DEAN SENSUI / DSENSUI@STARBULLETIN.COM

Deserie Watson-Kaluhiokalani showed her graduation certificate to son Ikaika Maunakea, 8, who was holding an engraved wooden certificate that she also received on Friday. Looking on were nephews Lopaka Kaaiawaawa, 12, and Kekoka Kaaiawaawa, 11.

Apprentices keep

yard shipshapeDemand is high for a program

that mixes work at Pearl Harbor

with a college degree

Deserie Watson-Kaluhiokalani's plate is full, to say the least.

A single mother of a third grader at Kamehameha Schools, she has been juggling classes at Honolulu Community College, working nights as an apprentice crane mechanic at Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard, playing tackle for the Hawaii Women's Professional Football League and competing in Super Brawl, where she is the reigning female champion.

"You just have to have the mindset," said Watson-Kaluhiokalani, who on Friday was among the 104 men and 10 women graduates of the Pearl Harbor Shipyard's four-year apprenticeship program, run in conjunction with Honolulu Community College.

Pearl Harbor had an apprenticeship program since 1924, with as many as 4,000 journeymen moving through its ranks. But it died in 1994 as the Navy began to downsize its fleet and cut back on jobs at Pearl Harbor. In the last decade the number of civilian workers, which was as high as 8,000 at one point, has been cut by almost half.

Local shipyard leaders took their concerns to U.S. Sen. Daniel Inouye who got Congress to appropriate $15 million to restart the program in 1998 not only at Pearl Harbor, but at the naval shipyards at Puget Sound, Wash., Norfolk, Va., and Portsmouth, N.H.

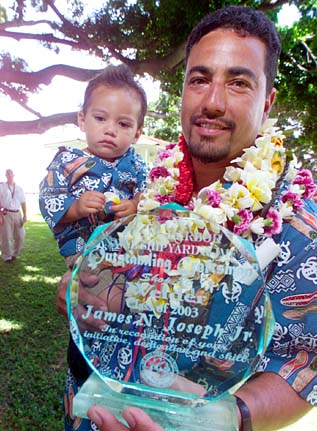

DEAN SENSUI / DSENSUI@STARBULLETIN.COM

James Joseph Jr. held his 2-year-old son, James Joseph III, and his award for outstanding welding craftsmanship at Friday's ceremony. Joseph said he enlisted in the program for its stability and opportunities for better pay.

The initial funding was to ensure training for at least 125 apprentices a year at these four shipyards, an aide to Inouye said. Since then the Navy has included funding for the program in its annual budget.

Capt. John Edwards, shipyard commander, said apprentices now make up 25 percent of the Pearl Harbor civilian labor force of about 4,700.

Inouye said at Friday's graduation ceremony that the program is "a demonstration of the critical importance of Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard," adding that he expects the workload to increase as the Pentagon shifts more of its forces to the Pacific.

In 1999, the Navy formed a partnership with Honolulu Community College, which provided the instructors and gave the apprentices the opportunity to earn an associate degree after two years while working part-time at the shipyard. The apprentices could pick jobs within 17 trades.

Watson-Kaluhiokalani was a member of the first class and had to attend classes in the morning at Honolulu Community College.

"It was tough," said Watson-Kaluhiokalani, a 1982 graduate of Farrington High School. "We had to pay for our classes during the first year. Classes were in the morning at Honolulu Community College, and then in the evening I had to work at the shipyard."

By 2001 all the classes were held at Pearl Harbor and the Navy was paying for them.

Jeannie Shaw, Honolulu Community College educational coordinator, said the students now only pay for books and supplies.

The demand is high, with nearly 3,800 people applying this year.

"However, only 3,000 were tested," Shaw said. "About 545 were interviewed by shipyard officials, and 200 were selected."

That number will be whittled down further over the next months as each candidate undergoes security clearance checks and physical testing before starting classes in January.

Shaw said the students enrolled in the apprentice program must maintain a 2.0 grade point average while in the program.

James Joseph Jr., who received the shipyard apprentice's outstanding welding craftsman award Friday, said he enlisted in the program because "it was stable and offered better pay in the end."

"Here you can build a career," said Joseph, who worked for a private shipyard as a pipefitter before he joined the apprenticeship program in 1999. "You don't have to worry every Friday about getting a pink slip, getting laid off and collecting unemployment until the next job."

Watson-Kaluhiokalani, 39, also cited job security as a major benefit of the program. She had been working as a laborer on the H-3 freeway and noted that "you didn't work when the weather was bad."

While she was attending classes at the community college to get a degree in refrigeration repair, Pearl Harbor officials stopped by looking for recruits. She joined the program as a crane mechanic apprentice, initially earning nearly $14 an hour. Now she will be making nearly $25 an hour as a journeyman.

Shaw said there were built-in raises every six months for the apprentices as long as they stayed in the program and kept up with the work. The program has a high retention rate, with 98 percent of participants finishing.

"They go to school together for two years. They are very cohesive, with the stronger students helping the weaker students," Shaw said.

Joseph, a 1990 Waianae High School graduate, said he has seen what working at Pearl Harbor can do for an individual.

"My dad worked here for 31 years, retiring in 1995 as a senior foreman," Joseph said. "A job here gave him the chance him to buy three houses.

"This program means more training, more time to do quality work, which ended up in better production, better managers, better safety and better pay."