls and struggling to hoist them into position with Nielson, Ryan and Gerard "Tahiti" Teriitahi.

"You did good," Ryan says as he drove me home. "You did really good ... for a newspaper editor."

I'm glad. He didn't call me Mickey Mouse.

CINDY ELLEN RUSSELL / CRUSSELL@STARBULLETIN.COM

Rovner and Nielson DeBueno struggle to hold up a pole as Gerard "Tahiti" Teriitahi pounds a nail into the other side. Hearing Teriitahi repeatedly miss the nail elicits some chuckles.

CINDY ELLEN RUSSELL / CRUSSELL@STARBULLETIN.COM

Rovner laughs after enjoying a gallop on Dolly in the arena. It was his first ride in about 30 years.

CINDY ELLEN RUSSELL / CRUSSELL@STARBULLETIN.COM

Ryan Smith, at left, and Rovner strain to dislodge a bale of hay stuck on a trailer.

CINDY ELLEN RUSSELL / CRUSSELL@STARBULLETIN.COM

Rovner wipes away dirt and sweat.

Click for online

calendars and events.