Sunday, December 16, 2001

|

Breaking up There are certain things Paul LeMahieu says he will not do. One is to point fingers or assign blame. He repeats this mantra through nearly four hours of conversation over three days. He cleaves, instead, to the word "responsibility."

is hard to do

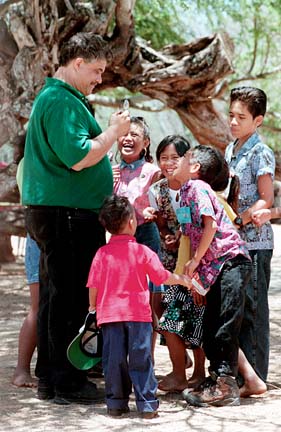

Paul LeMahieu seeks to fit

together the pieces of the puzzle

that was his tenure as head of

Hawaii's public schoolsBy Cynthia Oi

coi@starbulletin.comMere semantics, some may argue, but LeMahieu has a lot to say about the responsibility of the legislative committee and the state auditor in their investigations of the cost of the special education and about their roles in the turmoil that led ultimately to his resignation as superintendent of schools in October.

Responsibility, he says, is what a resistant "organizational culture" shirks as it focuses on protecting itself rather than solving problems.

Responsibility, he says, was absent in political leaders as well as members of the public who wished him well when he took the prickly job in 1998, but did little else to help him along.

Responsibility, he says, is what he sought from the Board of Education in tendering his resignation, placing before the members the decision of his fate.

|

Yet in the definitive sense, it would appear that LeMahieu's fall rests principally with himself. The catalyst was his choosing to engage in a "personal relationship" with a woman with whom he had professional dealings. In itself, the matter was not ruinous. Citizens familiar with similar indiscretions by other public officials were not scandalized. But the wound bled into the ambiguity of conflict of interest. Moreover, it appeared to damage LeMahieu's image of himself as one who tried his best not to hurt others. Miscalculating his footing and the board's disposition, he offered up his job.In the months since his departure, LeMahieu has kept his head down. He emerges now with vigor to tell his side of the story, requesting meetings with the Star-Bulletin and other news organizations.

He has grown a beard and sports a diamond stud in his left ear lobe, dressing down from suit and tie to casual aloha shirt. Unlike in previous visits, he has no documents to distribute, no entourage of education department officials, just a lawyer friend who prompts him to make certain points.

He remains the skillful, articulate academic authority, maneuvering deftly through discussions about special education and the Felix consent decree. His intuitive nature is honed and readily deployed to nestle into the sensitivities of his questioners.

Going public, LeMahieu says, is "my last best effort to make things better here." He fears that the reports from the investigative committee and state auditor Marion Higa as well as the entrenched bureaucracy of state government will permit public education to slip further into mediocrity.

His altruism is difficult to separate from the perception that there is a desire to defend and reinvent himself. At times, LeMahieu presents himself as a victim, "collateral damage," he says, to a gang of peevish politicians trolling for dirt. At others, he acknowledges soberly his own culpability.

The contradiction is further manifest in his descriptions of state government and its employees, by turns, as an impervious bureaucracy or a willing partner in seeking improvement.

Presented with a comparison of the state's organizational culture to a 23-page military specification on how to make a Christmas cake, LeMahieu responds sardonically that "people here would love those 23 pages."

The attitude among bureaucrats is that "it doesn't matter if the cake ever gets made and it sure as hell doesn't matter what it tastes like when it gets done. As long as I'm in the right place on the 23 pages at any step along the way, my failures are perfectly acceptable."

The bureaucracy in Hawaii, he says, "has finely refined skills at problem avoidance as opposed to problem analysis and solution. I think it mistakes finding someone to blame for serious efforts at solving our problems, which is why all our problems are still here, although along the way we found a lot of people to blame."

In a later conversation, LeMahieu qualified that assessment, praising many state workers for embracing his initiatives. "I want it to be known that the folks in the schools, the DOE, people in public schools, wanted to change. This place has made more progress faster than any other place. There are lots of professionals who are hungry for change."

Unequivocal, however, is LeMahieu's harsh criticism of the legislative committee and Higa, whose office is incorrectly, from his view, "committed to the belief that problems should be solved by legislative action, that the Legislature is the body to control and direct things and thereby solve problems."

He challenges the intellectual honesty, methodology and analytic ability of the auditor's office, which he characterized as a "barking dog," saying "more barking dogs do not help organizations perform better."

While LeMahieu concedes that it is the duty and the right of the legislative panel to ask questions about how money for special education is being spent, he wonders whether its motives may run along a different course.

Much to their annoyance, lawmakers have had to cede their power to control the state budget on special education to a federal judge, David Ezra, he argues. "I think it is the root of considerable frustration among some political leaders who feel displaced from what they think is their rightful place."

He contends that the report the committee has produced contains little evidence -- other than vague testimony from education officials he considers disgruntled employees -- to claim any wrongdoing or mismanagement of money. "What I'm convinced of is that if there was anything bigger and anything juicier, you would see it in the report."

Confronted with the notion that the dearth of specific evidence may be due to the education department's inability to provide information about spending, LeMahieu takes a sharp turn.

"The DOE cannot tell you about expenditures in a timely fashion or at all well. That's absolutely true," he admits, but only to place the responsibility with the Legislature, who rejected his request for money to correct the problem.

As for the reason he offered to resign, LeMahieu continues the theme of responsibility. "I placed my resignation in the board's hands. In doing so, I expanded the net of responsibility. Anybody involved could have said, 'Wait a minute...it's not a good thing for you to go, it's not necessary.' It didn't happen. All of the people who said we're behind you, we support you -- no one took responsibility individually."

As to how much responsibility he holds in the problems of the DOE, he says, "I'm not to blame for this place's problems. I'm not at all responsible. I tried to be part of the solution."

Where his accountability is clear is in the matter of the personal relationship. "That hurt people. I have to take responsibility for that. The personal thing was my own doing. To be honest, the responsibility for your integrity is your own."

The public humiliation weighs on him and swayed him toward resignation. "It was tremendously powerful in influencing my decision," he says.

"The one thing I didn't want to do was to be a distraction from the important work the system was engaged in, being an embarrassment, being the sort of person who ..." He leaves the sentence unfinished.

Had he been offered a chance to return to the job, LeMahieu's response would have been "a resounding yes," but this avenue was closed when the board hired Pat Hamamoto, who had been his deputy for two years.

Her $150,000 salary, the maximum amount the Legislature set last year, stings against the $90,000 he was paid. "The position deserves it," he says in a voice traced with weariness.

"The biggest regret is to folks who I let down, to starting the work and not getting it done," he says.

That regret may be shared by many who had high hopes for LeMahieu. His departure should not be viewed entirely as the fault of one entity, be it the committee, the auditor, political leaders or LeMahieu himself. Rather, it came through the culmination of severe financial costs for a special education program left too long undone and a placid acceptance of low expectations.

As LeMahieu says, "There's plenty of responsibility to go around."