|

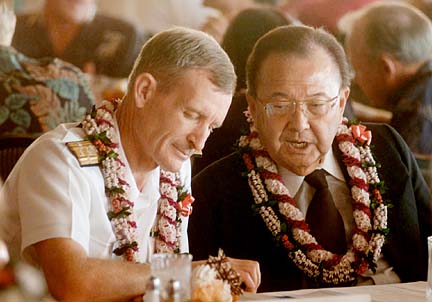

Blair had unique As Adm. Dennis Blair looked back over his three years and three months as commander of U.S. forces in Asia and the Pacific and America's proconsul in the world's most troubled region, his thoughts ranged over:

style of leadership

As the Pacific commander says

aloha to the islands, he reflects

on his mission, his methods and

how Sept. 11 affected them bothBy Richard Halloran

rhalloran@starbulletin.com

>> America's prickly relations with China;In preparing to relinquish command on Thursday, Blair also talked in an interview about his personal style of leadership. His approach has been marked by persistence, a nurturing of advice from subordinates, a surprising cultivation of the Asian and American press and public addresses that have sometimes been plain spoken and other times eloquent.>> His disappointment with Japan until last Sept. 11;

>> The promise of expanded military collaboration with India;

>> The slow but hopeful pace of reconciliation with Vietnam.

Blair doesn't much care for the term proconsul with its Roman connotations of political governance. "I've always felt that my real job is to direct the armed forces of the United States in this part of the world," he said.

"That's what I do that nobody else does."

At the same time, he acknowledged that he is the only American in this region who can speak for the United States to the leaders of all Asian and Pacific nations. In contrast, an ambassador can speak only to the nation to which he is accredited. "I have the responsibility to talk about things from a regional point of view," Blair said. "That makes what I talk about wider than what an individual ambassador can talk about." He has visited about 40 nations during the past three years.

It's easy to lose sight of the immensity of the Pacific Command's area of responsibility, which runs from the West Coast to the edge of East Africa.

Within its boundaries operate the world's six largest armed forces, including 300,000 American soldiers, sailors, marines and airmen who are equipped with, among other things, 190 warships and 400 combat aircraft.

Adm. Thomas Fargo, currently the Pacific fleet commander, has been nominated to relieve Blair. He will inherit the task of dealing with threats of war between China and Taiwan, between North Korea and South Korea, between nuclear armed India and Pakistan, and competing claims that may jeopardize vital shipping lanes through the South China Sea.

A resurgent China has been high in Blair's priorities. Only a couple of weeks after he took command in February 1999, he set the tone for a strategy balanced between deterring and engaging the Chinese.

|

In testimony before Congress, Blair gave two reasons for military exchanges with China. First, when Chinese officers see American soldiers or sailors training, he said, "they learn how good they (Americans) are." He said those visits were intended to teach "the Chinese what sort of capability we have."Second, he said, they see "we're not sitting here dying to pick a fight with China." At the same time, Chinese have been told the United States is prepared to fight if it must. The basic message, Blair said, is "Don't mess with us."

His strategy was tested a year ago when a Chinese fighter hit a U.S. EP-3 reconnaissance plane, forcing it to make an emergency landing on the island of Hainan. Blair noted that those intercepts had become more dangerous in the preceding months, but the Chinese had ignored American protests.

"It is not normal practice," he told the press dryly, "to practice playing bumper cars in the air." Under steady pressure from the Pacific Command, the American embassy in Beijing and Washington, China eventually released the crew, and later sent the plane home.

In the next few years, Blair said in the interview, "I think China will still be trying to figure out just what its role is going to be with its neighbors. Is it going to try to bully them? Or is it going to accept the sort of soft power that comes from being an economically dynamic and regional power?"

Critics of Blair among right-wingers in Washington have asserted that he should have taken a harder line with China. Blair seems unperturbed by the allegation.

Turning to Japan, often referred to as the "linchpin" of U.S. security in Asia, Blair said: "If it had not been for what I've seen after 9-11, it would have been a disappointing three years in the relationship with Japan."

Many observers have pointed to the political paralysis, economic doldrums and passive pacifism gripping Japan for a decade. Blair said Japan- ese leaders were concerned with trivial issues, even when talking with the president, that should have been handled by mid-level officials. "Our relationship was no more than a collection of individual friction points in our basing relationship," he said.

"Then 9-11 really was a step forward," the admiral said. Japan came up with naval and air logistic support for U.S. operations in Afghanistan, political support in the international arena and promises of economic help in rebuilding Afghanistan. "So I'm feeling good because now I see our leaders talking like leaders talk."

With India, the admiral said, "a cold-blooded calculation" showed that "India and the United States are on the same side on virtually all issues."

He foresaw more cooperation "directed toward things that are important to both of us," such as peacekeeping, military exercises, security of the sea lanes, and countering terrorism and drug smuggling.

About Vietnam, Blair said. "The most interesting part of my trip (in February) was my meeting with General Giap." Vo Nguyen Giap, 90 years old, led the Vietnamese army in its successful fight against France after World War II and later against the United States. He is considered to be a leading authority on guerrilla war.

Blair said Giap thinks Vietnam's "future is in connections with the West, and not only economic connections but human connections." He said Giap wanted to be known as a wartime general who now saw himself as "a general of peace."

The role of the commander of the Pacific forces has evolved during the last 20 years as the demands of security have changed and each has sought to leave his imprint on the command. In general, the duties of proconsul have become more prominent, especially in combating terror.

Blair, who was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford in England after graduating from the Naval Academy, is a tall, lean, reserved man with an understated Scottish sense of humor. He tells about a Scot who forgot his bagpipes in an unlocked car and returned to find two more left by pipers getting rid of them.

Asked what was the most important lesson learned during his watch, Blair paused for a long moment. "I guess I've learned the importance of persistence," he said. "It's a case of knowing where you want to go and, as opportunities present themselves, you take advantage of them."

He had persisted in trying to persuade nations to work together on common missions, an effort that sputtered until Sept. 11. "The biggest example of having been persistent over three years was this idea of working together against common threats," he said. "And then a big one came and we were able not only to make advances in cooperating but to go against terrorism in our theater very quickly."

Part of Blair's persistence has been to explain his thinking through the press, a tactic many senior military officers avoid. "If you have a good policy you believe in, you need to get the word out," Blair said. "The traditional barriers between your internal audience and your external audience are blurred now. Everybody reads the same thing."

Moreover, as lines between foreign and domestic presses have crumbled, Blair said, "you have to be consistent in what you say." Since Sept. 11, Blair has met the press in Hong Kong, Manila and Zamboanga in the Philippines, Tokyo, Hanoi, Kuala Lumpur and Kota Kinabalu in Malaysia, Singapore, Jakarta and New Delhi as well as making appearances on CNN, National Public Radio and other American news outlets.

At his headquarters, Blair has been considered a demanding taskmaster who set high standards but patted people on the back when they accomplished their tasks. He formed teams to work on a project to cut down on intrastaff rivalries but did not care for consensus at the lowest common denominator.

He encouraged the staff to speak up, something not all senior military officers do. "You take time to get input, and contrary input is often the most valuable right at the time you have to make a decision."

Said a staff member: "Comments from the back row were genuinely encouraged."

There was no question, however, about who made the decisions: "I'll say OK, I've got it, I understand everything you've told me, now here's the decision."

The hardest decisions were to send people into harm's way, which was harder than leading them into danger yourself. "Most people understand it in terms of their kids. When your kids are going through something tough, you'd much rather do it yourself, but you can't. You just physically can't do it for them. It's very much like that when you send your forces in."

Each time he orders forces into danger, Blair said, "I write a very careful document to my joint task force commander that spells out exactly what his mission is, and then I give it to him and say, 'Can you do this?'" Those commanders often said, "Most of it looks about right but here's something I'd rather have another way." Blair said, "Some of it I changed, some of it I didn't."

If commanders do their jobs properly, Blair said, "your people don't have to be heroes. Heroism is generally the difference between what the senior officer thought was going to happen and what actually happened when he sent the people into that mission."

In public speaking, Blair prefers to be plain spoken with occasional excursions into eloquence. At a candlelight memorial service in the Punchbowl after Sept. 11, he said, "We will light our many candles and we will drive out the darkness that is terrorism."

"If there is any doubt about the determination of America to accomplish this, look around you tonight," he continued. "The spirit of Pearl Harbor has been awakened here and throughout the nation. And we will prevail."