|

Immediately following the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, the Imperial Navy's submarines RO-13, RO-64 and RO-68 used their deck guns to shoot up "enemy flying-boat installations" on Howland and Baker islands near the equator, south of Hawaii.

During the opening moves

First of two parts

of the Pacific War, dozens

of Kamehameha students

were rushed into the breechBy Burl Burlingame

bburlingame@starbulletin.comWhat they actually shot at were shacks manned by Hawaiian teenagers, there because of a bizarre territorial dispute that had erupted six years earlier.

Pan American Airlines had plans to pioneer air travel across the Pacific, and in 1935 came to an understanding with the U.S. government: It would establish refueling bases on remote atolls for its short-legged flying boats with help from the U.S. Navy. The Navy agreed. The agreement gave it an excuse to establish hegemony over far-flung areas of the Pacific, a concept essential for countering suspected Japanese buildups in the mandated islands.

Bill Miller, director of the Bureau of Air Commerce -- a single desk within the Department of the Interior -- came up with the idea of colonizing uninhabited atolls known as the Equatorial Line Islands, sun-blasted guano heaps called Jarvis, Baker and Howland. The islands had been claimed by the United States according the Guano Act of 1856, and had been steadily mined of bird droppings for 20 years. Phosphates gleaned from the droppings were turned into explosives. Americans abandoned the islands in 1877, and the British briefly inhabited them before they, too, left them to the seabirds.

|

By the 1930s, both countries were competing for air routes, and the Equatorials, almost halfway between the United States and Australia, once again looked promising. In Hawaii, Miller sprang the colonization idea on Albert Judd, a trustee of Bishop Estate. Judd suggested that boys from Kamehameha Schools would be ideal candidates for settlers.The Hawaiian background of these boys made them excellent pioneer material, claimed Judd. He pointed out that they were used to hot weather and living off the sea, and were disciplined by years at a private school in which ROTC was a requirement. Miller was sold, and the operation began in 1935.

England got wind of the plan and rushed her own settlers to the islands, using New Zealand as a stand-in. Lt. Harold A. Meyer of the 19th Infantry, who advised Miller on military aspects of the settlement, made the extraordinary step of telephoning Washington directly from Schofield Barracks. In a two-hour phone call, Meyer begged for swift action.

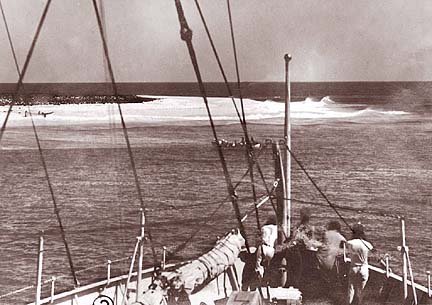

Meyer was placed in charge. Within the day, March 20, 1935, the Coast Guard cutter Itasca was outfitted with supplies and Hawaiian settlers, and raced off for the Equatorials. Lt. Cmdr. Frank Kenner, skipper of Itasca, later recalled that the little cutter never made better speed.

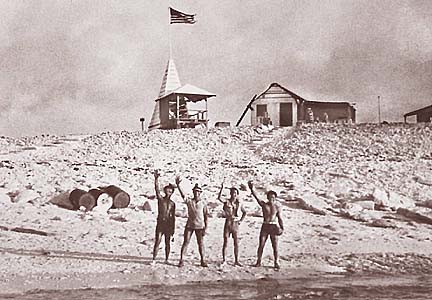

The Hawaiians had no clue as to their destination. Nor did the dozen or so soldiers who accompanied them. They had been told simply that it was a security matter. Despite a scare when the ship spotted another vessel and a brief stop at Palmyra atoll to dig up some palm trees for transplanting, the Hawaiians and the soldiers managed to raise the American flag first on the contested atolls.

|

Every six months or so thereafter, depending on the availability of Itasca, four boys were deposited on each of the three islands. By the time of the Pearl Harbor attack, some 135 Hawaiian teens had participated in the settlement."When we were invited to participate, there was a rush of applicants," recalled Abraham Piianaia, one of the first recruited. "They only wanted graduates, and for boys right out of high school, at the height of the Depression, the $3 a day they paid was good money." It was more than the salary of the soldiers who were rotated off the islands after a few months, leaving the boys alone.

At first the Hawaiians lived in pup tents, eventually graduating to wooden shacks dubbed "Government Houses," which were open on the sides to let the cool night breezes blow through. All fresh water had to be brought to the islands. The 50-gallon water drums were too heavy to boat to the shore, so each was dumped over the side of the supply ship and allowed to drift ashore. If the drums landed on the wrong side of the island, the boys walked across the island to get a drink. Whenever it rained, open containers on the island were set out.

Jarvis Island, nearly 1,000 miles east of Baker and Howland, had a ghost town still standing, testimony to American and British guano miners of the previous century. A 25-foot-high sign still read "The Pacific Phosphate Company of London and Melbourne." On the beach was the wreck of the barkentine Amaranth, which provided lumber for furniture, shacks and surfboards.

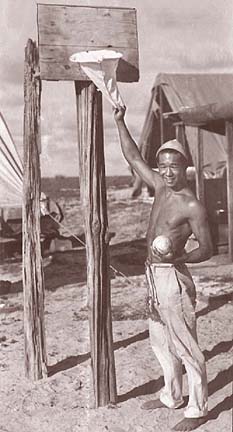

The settlers' main tasks were logging hourly weather reports, clearing land for a runway and servicing a small lighthouse. They also collected wildlife samples for the Bishop Museum of Honolulu. Otherwise, it was very much a Robinson Crusoe existence on the islands, which rose barely a dozen feet above the sea. Responsibility for the project was transferred to the Department of the Interior. Meyer's involvement was remembered in a bilIboard-sized sign, which declared Baker's few buildings to be the town of "Meyerton."

In the opening days of 1937, Howland Island was suddenly taken over by Navy engineers, who put in a short airstrip. The runway was built in anticipation of Amelia Earhart's planned 'round-the-world flight. When Earhart cracked up her Lockheed on the runway at Luke Field in Pearl Harbor, while taking off for Howland, the flight was rescheduled for the summer.

Earhart next tried to fly around the world in the opposite direction. On the leg between Lae, Papua New Guinea, and Howland, her aircraft disappeared, the last radio signals being picked up by Itasca, which had paused along her route to give bearings. Earhart and her aircraft vanished despite a massive Navy search. A shower and private bedroom the Hawaiians had built for Earhart went unused. They grieved for her and built a 20-foot sandstone monument, which they called the Amelia Earhart Lighthouse.

Things were quiet for the next few years, marred only by the death of a colonist in 1938 of peritonitis brought on by appendicitis. Coast Guard cutter Taney traveled 1,310 miles at full speed to save the boy, but arrived too late.

Canton and Enderbury islands were added to the program the same year, and were the subject of an exchange of notes between the United States and Great Britain in 1939, the upshot being an agreement to joint administration for at least 50 years, after which the agreement could be extended indefinitely. Each government was to be represented by an official, and the islands were to be available for communications and airports for international aviation -- but only of American or British-empire airlines.

Similar circumstances prevailed at Christmas Island, under the administration of the British high commissioner of the Pacific, headquartered in Suva, Fiji. America claimed a seaplane base there, as both countries claimed sovereignty based on occupancy. Britain, however, controlled the island from the end of World War I to 1941. Johnston Island, actually a string of islets that were technically part of the Hawaiian Sea Frontier, was under sole jurisdiction of the United States. All the islands were prized solely for their location.

The Kamehameha students serviced the islands' meager facilities, and spent the rest of their days fishing and working on their tans. "Lobster every day, which we ate raw," said Piianaia. "And the island had these big rats, which ate the pili grass. Vegetarians. We used to catch them and roast them for red meat. They were delicious!

"We were paid our salary in a lump sum when we went back to Honolulu, and it was quite a bit of money. We let our hair and beards grow long; it made us feel like explorers. But as soon as we went home, we hit the barber shop."

At night, the bowl of the universe blazed above the isolated atolls. Falling stars were so bright they'd cast shadows. One night, the waters roiled with hundreds of porpoises, a pod that seemed to stretch to the horizon. Some evenings were reserved for ghost stories, punctuated by the sound of birds crying eerily in the darkness.

There was magic there.

Tomorrow: A rescue mission to the South Seas.

Portions of this story are excerpted from "Advance Force -- Pearl Harbor" by Burl Burlingame, Naval Institute Press, 2002. BACK TO TOP

|

The Bishop Museum will present "The Panala'au Years: Hawaiian Colonists of the South Seas 1935-1942," running May 18 through June 16. The museum-designed "traveling exhibit" tells how young Hawaiian men occupied remote, uninhabited islands in the equatorial Pacific. The exhibit includes oral histories, photographs, artifacts and programs. Information: 847-3511. Panala'au exhibit