|

Got poi?

Neighbor island farmers struggle

to fight an apple snail invasion

ravaging their taro cropsBy Gary T. Kubota

gkubota@starbulletin.comNot as much as last year, some taro growers say, as apple snails multiply in the millions and gobble up their taro, the starchy underground stem that is pounded into the traditional Hawaii staple.

Buoyed by the recent flash floods, the hungry gastropods have multiplied faster than the farmers can sell them off as escargot.

"It's the No. 1 problem. A lot of farmers have been hit by apple snails," said Michael "Bino" Fitzgerald, a taro grower in Hanalei, Kauai.

Fitzgerald said his production has been down by a third, leaving him with a shortage of taro -- particularly last month during graduation luaus.

In the summer months, demand for poi is high while taro yield is low, and the snails have compounded the problem, he said.

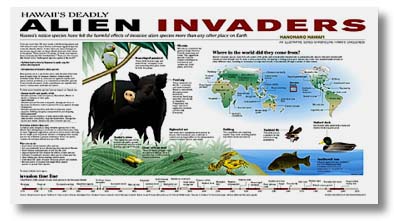

INVASION OF THE ALIENS

|

Originally from South America and introduced as aquarium pets in the islands, the snails were brought to taro farms on Maui, the Big Island and Kauai as a supplemental crop, said Harry Ako, scientist and apple snail expert at the University of Hawaii's College of Tropical Agriculture & Human Resources.Plans to raise them for sale as escargot backfired, Ako said. Farmers could not expand the escargot market, while the snails infested the fields and devastated the taro crop.

State officials releasing the snails into the wild in an effort to control weeds only made the matter worse, he said.

"They were considered innocuous at the time (in the early 1990s), but they are really invasive alien species," Ako said. "All you need is two, and at the end of the year, you are going to have 28 million. And it's impossible to kill them."

The snails are found on Oahu, Kauai, Maui and the Big Island.

On Oahu the snails have not infested the farms. But they caused serious damage to taro crops on the three neighbor islands, which together supply well over 50 percent of the taro for the state, Ako said.

|

The snails -- Pomacea canaliculata -- grow to the size of small apples and eat "everything" in the taro patch, Ako said. They are slow eaters, but because there are so many of them, they can devastate the farms.When farmers begin propagation by planting huli, or young stems from the taro plant, the snails munch on them at night and leave them lying dead in the field.

"You can't even get the thing started," Ako said, adding that the pests also devour the corms and leaves.

Many farmers have been picking the snails off their plants by hand, but the snails multiply faster than the farmers can pick them off.

"I cannot keep up with the snails," said Rodney Haraguchi, one of the largest taro growers in Hanalei.

Haraguchi said his production was down between 4 percent to 10 percent in the first quarter, and although his production has gone up since then, his work has become more difficult with the snail-picking chore.

|

In Keanae in East Maui, taro grower Solomon Kaauamo has trained ducks to eat the snails with some success. But Kaauamo said the ducks can only eat so many snails, and recently, stray dogs have killed many of his ducks.Na Moku Aupuni O Ko'olau Hui, a farming cooperative, has been buying apple snails from farmers in Keanae to sell as escargot, but the demand has been too small to keep up with infestation.

Cooperative official Awapuhi Carmichael said most hotels and consumers want the snails unshelled and prepared for cooking. The cooperative lacks a certified kitchen to prepare and sell unshelled snails, she said.

The demand for escargot is greater in Honolulu, Ako said, but farmers cannot ship them to Oahu. The state bans interisland transport of live apple snails, and farmers have no access to certified kitchens to prepare and shell the snails for shipping as escargot meat, he said.

Eradicating the snails would be an impossible task, Ako said, but there are methods to keep them under control. The farmers should limit the water supply, allowing the watery patch to turn muddy and thus fooling the snails into a dormant stage.

"They'll think, 'Oh, no, it's going to be dry.' So they'll go and hide in the mud, and when they are in the mud, they don't eat," Ako said.

Farmers also should use ducks to eat the snails -- but remember to keep the ducks in cages at night to protect them from dogs -- and hand-pick the snails off the plants.

No one method is guaranteed 100 percent, and the farmers must be vigilant, Ako said. The dogs will always attack the ducks, and humans can never pick off the snails fast enough.

"The farmers just got to get it in their minds that once they get the snails, they've got to do (all) these things. There's no way around it.

"You can wipe them out but they come back. You wipe them out again and they'll come back again" because the snails are efficient breeders, Ako said.

Ako used all these methods in the Keanae area in the early 1990s and helped the farmers double their yield three times in a row -- from 10,000 to 50,000 to 100,000 pounds.

The snail count in the Keanae area was 12 per square foot, but it decreased to 0.5 snails per square foot when he completed his eradication research, he said. However, the fast-breeding snails have returned in full force.

More research is needed but funding has been sorely lacking, Ako said. The college asked for $200,000 for taro research but received only $20,000 from the state Legislature two years ago. There was no funding for research this year.

The $20,000 was "almost nothing," Ako said. "It doesn't even pay for one half-time graduate student."

Ako has been experimenting with small doses of hydrogen peroxide, which affects the snail's skin.

"Basically, it fries them," Ako said, and the common household antiseptic apparently leaves no negative residues in the taro patches.

BACK TO TOP

|

The Poi Co. has baked its last poi cheesecake and dog biscuit. Business woes force

Poi Co. to shut its doorsBy Leila Fujimori

lfujimori@starbulletin.comKapiolani area resident Eddie Marcello says he misses the taro bread. Pearl Kong of Makiki loved the Poi Co. poi in bright green-labeled bags.

The company, one of Hawaii's largest poi manufacturers, is up for sale.

Craig Walsh and his wife, Marjorie, decided to cut their losses and closed the 10-year-old company in mid-May. "We never made a profit on poi, not a penny," Walsh said. "The only reason we survived was the $2.7 million of cash (they put into the company) and the other products."

Walsh blames the company's closure on poi's low profit margin, the lack of taro during the peak demand season, the cost of doing business in Hawaii and stiff competition in the poi market.

"We were very bullish on poi," Walsh said.

Poi represented 62 percent of the company's revenues The company sold 60,000 to 75,000 pounds a month on average, Walsh said, claiming the second spot behind the state's largest poi manufacturer, HPC Foods Inc., which distributes Taro Brand poi.

Walsh said a major factor in the closing stemmed from the seasonal shortage of poi due to greater demands from summertime parties and lower taro yields.

"Your one chance as a poi company to make a bit of money is to sell the product when the demand is high in May and June," he said. "Then, in a cruel twist of irony, you're cheated out of that because there's no taro."

Some see the Poi Co. as responsible for some of its own problems.

"They got too big too fast," said farmer Willy Kupuka'a, who had sold taro to the Poi Co. "He's making doughnuts, and he's not concentrating on his poi."

Star Market's poi buyer said the Poi Co. had problems keeping up with deliveries.

Caterer Monica Machado praised the company's baked goods. But she did not like getting the pre-mixed kind, which essentially meant paying for the added water.

The departure of the Poi Co. will leave a void, but Don Martin of the Hawaii Agricultural Statistics Service said other poi companies such as HPC may pick up the slack.

The Walshes acquired the company from Aimoku McClellan and his wife in 1997.

Walsh said McClellan left in 1998 to pursue other opportunities, though he kept a 5 percent interest in the company. "I never really wanted to be milling poi for the rest of my life," McClellan said.

He got into poi making after he started a home delivery service to Oahu's Hawaiian communities.

"They couldn't get enough poi, so we started making it in small batches," he said.

"We had a vision of trying to bring poi back as a staple, like rice is. We even tried to pay the farmers more to try to encourage the farmers to grow more. That worked to a degree, but the problem of taro supply was always an issue."

Poi's small profit margin, frequent deliveries and short shelf life put a strain on the company, and it "took a bloodbath on neighbor-island distribution" having to fly the product in daily, he said.

The public often complains about the high price of poi, Walsh said. While the company sold a bag of poi at $2.40 wholesale, stores sold it for $3.86. The manufacturers were stuck with having to pick up and pay for any unsold poi that soured.

He said the company did well when its product sold in warehouse store Sam's Club, however.

Compared with rice, poi is expensive, he said. For $4 a family can buy a 25-pound bag of rice, while a 1-pound bag of poi went for $3.59 to $3.86 in the stores, he said.

And he said the more affluent were more apt to buy poi, and his company sold more in Kahala than in Waianae.

"Poi seems to have a ceiling beyond which you can't sell it," he said. "If people don't want it, they don't buy it. They don't care if it's cheaper."

"It's not a business where you're going to make a killing overnight," McClellan said. "Poi is a low-margin business just by itself, and it's too bad it didn't work."

The company tried to subsidize poi with products having a higher profit margin, Walsh said, finding uses for sour poi in baked products.

McClellan knew diversification was the answer, but "didn't have the capital to take it there."

He credits the Walshes with putting in a lot of effort and coming up with creative ideas. Following the Poi Co.'s lead, competitor HPC began branching out, using poi in baked goods.

The Poi Co. saw a boom in its Internet freeze-dried poi sales last August after a tabloid touted poi as a diet aid. Walsh said the company sold 8 percent to 11 percent of products to Internet customers, more than sales through Times Super Market.

The company then turned to foreign taro. Last June, when the local supply was at an all-time low for the Poi Co., Walsh went to Western Samoa, where taro was cheap.

But the added air freight raised the cost to twice the price of local taro.

Customers, however, were not willing to buy the unfamiliar nut-brown poi over the usual purple poi. Those who sampled the product, however, liked its sweeter taste, Walsh said.

The cost of doing business in Hawaii, including governmental regulations, also contributed to the firm's demise, Walsh said.

Walsh's only regret in closing down the company was having to lay off 30 employees.

He said he has no plans for another business at this time and will return to his home in England.

BACK TO TOP

|

|

The average poi eater is about 52 years old and developed a taste for it when he or she was a child. And poi has shifted from being a daily staple to an occasional food item in Hawaii. Poi’s appeal slowly

rises anewBy Gary T. Kubota

gkubota@starbulletin.com"Those aren't encouraging demographics," said Kauai County economic development specialist William Spitz.

A study five years ago showed the traditional Hawaiian starch is not winning over the younger generation, but Spitz said he is optimistic the rising interest in Hawaiian culture may lead to a growing poi market.

"I would expect to see an upward trend," he said. "This Hawaiian renaissance may well spill over into the diet."

Waring Nakamura, sales manager for HPC Foods Ltd., the state's largest poi manufacturer, said his company has no statistics on the average poi consumer. But poi remains the company's most popular product with an apparently devoted following.

"Whatever we could make, we could sell. We could sell more if we had it," Nakamura said.

HPC has had problems getting enough taro for poi since Hurricane Iniki devastated Kauai, the state's largest producer of taro, Nakamura said. Despite weather, apple snails and other problems, taro production has been making a slow comeback for 10 years, except for seasonal shortages in the summer, he said.

The future of poi is promising, although it may never be as popular as rice, Nakamura said. His company, marketing its products under Taro Brand, has been finding ways to increase the consumer base.

"There was a point when we thought about getting into the school system to get more kids involved in eating poi," Nakamura said.

The marketing scheme was cost-prohibitive, but the company has found new consumers with poi-related products such as pancake mix, breads, cinnamon rolls, pies, mochi and poi powder.

"Poi is good for you; people are learning about the health benefits. We want to try to do more to educate the public," Nakamura said.

Poi and taro, spiritual foods in Hawaiian culture, are good for many babies who are allergic to grains and cereal, said Rae Mei-Ling Chang, executive director of the nonprofit group Hui No Ke Ola Pono, which operates Simply Healthy Cafe on Maui.

The cafe, located in the J. Walter Cameron Center, uses taro and poi in a low-salt and low-fat sugar diet as part of a continuing health study.

"It has a lot of fiber in it besides sustaining you with carbohydrates," Chang said.

BACK TO TOP

|

On the fertile plains of Keanae in East Maui, farmers are battling an irrigation company, apple snails and stray dogs in an effort to keep up with taro production. Maui farmers fight

numerous battlesBy Gary T. Kubota

gkubota@starbulletin.com"It's really hard to get everything going good," said taro farmer Solomon Kaauaumo.

Four to five years ago, he could harvest 1,000 pounds of taro a week from his patches of more than two acres, said Kaauaumo, whose family has been taro farmers for generations. Now the harvest is down to 500 pounds a week.

"We are hurting for water right now," Kaauaumo lamented. There isn't enough water in the streams to supply the taro fields, causing the taro to rot, he said.

The state is conducting a three-year study to determine the water flow for several streams, but in the meantime the farmers are locked in a legal battle with East Maui Irrigation for more water.

The farmers are asking the irrigation firm, a sister company of Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Co., to increase the amount of water left in the streams.

Misbehaving critters on the farm are not helping the situation either, Kaauaumo said.

Farmers imported apple snails to raise in the taro patches as a supplemental crop, but the slow-moving gastropods have devoured the taro plants.

The snails are sold as escargot to restaurants, but demand has not kept up with the growing number of snails.

The farmers then imported ducks as a solution. The ducks were supposed to eat the snails, which would have lessened the taro loss. But stray dogs attack the ducks, leaving snails to multiply and eat the taro.