First Sunday

BY MARK COLEMAN

|

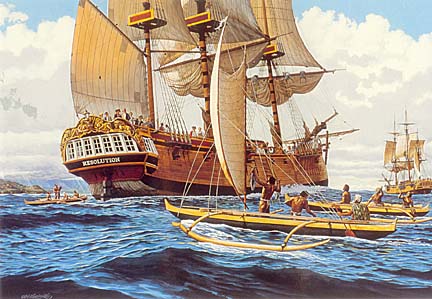

Reflection and researchHerb Kawainui Kane is possibly one of the finest and most important artists ever to emerge from Hawaii.

His carefully researched paintings, illustrations and sculptures have helped define our image of ancient Hawaii, while his research into Polynesian canoes and voyaging led to the creation of the sailing vessel the Hokule'a, probably the most important contribution to the Hawaiian cultural renaissance that began in the 1970s.

Kane's stunning, intricately detailed works can be found in museums, hotels, government buildings, and private collections, as well as in magazines, on album covers, on postcards, even on postage stamps. He has written and illustrated several books and contributed to many others. His latest book, "Ancient Hawaii," is a steady seller in bookstores and used as a textbook in local schools. As a design consultant, he has worked on resorts in Hawaii and the South Pacific, and on a cultural center in Fiji. He also has produced highly regarded aviation art.

|

Born in 1928, Kane was raised on the Big Island and in Wisconsin. He served in the Navy Air Corps, earned degrees from the Art Institute of Chicago and the University of Chicago, worked for many years as a commercial artist, then returned to Hawaii in 1970. At first he relied on his experience with architectural design to land work, but by 1980 he was painting full time.Kane used to be active in various community organizations and has been honored for his efforts with numerous awards. These days he lives somewhat reclusively with his wife, Deon, in rural South Kona and on Whidbey Island in Puget Sound, Wash. He no longer produces sculptures, but he continues to paint and write as the spirit moves him.

|

Herb Kane the artist

MC: When did you realize you were pretty good at drawing and painting?HK: When doting aunties started flipping over my childhood sketches, and other kids began asking me to draw fast cars and fighter planes for them.

MC: What kinds of things did you draw before you embarked on a professional career?

HK: In my student years I concentrated on that most interesting, variously complex and challenging of all subjects, the human figure. It's been said that one can learn to paint landscape or still life in a year or two, but the human figure demands a lifetime.

MC: I read some comments of yours regarding representational art, and I loved your point about taking the artist's ego out of the image. Would you agree, however, that even in representational art, individual style emerges? Your artistic creations, after all, are almost impossible to miscredit. Is it because of how you use colors? How you portray the human form? Your focus on certain subject matter?

HK: All of the above, but individual style just happens and will reveal itself to others like the sound of a voice or individual handwriting. Many artists, particularly the youngsters, fret about style. Fearing to do something that's not in vogue, they do nothing. Artists should not worry about their individuality; it shows in their work just as in their penmanship.

MC: What is the medium you use for most of your paintings?

HK: Oil and alkyd resin paints on gesso-grounded linen canvas.

MC: The paintings in your earlier book "Voyage, The Discovery of Hawaii" (as excerpted in "Voyages") seem somewhat impressionistic. Your later paintings appear sharper. Is the change a reflection of how your art has matured or evolved?

HK: I used acrylics for the art for the book "Voyage." Acrylics dry quickly, allowing the work to move forward quickly. The larger body of work has been done in oil and alkyd, vastly lengthening the time required for the painting, and allowing for more reflection, deliberation, and perhaps ultimately more refinement and detail.

MC: I don't recall seeing any paintings by you of Hawaiian monk seals. Did I miss those?

HK: No paintings of monk seals.

MC: Why not? Did they not figure into ancient Hawaii that much?

HK: I've never seen or heard of monk seals in Hawaiian traditions, and I cannot explain why that is because they must have been much more prevalent in earlier times than they are now. My home island being the farthest removed from those frequented by monk seals is another reason for them being beyond my horizon.

The Hokule'a

MC: How did you learn the skills to become one of the first captains for the sailing canoe Hokule'a?HK: Sailing multi-hulls and racing catamarans. Also, knowing that I was the general designer of Hokule'a, from the moment we launched it everyone looked to me for sailing instruction. So I was an unelected default captain.

MC: Where did you learn to sail? In Wisconsin? Hawaii?

HK: My first sailing experience was as an 8 year old. I was living in Hilo, but Dad liked to go to Kona for fishing. I went out with an elderly fisherman one day. After hand-lining his catch, he unrolled the mast and sail and set up the mast and told me to get out on the forward 'iako (the boom connecting the canoe hull to the outrigged float). Then he trimmed the sail to the on-shore breeze and the canoe took off. It was like being on the back of a bird.

MC: Did you learn about how Hawaiians constructed their sailing canoes by trying to paint them historically accurate? What sources did you consult?

HK: I learned some things first hand, a great deal from the study done by Haddon and Hornell ("Canoes of Oceania"), accounts by early European witnesses, visits to museums, and correspondence with museums throughout the world. Next, I assembled my findings in architectural drawings. Step three was a series of paintings depicting some sense of the presence these vessels must have had on the open sea with people on their decks. The first 11 of the series was purchased by the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts as the "Canoes of Polynesia Collection," and (then-)Lt. Gov. George Ariyoshi hosted a show at the state Capitol. This was soon after I moved to Honolulu from Glencoe, Ill., and the show brought together persons interested in the idea of taking the next step, which was building a replica and putting it to test.

MC: Do you think the Hokule'a has outlived its usefulness, and now is only inviting a disaster through its continuing voyages?

HK: Not at all. The whole idea was that it should continue to serve as long as possible. Right now it is going through major refurbishment and her human company are an entirely new generation, with wonderful enthusiasm. What we did not expect was that this canoe would make such a significant impact throughout Polynesia. An estimated 20,000 met the canoe on the beach at Tahiti. Canoe building and voyaging took off in the Cook Islands and New Zealand, and canoes were built in Tahiti, Samoa, and other islands, converging on Rarotonga in 1992 when the South Pacific Arts Festival was held with the theme "canoes and voyaging."

None of us had any idea in the beginning that our message would resonate as it did across the Pacific, across international boundaries. The voyaging canoe became recognized as truly the space ship of our ancestors, without which there would not have been a Polynesian people. By the demands it made on those who ventured out in it, it symbolizes those qualities our Polynesian ancestors must have had in order to survive and succeed, qualities we would do well to emulate today.

John Webber

MC: How much have you relied on drawings of Hawaiians by early European visitors to the islands? Which of those illustrators do you think was the best?HK: As a sailor I could tell which drawings were accurate. Some drawings of canoes were wildly inaccurate, incompatible with the written records, and this led me to search for their true design. The best of the early European artists was John Webber, with Captain Cook.

MC: Why was Webber the best?

HK: He had the best "eye."The influence of his training and ideals showed, but as a reporter of what was seen, I feel he was way better than Hodges, Buchan, or any of the others. Parkinson can't be beat for his drawings of flora, but Webber could draw anything.

Motivation

MC: Why you care so much about Hawaiian history?HK: My Hawaiianess is why I care. But that's a cultural thing, because my dad cared about it even though he preferred to live in a small town in central Wisconsin, especially in his later years, making only occasional visits to Hawaii. Like my dad, I am not nostalgic about any "good old days" in Hawaii. All peoples romanticize their pasts and Hawaiians are no exception. I don't subscribe to that type of "Hawaiianess" or to the type that wants to revive the monarchy or anything else that produces attitudes that obscure our view of history.

Herb Kane the writer

MC: When did you realize that you were a good writer?HK: I'm not a good writer. Writing is always a sweat for me. I worked with some very good, highly disciplined writers in advertising and publishing and learned from them. Also I took a couple writing classes at the University of Chicago where I picked up the academic credits I needed for my bachelor's and master's degrees.

MC: I really like the Hawaiian pronunciation guide that you included at the beginning of your "Ancient Hawaii" book. That is about the clearest guide on the subject I have ever seen.

HK: Mahalo. Major credit should go here to Kalani Meinecke, head of Hawaiian Studies at UH-Windward.

MC: I may have overlooked it but I haven't been able to find any reference in your books to the fact that the ancient Hawaiians practiced human sacrifice.

HK: Page 34, paragraph four in "Ancient Hawaii": "Of all the spirits, only Ku merited that most precious gift, the life of a man, and only the king could order it." I think that accurately describes the concept and places it within its social framework. The term "sacrifice" is a misnomer. "Gifting" is more appropriate. The higher the status of the recipient, the higher must be both the status of the giver and the value of the gift. This status ladder is completely overlooked by writers who dwell on bloodthirsty orgies of "human sacrifice" to engross their readers. Missionaries, arriving after the practice was abandoned, and for their own reasons, seized on "human sacrifices" as a great fault of those who they had come to save.

MC: I wonder, too, whether you may have put too happy of a face on how ancient Hawaiians regarded their payment of taxes. You say in "Voyages" that Hawaiians considered their taxes "gifts that brought honor to the giver, and obligated the ruler to provide justice and security." But, really, was there never any individual or organized resentment against such impositions?

HK: Some of the old stories suggest that some rulers taxed too heavily. Working off the tax-gift obligation was a way to get public works done; I should have mentioned that. On the other hand, we know that when some of the ruling class traveled, they would be met with mountains of gifts, much of it in craftswork but much also in foodstuffs which they in turn would distribute back to the people for a feast. This went on well into the monarchy.

MC: On the subject of the changes that occurred after the death of Kamehameha in 1819, you make it sound like the kapu system was abolished for geopolitical reasons (page 39, "Ancient Hawaii"), which makes sense. But I have heard it told that in many respects it was a women's liberation movement, revolving, of course, around the tabu forbidding women to eat with men and to partake certain items of food and drink. But it couldn't happen until after Kamehameha died, because he was so stern and ruthless.

HK: Geopolitical reasons, yes. Also, the observation that Europeans not only had superior or more interesting materials (metal, gunpowder, glass, woven cloth, whiskey) but that they also survived diseases that were slaying huge numbers of Hawaiians. These made it seem obvious that the European God was truly more powerful and beneficial than the Hawaiian akua, to whom the kapu system was dedicated.

The future

MC: What are your plans for the future?HK: Plans? At my age you just hope to get up tomorrow. I'm 74 ... Like everyone else my age, I cannot believe it all went by so quickly, and with so many friends having dropped off the twig, I can't believe my luck in making it this far.

BACK TO TOP

|

Reflection and

research guide

Kane’s approachThe "books" Herb Kane has read most recently provide insight on how an artistic commission develops and how he tackles the subject matter. They include the journal of Lord Byron, cousin of the poet and captain of the frigate Blonde; and the journals of three who traveled with Byron: James Macrae, a botanist; Andrew Bloxam, a naturalist; and Robert Dampier, an artist.

Herb Kane: A California couple bought a small painting at a local gallery, then decided they wanted me to do something larger. As a girl, the woman remembered following her dad when he went for opihi around Hilo Bay, and thought a painting of Hilo Bay would be nice. I wasn't interested, but after some reflection, I suggested ... a painting of the bay when, in 1825, the first ship of some consequence was anchored there -- the 46-gun frigate Blonde, which had returned the remains of the king and queen of Hawaii after their deaths in London.

Both Cook and Vancouver had passed the bay to avoid its lee shore, but Byron's first lieutenant took soundings and found the long "reef" of lava that encloses and protects much of the bay. (Today, the long breakwater is built on it, and it is still on the map as "Blonde Reef.") Byron saw it as a fine site for wood, water and provisions to refit the ship for the journey back to England. The Queen Regent, Ka'ahumanu, entertained him, and ordered that Hilo Bay be forever called Byron's Bay.

I decided to do a painting of the moment of departure. The idea was cleared with the clients.

In a very rough preliminary sketch, the view of the bay is from the northern shore of the little islet that even at that early date had received the name Coconut Island. Men and boys are picking opihi from the rocks. Part of a thatched house in a grove of coconut and milo is seen at the left. A small fishing canoe is being paddled in from the right. This foreground area is in cloud shadow.

In the middle ground, in bright morning sunlight, the frigate, surrounded by canoes and a schooner, is ghosting out toward the channel. The view is from the starboard quarter, the sails braced around to pick up any breeze.

In the distance, rising from a low cloud bank and shadowed green flanks, the summit of Mauna Kea flashes white with snow. Because this was in mid-July, I had resigned myself to showing Mauna Kea without snow, until I read James MacCrae's journal. MacCrae wrote that Mauna Kea had a snow cover...

Now the remaining question was the exact appearance of the Blonde. Dampier's drawings and two paintings of the ship informed me about the sails and spars, but were lacking in detail on the hull. I found that the National Maritime Museum, in Greenwich, England, now has a Web site, and one can engage the services of a researcher there. I was about to get in touch with them when a visitor came who could give me better assistance.

I had met Dame Anne Salmond when she had visited Hawaii earlier. A professor of history at the University in Auckland, she is also the author of two books about early contacts between Maori and Europeans. (During a visit from her and her husband while on a world tour,) she learned of my interest in researching the frigate Blonde, and that I was about to send an e-mail to Greenwich. She said, "I'll be there in five days and I'll search for you."

Naturally, I was pleased. My request would be presented to the museum staff by a dame of the British Empire, far more likely to get the staff's full attention than an e-mail from a nobody half a world away.

Later, she sent and e-mail that began, "Eureka!" and went on to say that they have the original plans on file. The copies of the plans arrived last Friday.

Mark Coleman's conversations with people who have had an impact on our community appear on the first Sunday of every month. If you have a comment or suggestion, please send it to mcoleman@starbulletin.com.