[ WEEKEND ]

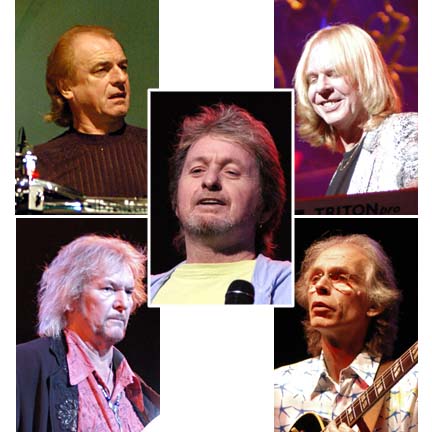

COURTESY OF YESWORLD 2003

Back to rock with the Honolulu Symphony are, clockwise from top left, Yes members Alan White, Rick Wakeman, Steve Howe, Chris Squire and Jon Anderson, center.

Positive

on rock

Jon Anderson, in his continual search for the meaning of life, is happy to share his thoughts.

CORRECTION

Tuesday, Oct. 21, 2003>> In a story on the group Yes in the Sept. 26 Weekend section, some information provided by lead singer Jon Anderson was read over the phone to the reporter, without giving attribution, from various articles that have appeared in the UK Guardian, the group's Web site and associated links.

The Honolulu Star-Bulletin strives to make its news report fair and accurate. If you have a question or comment about news coverage, call Editor Frank Bridgewater at 529-4791 or email him at fbridgewater@starbulletin.com.Anderson's no longer a wide-eyed hippie but the hardheaded leader of Yes, a band that has survived 35 years and is completing its umpteenth world tour, "Full Circle." The group performs with the Honolulu Symphony at 8 p.m. tomorrow at the Blaisdell Arena.

"The meaning of life would be this table," says Anderson, 59, who lives on the Central California coast with wife, Jane. "The coffee table is the world as we know it. There are mountains, valleys, animals and inter-dimensional energies that we don't know about.

Yes

Performs with the Honolulu SymphonyWhere: Blaisdell Arena

When: 8 p.m. tomorrow

Tickets: $45 to $65

Call: 792-2000

"Or maybe we do. Actually, I know a lot of people that do. Inter-dimensional energies are a very powerful thing."

Anderson is a rock star from the by-now alien 1970s era. He says things like "In the early '90s, a lovely little lady who lived on Pensacola Street in Honolulu came by and was able to ignite my third eye" with a deadly seriousness.

In a gentle, friendly tone, Anderson explains that he was once visited by angels in a Las Vegas hotel room. They told him to remember William Blake. "It was quite a very sobering experience," he says.

His personal philosophy -- "I say to my beautiful wife Jane, I wouldn't have met you if I hadn't gone through my whole life to get to you when we met" -- can be as inscrutable as his lyrics, which in Yes's early-1970s heyday spawned a small industry around explicatory pamphlets.

Then he steps back into 2003 to say that he is still creating as much today as when he started writing music, and only an hour ago penned these words to a song he calls "When":

"When I hold you and cup you to my body I am home again

When watching you I forget where I am

When the night light flickers around the room of my soul

When I bask in the warmth of your smile

When every child should dream and sleep the perfect dream

When our food is just enough to satisfy our hunger for more

When we start to tell our friends they are so real and loved

When the clouds celebrate each draft of wind

When our collective voice sings in tune with mother Earth ..."

Then he stops and laughs. "When all that happens I will be a very happy guy," he says.

IF ANDERSON seems esoteric that's nothing compared to Yes's music, perhaps the most progressive of progressive rock.

Listen to the early 1970s albums "Close to the Edge" or "Fragile" and you'll understand that rumors of progressive's resurrection are premature. No current band bears the remotest resemblance to Yes -- also featuring Steve Howe, Rick Wakeman, Chris Squire and Alan White.

The group's songs -- all very long -- are packed with tricky, neurotic riffs, lurching shifts in tempo and time signature and keyboard solos that stretch into next week. That's before you get to the words, which often seem incomprehensible and portentous.

"Of course it's all metaphors," Anderson says. "You need to write in metaphors to make it more mystical and through the eventual realization of what it all means you're brought to a wonderful realization of a oneness with God."

UNLESS YOU WERE there you might find it hard to believe that anything this esoteric ever found an audience. It did.

Yes was created in 1968, and by the mid-1970s was enormously successful, particularly in the United States. The group last played Honolulu in 1987.

During the progressive music boom of the early '70s, Yes was rivaled only by Emerson, Lake & Palmer, and Genesis, for a particular brand of classical-laced rock that initially was refreshing and innovative.

Success bred staggering indulgence. Capes were worn on stage and mansions were bought. Howe reportedly would fly his Gibson guitar in its own seat on the Concorde. When Yes could not decide whether to record in London or "in a forest at the dead of night" -- Anderson says the latter was his idea -- a compromise was reached: The album was recorded in an English studio decorated with bales of hay and a cardboard cow with electrically powered moveable udders.

"Well, we have matured and are quite understanding of one another after 35 years together," Anderson says, laughing. "But making music on stage is still an incredible rush, just as it has always has been.

"We've had two hit records in 35 years, but we've sustained because we love getting on stage and performing."

The positive message of Yes music helps Anderson to continually rediscover the spiritual quality of life.

"I've come to realize that all spiritual masters are the same," he said. "My quest as a musician is to be always part of that beautiful jigsaw puzzle of life ... and sing about that life."

Asked how the media treat the aging rockers, Anderson says it has no relevance.

"The media is a very small part of life, but because we're connected to the media we think that's what life's all about, and it isn't," he says. "If you start wondering about birdcalls and, um, why birds are alive and what they seem to do around us, and trees and nature and so forth, which me and my wife Jane do ... We're just such bird-lovers ... And what's wrong with that?

"Well, it was a beautiful moment. And you think life is a beautiful thing and you've got to live accordingly. You've got to magnify all your better feelings and better urges and better conscious ideas and that's your life's evolvement. There's only one reason we live. It's very simple. To find the creator. That's just my understanding; I'm still working on it."

But returning to the moment -- again -- Anderson says everyone in the band wants to be respected by the media.

"We have survived and nobody's dead yet," he says, laughing again. "I'm amazed at how well we play on stage every night. It's a continuum of growth."

But back to that "little old woman on Pensacola Street."

"She brought me into the world of meditation; we called her Divine Mother," Anderson says. "She's gone now but Jane and I still come to Honolulu every August to meet with a special group to meditate -- raising of consciousness if you like -- to understand how beautiful we really are and share our highs and lows."

Anderson's nickname in Yes was Napoleon. "It's like being a coach," he said. "I have incredibly talented people with me and they had better listen up or I'm not going to be around ...

"I believed and still believe that success is only part of our story. It makes you want to get better and better so as not to let yourself down and not to let the people down who like what you do ...

"The audience can be drunk, they can be stoned, but we have to be so good on stage. I don't want any of us to fail and have someone say 'Hey, they used to be good.' "

Anderson takes a deep, audible breath.

"The state of things at the moment is incredibly beautiful," he says. "I'm just a happy working musician."

Click for online

calendars and events.