|

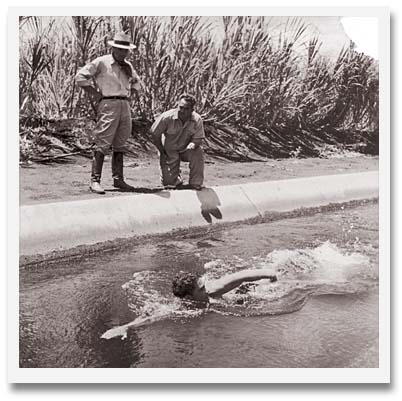

Maui coach’s legacy PUUNENE, Maui >> He was a sixth-grade teacher who started a swimming program in a sugarcane irrigation ditch on Maui and told his young swimmers they could become athletes representing the United States in the Olympics.

shines like gold

Soichi Sakamoto helped isle kids

achieve Olympic dreamsBy Gary T. Kubota

gkubota@starbulletin.com

In three years under Soichi Sakamoto's coaching, the youths on the Valley Isle won the national Amateur Athletic Union outdoor men's team championship twice.

Soichi Sakamoto

Several of the Maui swimmers could have qualified to represent the United States in the Olympics in 1940 and 1944, if World War II had not occurred resulting in their cancellations.

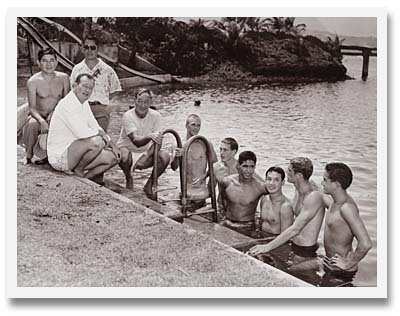

Sakamoto and his swimmers from the late 1930s through the 1950s are a part of a photographic exhibit at the Hawaii State Library in Honolulu through the end of the month, sponsored by the Hawaii Swimming Legacy Project.

Sakamoto, who died at age 91 in 1997, has a public swimming pool named in his honor in Wailuku and was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame in Florida in 1966.

Now the goal is to raise enough money for a Hawaii Swimming Hall of Fame Museum and publish a book about the accomplishments of swimmers statewide.

"We want to inspire a new generation of swimmers in Hawaii," said Sonny Tanabe, a Honolulu resident who swam in the 1956 Olympics games and was coached by Sakamoto.

One of Sakamoto's swimmers, Fujiko "Katsutani" Matsui, who won the national AAU title in the 200-meter breaststroke in 1939 and 1940, was just inducted into the Hawaii Swimming Hall of Fame.

Matsui qualified to represent the United States in the 1940 Olympics but never participated because it was canceled as a result of World War II. "Of course, I was disappointed because of all that work," she said.

Although two successive Olympics were canceled due to World War II, Sakamoto continued to train swimmers, many of whom became national champions.

He moved to Oahu and served as swimming coach from 1946 through 1961 at the University of Hawaii, where his swimmers won a number of gold, silver and bronze medals at the Olympics.

Some swimmers said his legacy was not only developing Olympic champions, but also creating technical innovations and inspiring children of sugar plantation laborers to pursue their Olympic dreams.

|

From the ditch to pool

Along a central Maui dirt road near the old Puunene School where Sakamoto taught science and health in the late 1930s, the concrete ditch that once challenged youths to swim against the current still carries water to the fields.But weeds have grown along the edges, and the lines marking the number of swimming yards have faded away.

Only a few vacant buildings stand in Puunene town, where workers once lived in nearby ethnic camps.

Sakamoto made the sons and daughters of plantation immigrants dream of becoming Olympians by starting a swimming program in the 1937 called the "3YSC" or Three-Year Swim Club, asking youths to train hard for three years to make the U.S. Olympic team.

Former state House member Keo Nakama, the son of a sugarcane laborer, who swam for Sakamoto, remembers the supervisors on horses chasing youths from swimming in the ditches.

Nakama said Sakamoto persuaded a supervisor to allow the youths to swim in the ditch as part of a swimming program.

Nakama said the plantation had a swimming pool, but it was reserved for the use of supervisors and their families.

He said soon after Sakamoto's swimmers received recognition at a swimming competition against state champions, the plantation began to ease restrictions and his swimmers were able to practice at the supervisor's pool at night.

Later in 1937, the plantation completed a public swimming pool at Camp 5, where Sakamoto's swimmers were able to practice daily after school until 9:30 p.m.

In the summer, practice started at 5:30 a.m. and went into the night.

"He told us not to come if we came later than that and not to come anymore," recalled Matsui. "He was strict."

Sakamoto himself was not a great swimmer.

Matsui remembers seeing Sakamoto once in the swimming pool. "He couldn't really stroke, but he would tread in water to keep himself alive," she said.

"He was a great coach. Some people have gifts in certain things. I can't coach, but I was a swimmer."

Inventing equipment

Swimmers said Sakamoto introduced a number of innovations in conditioning athletes, including interval swimming and the use of pulleys and weights.He built his own equipment to develop certain muscles in swimmers.

One device attached weights to steel rods that swimmers could push from a sitting position to strengthen their legs.

Another made of rubber and connected to weights was used as a pulley, allowing swimmers to strengthen their arm strokes.

At that time, conventional swimming coaches criticized Sakamoto's use of weight training and predicted he would ruin his swimmers.

Now, weight training is a part of virtually all competitive swimming programs.

Sakamoto's daughter, Janice Lam, recalled him studying film of his swimmers late at night to find a way to improve their techniques.

Lam said her mother Mary supported her father's endeavors, cooking for the team, outfitting them in aloha print uniforms with lauhala hats, and entertaining the crowds by dancing the hula during intermission when they traveled to swimming meets on the U.S. mainland. "My mother was something else," she said.

While still at Puunene, her father also worked on remaking the swimmers identities by giving them English nicknames like "Chic" for Chieko and "Fudge" for Fujiko, she said.

Lam said her father had a desire to help youths from modest backgrounds, because he was acutely aware of his own.

Before emigrating to Hawaii, Sakamoto's mother had been raised in an orphanage in Tokyo.

Lam recalled her father telling her how he had been hit by a truck as a child on Maui and nearly died.

"He literally felt he was saved by God for some kind of work," she said.

Hawaii champions

At national competitions sponsored by the Amateur Athletic Union, Matsui took first place in the 200-meter breaststroke in 1939 and 1940, the last event qualifying her for the Olympics team.There were no U.S. men's trials for Olympic swimmers in 1940, but many of the male swimmers distinguished themselves at national and international competitions.

Besides being a part of the Maui team that won the AAU men's championship in 1939 and 1940, Nakama received numerous awards in swimming, including five gold medals in the Pan American Swimming Championships in Ecuador and five titles at the Australian Nationals in 1939.

Takashi "Halo" Hirose, another Maui swimmer under Sakamoto, was also on the United States team in Ecuador.

Nakama's brother, "Bunmei," and Bill Smith, representing the Sakamoto's team on Maui, finished first and second respectively in the mile at the AAU swimming meet in Santa Barbara, Calif. in 1940. Smith, a retired water safety director for City and County of Honolulu, went to Maui in 1940 to train under Sakamoto.

Nakama said he was disappointed when the Olympic games were canceled in 1940 and 1944.

But he said he felt fortunate that swimming allowed him to obtain a scholarship at the Ohio State University and to travel internationally. Eventually, he earned a master's degree in education and served in the state House for 10 years.

Smith followed Nakama to the Ohio State University, swam in competitions representing the Navy, and later trained intensely under Sakamoto for six months before qualifying for the Olympics after the war.

At 24, an age when swimmers then were regarded as old, Smith won the gold in the 400-meter freestyle and also in the 800-meter freestyle relay at the Olympics in London in 1948.

"I was very fortunate to have a coach like Sakamoto," Smith said. "He not only taught well, he was a great motivator."

Sakamoto, then swimming coach at the University of Hawaii, also trained Thelma Kalama who won a gold medal in the 400-meter freestyle team relay in London.

Other swimmers coached by Sakamoto include Evelyn "Kawamoto" Konno, then 18, who received the bronze in the 400-meter freestyle and 400-meter relay in the Olympics in Helsinki, Finland in 1952; and Bill Woolsey who received a gold medal in the 800-meter freestyle relay in Helsinki. In the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne, Woolsey received a silver medal in the 800-meter freestyle relay.

Life lesson: Tenacity

After World War II, the Olympic committee ruled that Nakama was ineligible to participate in the games because he taught physical education and was considered a professional.But the Olympics committee couldn't stop Nakama from swimming. He resurfaced in the news at age 40 when he became the first person to swim the 27-mile Molokai Channel in 1961.

It took him 15 1/2 hours.

Konno said swimming under Sakamoto helped her understand the key to achieving a goal.

"For one thing, you have to be tenacious in what you undertake. You stick with it and stick with it as long as you can and be focused on it," she said.

Evelyn said at age 30 while married and raising a family, she decided she would return to college to get a teaching degree.

"It was so tough because I had to take care of the family and help my husband in his business," she said. "But I didn't waiver from my goal. I had to work very hard, but it was worth it."

Donations for the Hawaii Swimming Hall of Fame may be sent to nonprofit Hawaii Swimming Legacy Project, 2199 Aha Niu Place, Honolulu 96821 or call 735-1088.