|

Old salts gather The U.S. SeaLab program in the 1960s was considered a failure because some of its activities were so highly classified no one knew about them until recently, says the Honolulu submarine specialist who headed SeaLabs II and III.

to recall Navy’s

secrets of the deep

A Navy veteran talks about his

time in the SeaLab programBy Helen Altonn

haltonn@starbulletin.com"I had five or six programs going," said John Craven. "One was multiheaded, so highly classified that nobody on it could tell relatives or anybody. They couldn't even speculate who else was involved in the program. It was a special top secret program, which meant it didn't exist."

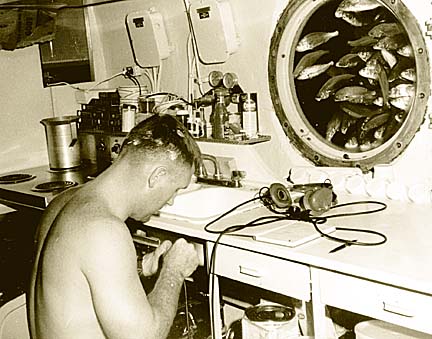

Three SeaLab habitats were developed to house divers for weeks on the ocean floor to prove they could live and work on the sea bottom.

SeaLab participants still can't discuss much of their classified work, Craven said, but some details were revealed in "Blind Man's Bluff," a 1998 account of Cold War submarine espionage.

Craven, who was the Navy's chief submarine scientist, also has written a book, Silent War," on his experiences.

He was among dozens of veterans of the deep submergence program recounting their achievements during a gathering earlier this month in San Diego, an event that takes place every other year.

Craven said he was not involved with SeaLab I, which was lowered off Bermuda's coast in 1964 to test "saturation diving," using a mix helium and oxygen to allow divers to go to greater depths.

But when the program moved to San Diego, Craven said he was "the Grinch who stole Christmas." He had been chief scientist of the Navy's Polaris Program, then headed the Deep Submergence Project that followed. He was suddenly put in charge of the SeaLab program when it was moved from the Office of Naval Research to the Navy's deep submergence group, he said.

"I couldn't even snorkel at the time and here I was taking charge of a program that was going to put men in the deep ocean." (He later learned to do deep sea diving.)

Craven started a classified program to go to the bottom of the ocean and pick up objects on the deepest sea floor.

"The purpose was to provide the Navy with the capability of essentially locating and picking up from anywhere in the ocean anything of military significance. That included atomic bombs.

"This program eventually was the major program that won the Cold War," he said.

SeaLab II was built in 1964 and lowered 205 feet, deep off of San Diego in 1964. SeaLab III in 1969 was the most ambitious habitat and the most secret, testing a system that would let divers leave a submarine, walk on the sea floor and retrieve objects, Craven said.

"We had an unfortunate accident. A diver dies. When that happens, the whole Navy and the world believe saturation diving doesn't work."

Diver Berry Cannon died after going down wearing equipment that lacked the chemical needed to remove carbon dioxide.

The program was taken from Craven and set up with limited funds for experiments in Panama City, Fla., but that did not end his underwater work, he said.

"Now, we immediately start a program in the deepest, darkest, secret black area. That program goes on completely unknown until a couple of U.S. Navy traitors revealed to the Soviets that we've been out there using saturation divers to tap their telephone cables."

The USS Halibut, a specially designed submarine, used work from SeaLab in 1971 to send divers to the depths of the Soviet Sea of Okhotsk to retrieve Soviet test missiles. They also installed a tap on a phone cable that gave U.S. intelligence officials an inside look at the Soviet Navy.

"No one really paid attention until 'Blind Man's Bluff' came out," Craven said.

All of those involved with the deep submergence vehicles over the years, who were never able to get together, began showing up at SeaLab III, he said.

Among those at the reunion of submarine veterans this month, Craven said, was Anatoly Sagalevitch, "the John Craven of the Soviet Union." Craven said he visited Sagalevitch's ship when it came here once and the two maintained contact through the years while the countries competed for undersea capabilities and intelligence.

Craven left the SeaLab program in 1970 but stayed on for a time as a member of the Defense Intelligence Agency's science advisory board.

Now he reviews proposals for the Defense Advance Research Project Agency to keep himself technically up to speed, he said, and he is still connected with the Navy and Defense Department on unclassified projects.