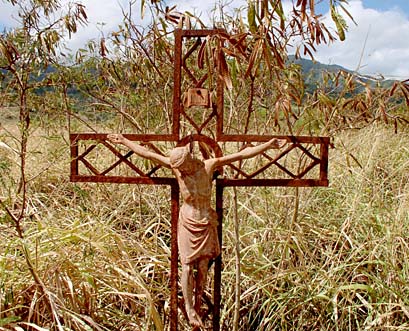

COURTESY OF ST. MICHAEL'S CHURCH

Hidden in the weeds mauka of Thomson Corner are the ruins of an 1853 stone church, where St. Michael's Church of Waialua got its start. Church members will clean the area in preparation for the church's 150th-anniversary celebration next month.

Members of St. Michael's Church

in Waialua will clear away weeds

in search of their roots

When Waialua church volunteers head into the tangled overgrowth of Waialua Sugar Co. land next Saturday, they will be taking a step back in time.

Hidden in the weeds mauka of Thomson Corner are the ruins of an 1853 stone church, one of the first Catholic churches in Hawaii. Members of St. Michael's Church will bring machetes and sickles to clear the ruins and the old church graveyard in preparation for the 150th-anniversary celebration next month.

They will return with leis on Sept. 28 to memorialize the parish founding. The story of St. Michael's is a beginning chapter in the history of the Catholic Church in the islands. It was not priests, but a zealous convert, Luika Kaumaka, who planted the parish nearly 20 years before that stone church was built.

Festivities will continue throughout the day at the church and school on Goodale Avenue. Catholic Bishop Francis DiLorenzo will preside at a 10 a.m. Mass. Tickets at $10 each are on sale at the church for the anniversary party, which will include lunch and musical entertainment.

The party will also mark the 50th anniversary of Sts. Peter and Paul Mission church, which serves members at the Sunset Beach end of the parish.

Kaumaka had been baptized in Honolulu by one of the first French missionaries, the Rev. Alexis Bachelot. In 1831, Bachelot and other priests were expelled from the islands by the kingdom in response to the influence of Protestant missionaries. They were not allowed to return until 1839.

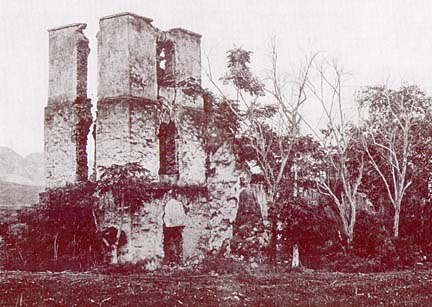

COURTESY OF ST. MICHAEL'S CHURCH

St. Michael's Church, Waialua, built in 1853.

Kaumaka took her apostolate well beyond the eyes of government, to the distant North Shore. There she began teaching the faith to Hawaiians in the small community known as Paalaa on the banks of Paukauila stream.

By the time the Rev. Joseph Desvault arrived there in 1840, there were 96 people seeking to be baptized, according to records compiled by the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary.

The enthusiasm of his ready-made flock influenced the priest to persuade Bishop Jerome Rouchouze to make the long horseback ride to Waialua from Honolulu to baptize Kaumaka's catechumens.

A small thatched-roof chapel built by the Hawaiians sufficed as the worship space for the next 10 years.

In 1848, King Kamehameha IV granted a royal patent for a strip of land for the church. The building dedicated on May 8, 1853, as St. Michael the Archangel had been built by parishioners using rocks from the surrounding fields and coral pounded into lime for concrete.

Economic changes on the far corner of the island led to a shift in the makeup of the congregation and an eventual move to the new location nearer the sugar mill. As the land was acquired by the plantation and taro fields gave way to sugar, many in the Hawaiian population moved away. In the 1880s, Portuguese immigrants arrived to work on the plantation, to be followed by workers from the Philippines.

The old stone church was left behind in a land exchange that brought St. Michael's closer to the plantation's main camp. A wooden-frame building completed there in 1912 burned to the ground in 1923.

Roger Vierra, 78, third generation of his family to attend St. Michael's, remembers his parents talking about the fire. But his altar boy service was in the "new church," a concrete building with a tile roof, modeled after the mission of San Gabriel in Southern California, which has been the center of worship for North Shore Catholics since 1923.

Vierra retired as a heavy equipment operator with the sugar company. He is the grandson of a Portuguese immigrant plantation worker and son of a Waialua Sugar Co. truck driver.

COURTESY OF ST. MICHAEL'S CHURCH

Ruins of the first St. Michael's Church.

"At one time we got together to clean the old graveyard, but since the old-timers went, we haven't bothered," he said.

The church was a center of social life in those old plantation days, he said. "When they built the gym, it was the first recreation hall in the area. The community played basketball there.

"I was altar boy. I was in the Holy Name Society. I remember the bazaars. I liked to work the throw-ball booth," said Vierra.

Nowadays he hauls his potted arica palms to decorate the sanctuary at the Sts. Peter and Paul Mission.

Two Masses are celebrated Sundays at the mission church, which was established at the far end of the parish in 1953. Its 100-foot bell tower is a landmark at the edge of Waimea Bay, occupying an old rock-crushing plant.

A few of the fourth, fifth and sixth Vierra generations are among the 900 members on the parish rolls. Even though most have moved from Waialua, "they feel the ties," said his daughter Debbie Vierra. Her five siblings have brought some of their 10 children and five grandchildren to be baptized at St. Michael's.

Gregory DelaCruz interviewed Roger Vierra and other old-timers in researching parish history for a brochure to be distributed for the anniversary.

"I think a lot of people have made contributions to the parish, trying to build dwelling places for the Lord," he said. "These people went through hard times. They have fascinating stories. I have always been interested in their kindness and generosity."

DelaCruz's Philippine-born father worked for the sugar company, and his parents were married at St. Michael's in 1944.

"My dad was active in the church community. The three of us boys attended the school."

St. Michael's School was started in 1944 as a kindergarten and was expanded to eight grades by 1949. There are currently 230 children enrolled in the preschool and elementary school.

Although his research took him to the State Archives and the Catholic diocese records, DelaCruz had no luck in finding out whatever happened to Kaumaka. Her story was told in the booklet published for the 120th anniversary, based on parish records, and it used to be printed in the Sunday bulletin, he said.

Some names are still readable on the old gravestones, but no one knows if she is buried there.

Next Saturday, volunteers will clear the weeds and try for a closer look at their roots as a congregation.

Click for online

calendars and events.