Sparky On a dusty road in Kauai, a bunch of grade-school boys, mostly Japanese-Americans, raced up and down one day in 1924, then turned to playing dodge ball with a clump of rags knotted together because they were too poor to buy a ball. One lad kept coming in last in the races and was usually the first to be thrown out of the dodge ball game. Finally, an older boy laughed: "Hey, you slower than ole Sparky, the nag." Sparky was a hapless horse in the cartoon strip Barney Google and Snuffy Smith that invariably lost the races into which Google had entered him.

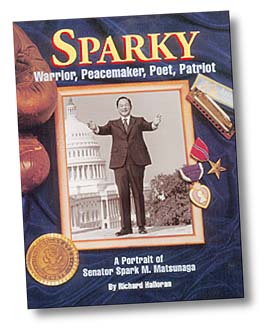

New book explores the life of Sen.

Spark M. Matsunaga, a Kauai boy

who helped a reluctant nation

accept its Asian-American brothers

Editor's note: This article was adapted from Richard Halloran's new book about the late Sen. Spark M. Matsunaga of Hawaii, titled "Sparky: Warrior, Peacemaker, Poet, Patriot," to be published by Watermark Publishing on July 12.

By Richard Halloran

rhalloran@starbulletin.com

|

The name stuck. Masayuki Matsunaga, through school, the University of Hawaii and Army service in World War II was Sparky to everyone. After the war, he had his name legally changed to Spark Masayuki Matsunaga because it would be more easily recognized in the political career he planned. Through his years in Hawaii's Legislature and the United States Congress, he was widely referred to as Sparky even if he was addressed as "Congressman" or "Senator." During Sparky's first term in the House, President John F. Kennedy either couldn't pronounce or remember the name Matsunaga as he acknowledged dignitaries on a platform in Honolulu. So the president addressed him: "My friend Sparky." Sparky was so pleased he wrote to a friend: "The president calls me by my first name."Along with Sen. Hiram Fong and Sen. Daniel K. Inouye, Sparky was a pioneer who made it possible for other Asian-Americans to be elected to Congress, to become governors and state legislators, and to be chosen for senior state and federal positions. They opened the way for Norman Mineta, the first Japanese-American to become a cabinet officer, as secretary of commerce in the Clinton administration, now as secretary of transportation for President George W. Bush. Elaine Chao, a Chinese-American, was the second, as secretary of labor in the Bush cabinet. Robert Matsui, another Japanese-American, is a U.S. representative from California. Gary Locke, of Chinese descent, is governor of the state of Washington.

|

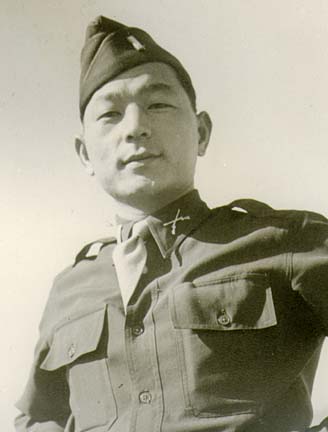

As a pathfinder, Sparky taught those who followed. Among the next wave of Asian-American politicians, Mineta was elected to the House in 1974. "I came to Congress knowing zilch," he said in an interview. "Sparky was just great. He was my big brother and I used to go to him every day -- how do you get recognized on the floor, what should I do about staff, where do I get office supplies, things like that. I considered him my mentor." Sparky had mastered the intricate parliamentary procedure of the House and one day a swift maneuver left Mineta puzzled. "What was that all about?" he asked. Sparky, who had an impish sense of humor, grinned: "If you had looked at Thomas Jefferson's manual on rules, you would have known."It all began during World War II, when Matsunaga, Inouye and thousands of other Japanese-Americans fought with valor against the Nazis on the battlefields of Italy and France, and as intelligence officers against Japan. Having proven their allegiance with their blood, they came home no longer willing to be second-class citizens. In Hawaii, many AJA's joined the Democratic Party and set out to wrest the Territory from Republican plantation and business owners, mostly Caucasian, who dominated the islands.

In the "Revolution of 1954," the Democrats won control of the Territorial Legislature. Inouye became majority leader and Sparky was chosen chairman of the Judiciary Committee in 1957. After Inouye had been elected to the Territorial Senate in 1959, Sparky succeeded him as majority leader. Sparky was deeply engaged in the struggle for statehood and after Hawaii became a state in 1959, sought to be elected lieutenant governor. He lost in the primary, the only electoral setback he experienced in 15 elections. He recovered in 1962 and was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. When Hiram Fong retired from the Senate in 1976, Sparky succeeded him. He remained in the Senate until he died on April 15, 1990.

|

Sparky was a distinctive politician, a man of many parts, some seemingly paradoxical. Spark Matsunaga was an American in every ounce of his being, and was proud to be an American. That sentiment underlay his public life. He was sometimes critical of his compatriots, notably about racial discrimination, because be wanted America to live up to its ideals. Fighting discrimination was a theme that ran through Sparky's political life in hopes of forging a better nation. As his longtime assistant, Cherry Matano, said: "Sparky was in love with America."Yet, like many second-generation Americans of whatever origin, Sparky retained a flavor of the land of his ancestors. As a nisei he had a facade, what the Japanese call tatemae, or "that which stands before," that shielded much of the real man. His interior, or honne, his "true feeling," was hidden and he was a very private man. Like most Japanese, Sparky disliked confrontation and tried to avoid the adversarial aspects of politics. He preferred what the Japanese call nemawashi, or "thorough preparation," in which he would seek the support of colleagues behind the scenes.

Sparky's style was evident when he sought legislation to redress the grievances of Japanese-Americans for having been unjustly incarcerated in "relocation centers" during World War II. His proposal would have the U.S. apologize to the AJAs and pay each survivor $20,000. In his nemawashi, Sparky approached each of the 99 other senators and persuaded 76 to be co-sponsors of the bill; usually two to 10 senators sponsor a bill. When the bill went to the floor, its passage was a foregone conclusion. The bill was also veto-proof, Sparky having pulled together enough votes to override a presidential veto.

A striking paradox arose from the differing perceptions of Sparky in Washington and Hawaii. In the Capitol, Sparky was immensely popular as most found him modest, even shy. He was the only Asian-American in the House in 1963, from a new and small state and yet was elected president of the freshman class of all newcomers. The former speaker of the House and later ambassador to Japan, Thomas Foley, said in an interview: "Sparky was one of the members everybody liked. He didn't have a congressional enemy. Someone like that can have tremendous influence and he operated across party lines."

Sen. Robert Byrd, the Democratic majority leader who became one of Sparky's mentors, said: "As a public official, he was modest in his manner and bearing. He envied no one, but he was ambitious in the interest of justice and humanity." Sen. Robert Dole, the Republican leader and presidential candidate, said in an interview: "Sparky would not make points at your expense in the newspapers, like some in both parties. He could be tough; you couldn't push him around. But he could move the process and not leave blood behind." A Democrat from Florida, Rep. Don Fuqua, said: "I don't know of anyone who did not like Sparky Matsunaga. You have to get along with people in Congress and you don't get things done by getting in their faces." Rep. Bill Frenzel, a Republican from Minnesota, echoed that view: "I never heard of anyone in either party who didn't like him. You could trust him."

In Honolulu, however, Sparky was not part of the Democratic circle around Gov. John Burns. Tony Kinoshita, a political campaign stalwart, said: "The Democrats hated Sparky." The late Sakae Takahashi, who had served with Sparky in the 100th Infantry Battalion in World War II, became a rival who declined to be interviewed before he passed away. "Anything I would have to say about Sparky Matsunaga," he said, "would be negative." Former Gov. George Ariyoshi noted that he and Sparky were considered outsiders. Robert Oshiro, who was influential in the inner circle, agreed: "Sparky was never part of the mainstream of the party." Rep. Patsy Takemoto Mink, whom Sparky defeated in the Democratic primary for senator, was cool in her assessment, contending: "Sparky stayed clear of controversial issues." Thomas Gill, a liberal lawyer who served in Congress with Sparky, found him unwilling to take stands in certain disputes. Judge James Burns, son of the late Governor Burns, summed it up: "Sparky was not a team player. He was on our side but he wasn't on our team."

Part of the criticism of Sparky appears to have been envy because he had risen to the highest reaches of American politics. Moreover, Sparky was a maverick with an uncommon style, a strong ego, and a touch of braggadocio that irritated some peers. A Japanese saying holds: "The nail that sticks up soon gets hammered down." Ted Tsukiyama, a prominent civic leader, said in an interview the Hawaiian concept of alamihi might be a better analogy: Alamihi is a black crab and, if one tries to climb out of a pail, the others drag him back. Those who would hammer Sparky or pull him down failed for a simple reason: Sparky was a proven vote-getter. In a couple of elections, he won with 82 percent of the vote; in American politics, 55 to 60 percent is a landslide.

In Washington, Sparky quickly became effective in looking after Hawaii's interests. Former Governor Ariyoshi said whenever he needed something done in Washington, "I always called Sparky and he always came through." In the office of Gene Ward, a Republican in the Legislature until 1998, the most prominent picture was that of Sparky. Asked why he displayed the picture of a political opponent, Ward replied: "When it came to serving constituents, Sparky Matsunaga was the best. I keep that picture up there to remind myself what democratic politics is all about."

Senate staff aides divide senators into show horses and work horses. "Sparky Matsunaga was definitely a work horse," said one. "He was an extrovert, like most of them, but he was not an exhibitionist." In the House, he was on the powerful Rules Committee, appointed by the speaker, John McCormack, who had become another of Sparky's mentor. In the Senate, Sparky attached himself to Senator Byrd, the Democratic leader for most of Sparky's l4 years there. Byrd made Sparky chief deputy whip, which Sparky relished because it engaged him in everyday parliamentary proceedings.

Sparky rarely drew attention in the national press because he didn't care. He was concerned only about his reputation in Hawaii because the voters there would decide whether he would be re-elected. The late A.A. "Bud" Smyser, one-time editor of the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, caught the differences between Sparky and Senator Inouye: "High national visibility has been a strong element in Inouye's success. Quiet, low visibility seems to serve Matsunaga equally well."

Like most politicians, Sparky loved being the center of attention. As Senator Inouye once said, with a laugh: "We are not humble people." Sparky's thirst was for personal, face-to-face, handshaking attention. He relished playing to an audience in the theater, on the campaign trail, or in Congress.

Even his impromptu remarks had the mark of having been crafted with words chosen for effect. Sparky was an accomplished raconteur and, like most politicians, was not above embellishing the facts if that made a better story. He once spoke movingly about a World War II battle as if he had been in it. That fight, however, had taken place after Sparky had been wounded and was far to the rear in a hospital.

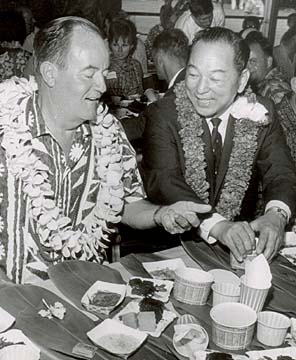

In giving his constituents top priority, Sparky became famous for taking to lunch nearly every visitor from Hawaii, be they bank presidents or sanitation workers. In the House or Senate dining rooms, he sometimes booked two or three tables and hopped between them. When those visitors got back home, Senator Dole said, "they became walking billboards for Sparky Matsunaga."

Richard Halloran is the former editorial director of the Star-Bulletin whose column, "The Rising East," appears weekly in the Sunday Insight section. He is a former New York Times correspondent who covered Asia and the military.