In these days of dwindling fixed-income returns, it can be tempting for investors to become enamored with bonds paying interest-rate yields in the high single digits or greater. High-yielding bonds look

tempting, but buyer bewareGenerally speaking, the higher

A bond mystery

the yield, the riskier the bondBy Dave Segal

dsegal@starbulletin.comBut with corporations today falling like dominoes, potential bondholders might want to think twice before chasing fat returns that might not be around at the end.

"The high yield looks very attractive to investors, especially to those who are used to the higher rates previously available on high-quality bonds, CDs and other income instruments," said Barry Hyman, portfolio manager and vice president in the Wailuku, Maui, office of Financial & Investment Management Group Ltd. "However, high-yield bonds pay higher income because they have higher inherent risks. In general, the higher the implied risk of a bond, the lower the credit quality and the higher the yield."

Take WorldCom Inc., for example. Its two-year bond on Aug. 1, 2001, was priced at $1,030, which was an approximate 6 1/4 percent yield to maturity. The bond is now in default and there's a high probability that bondholders will not get any of their money back.

The three major rating agencies, Moody's Investors Service, Standard & Poor's Corp. and Fitch Investors Service, assign ratings to corporate and municial bonds to tell potential investors how safe they are as investments. Bonds rated AAA, AA, A or BBB are all considered investment grade and indicate a company has the ability to repay its debt.

Those companies rated below those other levels -- from BB to DDD -- are all considered noninvestment grade, or junk. The lower the rating, the higher the risk and, generally, the higher the yield.

"High-yield bonds are always readily available because there are always companies who are struggling," Hyman said. "The high-yield bond market is enormously large. There are thousands of high-yield bond issues that investors can buy. But buyer beware."

Companies that issue high-yield bonds generally have high levels of debt and the company's income is barely enough to cover their debt payments. In some cases, it's not even enough to pay their debt. While the high interest rate might be enticing, the higher yield often indicates there's a greater chance that the issuer might default on either the interest or principal owed to the bondholder.

That's why investors often seek that tradeoff in which they accept a lower yield in exchange for the comfort of knowing they're likely to get paid.

"The key to constructing a bond portfolio is to diversify in issuers and diversify in maturities, or to buy all insured bonds and simply take a lower yield," Hyman said. "The key to managing risk are those diversifications."

Treasury securities, which have the full backing of the U.S. government, generally offer lower yields than corporate bonds but higher yields than municipal bonds. Treasury bond yields, though, are not what they used to be. On Friday, the two-year note closed at a yield of 2.07 percent, just above Monday's all-time low yield of 1.90 percent. The 30-year bond, which fell to 5.11 percent Friday, is at a nine-month low.

Municipal bonds, which also receive credit ratings, are generally issued by a city or state and are usually exempt from federal taxes. The bondholder usually can get an exemption on state taxes if the issue was from the bondholder's state of residence. They pay lower interest rates than corporate or government bonds, however, because of their tax-exempt status.

"When you're talking about bonds, you're talking about safe in several contexts," said Bank of Hawaii Senior Vice President Dave Zerfoss, who manages more than $4 billion in assets for the bank's investment department. "There's safe in the context of buying the bond and holding it to maturity, or safe in what's going to happen to bonds between now and maturity. There's really no safe in the second scenario unless they're short-maturity bonds. You don't have any risk in U.S. bonds that are gong to mature in six months. You always know what's going to be at the end. In the middle, you don't have the knowledge."

That's because bonds, which promise to return an investor's principal at the end, can zigzag along the way and pay less than an investor put in if the investor decides to cash in early.

In the case of corporate or municipal bonds, investors might end up with a less-than desired amount if the bond issuer recalls the bond. Or, the investor may get nothing at all if the issuer is unable to meet its debt obligations.

Investors attracted to the high-yield bonds can avoid going it alone by purchasing a high-yield bond mutual fund. Or, they can enlist the help of a money management firm.

"We advise people to buy investment-grade bonds," Zerfoss said. "For our clients, as a general rule we only buy two of the three highest grades. We won't even go the lowest grade of investment quality bonds. We buy mostly AAA and AA bonds, although there are exceptions."

Hyman said most high-yield bonds are issued by medium-sized and small companies, but added that current market conditions make now a good time to buy some high-yield instruments.

"Many of these securities are priced so low the market is implying the economy is terribly weak," Hyman said. "I agree the economy is weaker than the Pollyannas on Wall Street are claiming in trying to calm investors fears, but it is not as weak as the prices and yields on many bonds imply. But let me qualify this by saying that not all high-yield bonds are worth buying. To the contrary, many are extremely risky and we would not be comfortable owning them. To separate the quality securities from the true 'junk bonds' takes a lot of work and understanding."

Bills and notes -- the securities the U.S. Treasury issues -- can be purchased in several ways. The easiest and least expensive way is via the government's electronic service, known as TreasuryDirect. How do I buy Treasury notes?

You can also buy them at banks and thrift institutions, brokerage offices and Federal Reserve banks. Private institutions generally charge a fee.

You can buy directly via www.treasurydirect.gov or (call 800) 722-2678.

-- Associated Press

BACK TO TOP |

Question: When is a telephone bond not a telephone bond? Mystery of the

telephone bondBy Dave Segal

dsegal@starbulletin.comAnswer: When the financial-services firm supplying the data makes a switch and doesn't bother to tell anyone.

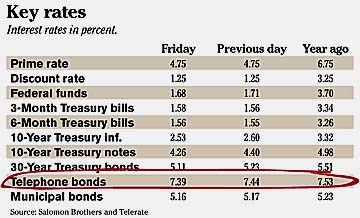

The New York Times News Service's daily key rates, which run in the print editions of the Star-Bulletin and are available for use by any of the Times' 600 full-service clients, carry yields for telephone bonds along with selected rates for government and municipal securities.

With the stock market meltdown, the so-called telephone bonds have been attracting increased attention from Hawaii investors because of yields listed at between 7 percent and 8 percent. As it turns out, though, the telephone bond yield the Times thought it was getting from data supplier Salomon Smith Barney is in actuality a callable bond from Virginia Electric and Power Co., a wholly owned subsidiary of energy provider Dominion Resources Inc.

The US West Inc. telephone bond that was the previous benchmark issue used in the Times' listings was replaced two years ago, according to Salomon Smith Barney spokeswoman Mary Ellen Hillery. However, that word never was passed along to the New York Times, she said."The bond put in its place is a comparable bond with a comparable yield," Hillery said. "It is a general (obligation) callable utility bond."

By virtue of being callable, Virginia Electric and Power is allowed to redeem the bond prior to its June 1, 2023, maturity if it determines the interest it is paying is too high for the current marketplace. If that happens, the company would repay the principal to the bondholder, plus a premium if it exists. Of course, the bondholder would have been getting periodic interest payments up until the time the bond was recalled.

Bob Hurtado, a Times business writer who in the past has dealt with Salomon Smith Barney's bond data, said the Times would be contacting Salomon to find out why that particular benchmark issue was chosen and why an electric utility bond was substituted for a phone bond. The key rates listing of "telephone bonds" also may have to be changed, Hurtado said.

Despite the confusion, Hurtado shrugged off the misunderstanding.

"It still gives the reader an idea of the high end of the yield market," Hurtado said. "It gives them a comparison about available issues."

The Virginia Electric and Power bond that the Times is using now has a 7 1/2 percent coupon, meaning it pays $75 per year on each $1,000 face-value bond, guaranteeing the bondholder a 7 1/2 percent return if it is held until maturity. Bonds, however, that are bought after the issuing date can fluctuate in the secondary market and offer different yields. The Virginia Electric and Power bond used by the Times closed yesterday with a yield of 7.39 percent.

Hillery said she was unable to determine the rating of the bond.

Bloomberg News, however, lists four bonds with 7 1/2 percent coupons and 2023 maturity dates.

Three are rated Standard & Poor's Corp.'s highest grade of "AAA," but the bond that most closely matches the listed key rates yield is rated "A," S&P's third-highest rating and two levels above noninvestment grade.

The bond also is uninsured, meaning a bondholder doesn't get his money back if the company goes out of business.

The replaced US West bond, which still trades, also has a 7 1/2 percent coupon and 2023 maturity date. US West was purchased two years ago by Qwest Communications International Inc., which currently is under a Securities and Exchange Commission investigation and is trying to stave off bankruptcy.