KITV

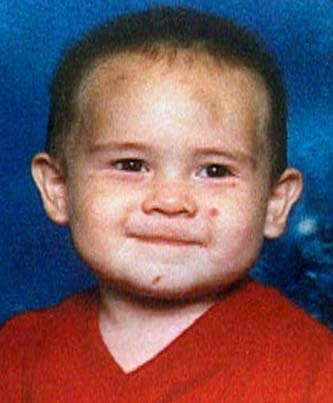

A family photo of Jose Flores shows noticeable bruises on his face. More than a month after the Waipahu boy's death, no one has been charged in the case.

Why Jose died

The failure to save a

2-year-old boy raises doubts

about social services

When Jose Malachi Flores, 2, began limping one morning this spring, his baby sitter spotted it and his mother, Maria Carmella Flores, drove him to St. Francis-West Medical Center, according to homicide Detective James Anderson.

Anderson said doctors diagnosed Jose with a spiral fracture of the left leg, an injury that occurs when a leg is wrenched or twisted either from a fall or, in some cases, as a result of child abuse.

Flores later told Anderson that she thought it was an accident. So health care workers, who have a responsibility to report suspected child abuse, did not alert Child Protective Services or the Honolulu Police Department.

A few weeks later, Jose died of head injuries that the medical examiner attributed to "shaken baby syndrome," a form of child abuse in which a child is so severely shaken that the brain swells, the backs of the eyes can hemorrhage and, in 50 percent of cases, the child dies. Survivors often have severe disabilities.

Jose's death on April 24 once again raises questions about the social systems that should have protected this child and failed. In addition to CPS and the police, that social system includes health care workers, neighbors, friends, caregivers or family who might have suspected abuse but did nothing to report it.

"Somebody knows who did this," said Sulema Reyna, Jose's paternal grandmother, who lives in Florida and has not seen him for more than a year.

"That baby went from the baby sitter to his house every day. How many people touched that baby in a day?" she asked. "I think a lot of people shut their eyes when they saw or heard or knew something. Nobody helped him."

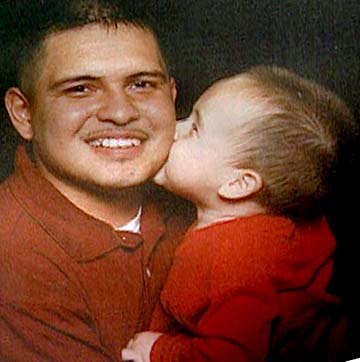

KITV

A family photo shows Jose Flores with his father, Jose Manuel Flores.

Reyna, her voice swelling with anger and grief, added, "It's inhuman if you see or you know (about abuse) and you keep your mouth shut."

Lillian Koller, the newly appointed director of the Department of Human Services, which oversees CPS, said: "This is a terrible tragedy. We need to re-evaluate the processes and systems involved in child protection. It's not CPS alone. Schools, police departments, medical providers, the courts all have a role to ensure child protection."

CPS gets more than 15,000 calls a year and not all are investigated, said Koller. Instead, intake workers conduct a risk assessment to decide if a complaint should be evaluated. In 2002, CPS investigated 6,689 cases and confirmed child abuse in 54 percent of the cases. Jose's case was not confirmed after two separate investigations.

Koller said they are studying Jose's case to determine where improvements can be made.

A series of high-profile child-abuse cases in Hawaii in the late 1990s led to some changes in the system. Jose Flores' legacy, like that of Reubyne Buentipo Jr., may be further changes to a system that still fails. In 1997, when Reubyne was 4, his mother beat him into unconsciousness, causing massive brain damage. The outcry over that case led to the passage of "Reubyne's Bill," which altered the way CPS reunites children with parents.

In 2002, four children who had been under CPS investigation died. The medical examiner ruled all four deaths to be accidental or natural. This year, nine children under CPS investigation died. To date, six have been ruled accidental. The medical examiner has ruled Jose's death a homicide and two other deaths have not been determined.

More than a month after the Waipahu boy's death, no one has been charged in the case. The 23-year-old baby sitter was arrested April 25, the morning after Jose died. But police released her pending further investigation.

In private, police, child-abuse experts and a former prosecutor admit the Flores case is complicated and in the end might be difficult, if not impossible, to prosecute.

Jose's 22-year-old mother and 23-year-old father, Jose Manuel Flores, both declined repeated requests for interviews, as did the baby sitter.

While the murder inquiry continues, it's clear the system that failed Jose also needs investigation.

CPS and HPD both investigated complaints of child abuse to Jose in August and November that involved accusations of bruises and burns. They investigated several people in Jose's daily life, some of whom are suspected in his murder, and found the accusations unfounded, according to Koller and police.

Koller said: "We (CPS) did our thing, and the police did theirs. Our cases were closed, and it looks like it went through the process as it was supposed to."

She also noted that CPS's jurisdiction is more confined than that of the police because it is limited to investigation of family members and licensed baby sitters.

Anderson said: "CPS went pretty far on its investigation, so it's not from a lack of CPS investigating. They are pretty intense in these cases, sometimes more so than the police."

He added, "CPS did the right interviews and found no red flags that the child was abused."

Reyna, Jose's grandmother, is angry at CPS.

"CPS said they did everything and that the claims were unfounded," said Reyna. "There were explanations for the bruises on his head. He had a burn on his hand, and they accepted an explanation that he got it from a grilled cheese sandwich."

Dr. Cynthia Tinsley, a child-abuse expert who formerly worked 12 years in the pediatric intensive care unit of Kapiolani Medical Center for Women and Children, said CPS workers have a difficult job and no medical expertise to help in their evaluations.

"It's hard to second guess," said Tinsley, who was Reubyne Buentipo's doctor. "CPS is trying to predict human behavior, which is very, very difficult. And we somehow expect these social workers to be more accurate than the psychic hotline."

Tinsley is critical of CPS's confidentiality policies, created by the Legislature to protect a child's privacy and prevent them from being stigmatized. But Tinsley said excessive confidentiality creates "huge communication gaps" in the system and prevents doctors from obtaining critical pieces of a child's history that might confirm suspicions of child abuse.

Tinsley said that when evaluating an injury for abuse, "you need to consider the story and the child's history (of any abuse). If the injuries or history don't match the story, that's a big red flag to report it. And I think it's better to err on the side of overreporting. But what if that history of abuse is confidential? You're missing an important piece of information. "

Tinsley said that while doctors openly share information with each other about a patient so they can assemble a clear medical history, CPS is very tight-lipped.

For example, she said that if a doctor calls CPS, he or she can only learn if a case is still active. And CPS won't give details. And if a case has been closed either because the child was placed in foster care or the claims were unfounded, the doctor cannot get information. Tinsley said she had cases in which she was concerned about a child and CPS confidentiality prevented her from learning that a sibling had been abused or taken away.

Koller agreed that this lack of information is "a huge problem" that should be corrected by changes to the current laws governing CPS.

"For the doctor it's really a one-way street," said Koller. "They call the CPS hotline with a case, and CPS can't say much because of the law. The doc can give us information and ask for advice whether a mandatory report (of abuse) should be made (to CPS). But really, as the laws now stand, we can't give information that would help the doctor make an informed decision."

Koller said, "We really need to revise the existing laws so that CPS can effectively communicate with doctors."

She added: "I'm not convinced that having such a closed system helps the child. I think the confidentiality actually feeds (rather than prevents) the stigma and shame for the child. And the child is the victim and shouldn't feel shame. I think if we had an open system, that exists in some other states, there wouldn't be shame and there would be more accountability."

Tinsley also said that CPS workers make their decisions without using any medical experts or evaluations. Often when child-abuse teams review a case going to court, they only have medical evidence if the child was taken to the hospital.

In Jose's case, doctors diagnosed the spiral break as a "toddler's fracture" that came from a fall and not abuse. But would someone have reported it anyway, if they had known there were two previous investigations for child abuse?

Anderson, the deputy medical examiner who performed the autopsy, child-abuse consultants and others involved in the investigation say there are many complications in Jose's case.

One factor is the rocky relationship between Jose's mother and his father, an Army cook based at Schofield Barracks. In fact, many of the people who touched the toddler's life, from baby sitters to family members and friends, have conflicts with one another, which complicates both the murder investigation and the previous child-abuse inquiries.

Last summer, the Flores' strained relationship and accusations against one another were documented in police reports and court cases.

In July, Maria Flores, who was living in Waipahu with her boyfriend, Lino Innis, took out a restraining order against Jose Manuel Flores, to keep him away from her and her child.

In August, she was granted temporary custody. Jose Flores was ordered to stay away from his wife and son and to take anger management classes, substance abuse testing and parenting classes. He was allowed visitation but only under the supervision of designated military personnel.

Later in August, Flores challenged his wife's temporary custody, arguing she had abandoned the child for two months with a baby sitter, Sabrina Grace, and only visited him six times.

That same month, Grace complained to CPS that when the child was not in her care he came back to her with "big bruises on his face and head."

In an interview, Grace said "these were no small tap bumps. These were big, protruding out of the head. He should have been taken to the doctor."

Grace said: "I tried to protect Miho (Jose) and alerted CPS. But CPS didn't understand what was going on. If CPS had listened, that boy would be alive today."

Although Grace called CPS, she had a falling out with Maria Flores and was acting on behalf of Flores' estranged husband. Koller confirmed her complaint. Both CPS and HPD investigated.

Sources close to the investigation said the investigators saw the angry, jilted father as a "tainted messenger" and did not give full weight to his complaints.

"They blew him off," said Reyna, Flores' mother. "When Jose tried to help his son, no one would help him."

Reyna said that at Christmas her son took Jose to Wal-Mart for pictures, and Jose had bruises on his face and back.

"The Christmas picture I have of him, my last picture of him, he has bruises on his face," said Reyna.

Koller agreed that judging the person who makes the complaint is a problem.

"It's not appropriate for the investigator to judge the credibility of the messenger," she said. "They should independently and dispassionately investigate the facts."

Koller added, "Of course, when there is no physical evidence, then they have to rely more on the credibility of who's making the complaint."

By September, Maria Flores had hired a new baby sitter, a young woman in Ewa Village. The woman took care of six children, including two of her own, in the small and tidy plantation-style house that she shared with her brother and boyfriend.

In November, Jose Flores complained again to CPS, this time getting an Army officer to make the call. Koller confirmed the complaint. Both CPS and HPD investigated and found nothing.

On April 22, Jose's mother dropped him off at the baby sitter at 6:45 a.m., according to Anderson. Around 10:30 a.m., said Anderson, the baby sitter fed Jose. Sometime during the day, the baby sitter noticed Jose was not feeling well and called his mother to pick him up. She did not.

At 5:15 p.m., when Innis, Maria Flores' boyfriend, came to pick up the child he was unconscious and "breathing laboriously," said Anderson. Innis called an ambulance.

When the child was examined at St. Francis he had massive swelling of the brain, a blood clot on the brain and bilateral hemorrhaging, said police. The attending physician immediately suspected shaken-baby syndrome. As a military dependent, Jose was later transferred to Tripler Army Medical Center, where he underwent surgery to relieve the swelling on his brain in a last attempt to save his life.

When Lt. Brit Nishijo and members of the HPD's child-abuse detail arrived at the hospital in the hours after the child was brought in, they were briefed on his condition.

"It was critical. We just called homicide and passed the case to them," said Nishijo.