CRAIG T. KOJIMA / CKOJIMA@STARBULLETIN.COM

Leighton Kaina, above, a student working with University of Hawaii researchers, lights up a methane ice ball. Stephen Masutani of the University of Hawaii is researching the use of methane hydrates as a potential fuel source.

University of Hawaii researchers

study a form of methane gas

as a potential fuel source

Deep in the world's oceans lies a frozen form of methane gas with twice the total energy contained in all fossil fuel reserves.

Methane hydrate is a naturally occurring chemical combination that "locks" methane gas within an ice crystal under high pressure conditions, like those found in the deep ocean and arctic permafrost.

University of Hawaii professor Stephen Masutani heads one of a handful of research teams in the world studying the properties and potential use of methane hydrates as a fuel source when oil, coal and gas reserves run out.

When a laboratory sample of methane hydrate is lit with a butane lighter, it looks like an ice cube on fire. That's essentially what it is.

The U.S. Naval Research Laboratory calls methane hydrates "frozen, clean energy from the sea." But whether that energy can be unlocked in a cost-effective way, without damaging the environment, remains to be seen, Masutani said.

CRAIG T. KOJIMA / CKOJIMA@STARBULLETIN.COM

A piece of methane ice burns.

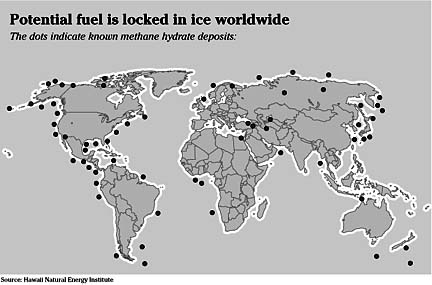

Methane hydrate deposits are found along continental shelves, but not in Hawaii. Still, the university's Hawaii Natural Energy Institute received grants for the research because of its experience simulating deep-ocean conditions and because it is also studying ways to improve fuel cells. Fuel cells are an energy-conversion system that converts hydrogen and oxygen into water, producing electricity and heat.

Fuel cells and methane hydrates both involve hydrogen energy and "methane is considered to be a good source of fuel-cell fuel," Masutani said.

Methane hydrates research accounts for about 35 percent of $7 million granted to Hawaii-based energy projects by the Office of Naval Research since 2001, said Richard Rocheleau, the institute's director.

"There are issues to address, but I think it has great potential," Rocheleau said.

The other 65 percent of the Office of Naval Research money helps support the Hawaii Fuel Cell Test Facility, which opened in April.

Over the past three years, Masutani's team of post-doctorate, graduate and undergraduate students in molecular bioscience, bioengineering, geophysics and microbiology has been chipping away at some of the problems that must be solved if methane hydrate is to be harnessed for human use.

They're asking whether people can:

>> Precisely identify the quantity and quality of methane hydrates at ocean depths of 1,800 feet or more.Masutani admits that the ultimate answer to all the questions may end up being "No.">> Safely and sustainably extract methane hydrate from ocean-floor sediment and use it as an energy source.

>> Use the methane hydrate energy to run low-power scientific and military surveillance instruments on the ocean floor or fuel unmanned underwater vehicles.

But, he said, the possibility that even 1 percent of the estimated 300,000 trillion cubic feet of methane locked away in methane hydrates might be usable makes the research worthwhile.

Commercial use of methane hydrates, even if it all comes together, will likely be 20 or more years away, Masutani said. And even if all those challenges can be hurdled with technology that's not more expensive than it's worth, there are other problems.

Though it burns cleaner than coal or oil, methane gas still produces carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas that contributes to global warming. Any large-scale burning of methane hydrate would need to address that and the fact that methane, also a greenhouse gas, could escape to the atmosphere.

"You can't just go in there, guns blazing and say, 'We have an energy need,'" and mine methane hydrate regardless of the consequences, Masutani said. "Even if hydrates are not commercially exploited for energy, the specter of methane release (to the environment) ... needs to be carefully examined."

Masutani said the vicious cycle could go like this: Global warming, caused in part by burning fossil fuels, increases the oceans' temperature. Methane hydrates in the ocean then rise to a temperature that releases the methane gas, which enters the Earth's atmosphere and further hastens global warming.

Scientists suspect that sudden releases of methane from ocean-floor sediment could create undersea landslides and resulting tsunamis. Those releases might be caused either by global warming or by inept human removal of methane hydrates.

Inorganic chemist Traci Sylva's role at the institute is studying how methane hydrates form and decompose. Her work includes meticulous heating and cooling of methane and ice crystals to form methane hydrates in the lab.

Geophysicist Thomas Gorgas develops ways to locate methane hydrates in the sea floor by using sonar. He coordinates directly with Naval Research Laboratory researchers, going on voyages with them to collect undersea samples.

Microbiologist Brandon Yoza studies the deep-sea microbes that create methane. Together with master's degree candidate Ryan Kurasaki, he is trying to develop a "biological fuel cell" that uses methane-creating and methane-eating bacteria like the two poles of a battery.

"From the pure science perspective, how everything interacts with each other to produce things is fascinating," said Masutani, who is an engineer. "Is it practicable is the big question."

It's going to take a while to figure that out.

BACK TO TOP |

Methane hydrate at a glance

>> A high proportion of methane hydrates is located off the Gulf of Mexico.>> Because of the high pressure of the deep ocean, methane hydrate crystals form at temperatures above freezing.

>> Tiny worms called ice worms can live in methane hydrates.

>> Much of the methane hydrate is made by deep-ocean micro-organisms.

>> If humans ever colonize the planet Mars, methane hydrate deposits there might be usable as an energy source.

>> Along with high-tech equipment, one of the tools used to create methane hydrate in a University of Hawaii at Manoa lab is a hand-cranked shave ice maker.

>> Until recently, methane hydrates were considered a nuisance in deep-ocean prospecting for oil, rather than a potential energy source.

On the Web: www.hnei.hawaii.edu