CRAIG T. KOJIMA / CKOJIMA@STARBULLETIN.COM

The DFS Galleria Waikiki provides 90 percent of DFS Hawaii's revenues. DFS, in turn, pays for about 40 percent of the state's airport operating costs

One-way ticket Hawaii's sole airport purveyor of duty-free goods has been the biggest single source of operating income for the state's airports over the past 40 years.

A single firm can make

or break state airportsBy Russ Lynch

rlynch@starbulletin.comIn the process, the company, DFS Hawaii, has done very well for itself.

So well, in fact, that French luxury-goods giant LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton was willing to pay $2.5 billion in late 1996 for a little more than 60 percent of its parent company, DFS Group, based in San Francisco.

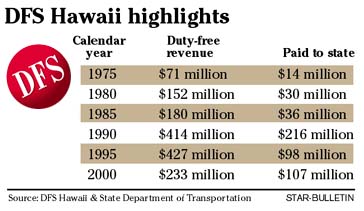

That made the DFS founders, a handful of partners, very rich indeed. The Hawaii operation alone, riding on years of booming Japanese tourism, has taken in nearly $8 billion in revenue since it opened a small store at Honolulu Airport in 1962.

And Paris-based parent LVMH has grown, too, mostly recently reporting sales of $13.7 billion for 2002 and an $880 million net profit for that year, 145 percent more than in 2001.

Concession fees traditionally make up more than 60 percent of the revenue for the state's commercial airports and at times have contributed as much as 70 percent.

DFS produces about two-thirds of all the concession fees, meaning DFS covers 40 percent or more of the operating costs of the airports.

That money has helped pay wages and other expenses and has boosted the state's ability to pay debt service on the bonds and other financing it uses to pay for capital improvements.

That has particularly benefited some neighbor island airports.

In fiscal 2002, not a good year, concession fees produced 56 percent of the operating revenues for the state's airports. In good years, that has gone above 72 percent.

Owen Miyamoto, a long-time head of the airports system, told the Legislature last week there was no way a facility of the relatively small size of Kahului Airport on Maui could have afforded an 11,000-foot runway without financial help from outside, and much of that help was made possible by concession fees paid at Honolulu Airport but which support the whole state system.

DFS likes to point to1970, when it successfully bid $69 million for a 10-year contract at the same time the state was trying to figure out how to pay for the new Reef Runway.

In essence, news reports said, DFS would pay for the runway. During that contract period, DFS took in $716.5 million in gross sales.

The beginning

A handful of American friends in the late 1950s started a business in Hong Kong selling imported luxury goods, mostly European, to travelers headed for foreign points.Their wrinkle was to keep the goods "in-bond," not legally entering the country, until they were sold and carried away overseas. That meant no import duties or other taxes, which in turn meant lower prices and good business.

By the early 1960s, the group, headed by Charles Feeney, had branched out to Hawaii, opening a small duty-free shop at Honolulu Airport under the name Duty Free Shoppers. The partners were on their way to a fortune.

Their business did so well over the years, as Japanese tourists discovered Hawaii, that DFS expanded to San Francisco and other international travel terminals on the mainland and around the world.

The success is what attracted Paris-based LVMH to buy majority ownership in the company years later. It would have bought DFS entirely, but one partner, Robert Miller, declined to sell his shares and after a court battle held on to 39 percent of the company, which he still owns.

Out of the airport

Along the way, helped by an outlet in the center of Hawaii's tourist trade -- now the 160,000-square-foot DFS Galleria Waikiki -- the business became the major source of revenue for Hawaii's state-owned airports, paying more than $2 billion in concession fees over a 40-year period.DFS' Waikiki Galleria now produces some 90 percent of its duty-free sales as Japanese tourists come in at their leisure and select their merchandise in a showroom open only to those with tickets for overseas flights.

Then the tourists don't have to worry about the goods until they pick them up in the international section of the airport on their way home.

Until recently that has been very good business for DFS. So has the retail business in the same building, operations that have nothing to do with the state's concession.

That setup has drawn criticism too, from some who say DFS has made it almost impossible for any other operator to bid for the duty-free concession because no other firm has such a Waikiki facility.

One observer who was close to the business in its better days, who decline to be quoted on the record, said the state would have to find a way to offer premises like that as part of the deal if it wanted to attract real competition.

DFS does not agree. There are other spaces in Waikiki that could be used in a similar way, the company said.

New reality

Now that the shine has faded from Japanese tourism, first due the widespread economic crisis in Asia in the late 1990s then again by 9/11 and the Iraq war, DFS' wealth has brought out critics who find it hard to accept the argument that the company cannot pay its full rent without going bankrupt.The company has a very rich parent and has done very well until recently, so it shouldn't be moaning now about a temporary setback, the argument goes.

But DFS says LVMH has helped with loans but won't provide anything more, and nobody else is willing to lend to it in such a tough retail environment.

DFS says international travel has dropped so much that the company should not be expected to pay the minimum $60 million a year concession fee it bid when times were better.

"We are paying 50-60 percent of the minimum annual guarantee for the duty-free concession," said Sharon Weiner, group vice president of DFS Hawaii.

DFS wants to be relieved of having to pay the minimum $60 million a year and move instead to a percentage of revenues. "There is an upside in the proposal we are making," she said.

If the Japanese do come back, the DFS formula could produce more than the $60 million guarantee, Weiner said. But, she acknowledged, a significant return of Japanese travelers is unlikely.

Not alone

DFS is not the only concession holder hurt by the fall in international travel. Peter Fithian, owner of Greeters of Hawaii, heads a committee of airport concession holders, including DFS.

All the concessions have the same problem, Fithian said. None of the concessionaires is paying the minimum concession fee because the drop in airport business from 9/11 hurt them all, he said.

The concessions have been lobbying vigorously for a bill in the Legislature that would let proven money-losers cancel minimum rent and instead pay a percentage of their revenues until times improve.

The state and DFS reached a deal Friday where the company would pay $25 million to the state and the two sides will negotiate a new arrangement.

DFS did almost exactly that at Los Angeles International Airport and got a new contract based solely on a percentage of revenue, with no minimum guarantee.

The company said it paid because it had a reliable assurance that the airport authority would agree to a temporary percentage-rent deal, reinstating the minimum guarantee only when business improved.

DFS Group LP