Sunday, November 11, 2001

Gleefully, third-graders from Maemae School in Nuuanu dip small nets into the shallow waters of a pond off West Loch, Pearl Harbor. With chirps of excitement, they catch toads, tadpoles, tilapia, crayfish and snails. After proudly showing off their inventory, they let the animals go.

Much of Hawaii's environmentally

Combining roles difficult

valuable land falls under the protection

of the military. Lately, that's good.

By Jim Borg

jborg@starbulletin.comEarlier, an endangered Hawaiian coot prowled the nearby pickleweed.

The wetlands at the edge of the busy naval base represent a happy accommodation between nature and human activity. Just outside the accidental blast buffer zone of the West Loch Naval Magazine - a storage site for cruise missiles and torpedoes - the ponds provide a habitat for four endangered native birds. And they illustrate a point perhaps not widely appreciated:

Despite unfavorable impressions left by the bombing of Kahoolawe and live-fire training in Makua Valley, the U.S. military has become an effective - if at times reluctant - protector of the environment. William J. Perry, who was secretary of defense in 1996, set a tone that continues today: "The Defense Department must have an environmental program that protects our troops and families; that manages our training and living areas carefully; that fulfills our obligation to be good citizens to the community in which we live; and that sets a good example to militaries around the world.""You have to give them credit for the resources they've dedicated," says Jeff Mikulina, director of the Hawaii chapter of the Sierra Club.

"They have a lot of good programs in place," says Ati Jeffers-Fabro, education director of the Hawaii Nature Center.

"We can always do better, but since environmental stewardship became part of its mission, the military has put more resources and dedicated people into managing its areas than the state or other landowners," says Gilbert Coloma-Agaran, director of the state Department of Land and Natural Resources.Among the military's "green" achievements:

>> At Mokapu Peninsula in Kaneohe, Marines since the early 1980s have maintained a refuge for red-footed booby seabirds at Ulupau Crater and a wetland habitat at Nuupia Ponds. They have used amphibious assault vehicles to clear out mats of invasive pickleweed, and volunteers and contractors have removed 20 acres of mangrove. The Hawaiian stilt population has increased from 60 to 130 birds."What a great job to be out there protecting natural resources and trying to preserve them for future generations," says Kapua Kawelo, a full-time Army civilian with a degree in botany from UC Davis.>> At Kaneohe and Camp Smith, the Marines are finishing a landscaping program to replace alien plants with native species like hala, ohai, naupaka and beach morning glory.

>> Hickam Air Force Base has an aggressive recycling program and a system to control CFC refrigerants, which destroy the ozone layer when released to the atmosphere. With an annual budget of $12 million, the Hickam Environmental Restoration Program is exploring novel methods to clean up areas contaminated with aircraft fuel. These include "phytoremediation" - the use of trees, and "bioslurping" - vacuuming up fuel floating on the underground water table.

>> At the 109,000-acre Pohakuloa Training Area on the Big Island, the Army protects about 20 rare, threatened or endangered species of plants and animals, including the Hawaiian hoary bat. Pohakuloa has the highest concentration of endangered species of any Army installation in the world.

>> At its Oahu training areas, including Makua, the Army employs a full-time staff of eight environmentalists to manage habitats for 57 species of endangered plants and 11 species of endangered animals. That includes controlling harmful alien species and reintroducing threatened native species to the wild.

Poison oysters

Like many industries over the last 100 years, the defense establishment has exacted a heavy environmental toll.Much of Kahoolawe, the military's former "Target Isle," remains riddled with unexploded ordnance from decades of naval shelling and bombardment. The Navy says 37 percent of the island has been cleared, including 8,700 surface acres and another 1,100 acres to a depth of four feet.

Soil and groundwater around Schofield Barracks for years were contaminated with the chemical trichloroethylene (TCE), but the EPA removed Schofield from its "Superfund" National Priorities List in August 2000. On the Big Island, the Army's $30 million Multipurpose Range Complex at Pohakuloa remains idle after a lawsuit alleging that its construction harmed the dryland habitat of endangered plants.

At Pearl Harbor, not all of the problems can be pinned on the Navy; witness the May 1996 Chevron fuel spill in Waiau Stream that flowed into East Loch. The estuary's oyster population fell victim to overharvesting and agricultural runoff long before the fleet arrived in force. Today, the shellfish are back, but the state forbids harvesting them because they're unsafe to eat.Still, a symphony of environmental insults launched the naval complex onto the Superfund list in 1992. Today, the full extent of Pearl Harbor's pollution from underground oil and industrial chemicals can only be guessed at.

Class action

In that context, it is remarkable to see programs like the one at West Loch.Formally known as the Honouliuli unit of the Pearl Harbor National Wildlife Refuge, the ponds lie on 36 acres leased by the Navy to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The agency maintains the habitat for native plants and birds, including the endangered stilt, coot, duck and moorhen. Off limits to the general public, the habitat is open weekdays each fall to third-grade classes in a program administered by the Hawaii Nature Center. Jeffers-Fabro says 3,000 third-graders annually take part in the half-day program at the refuge, a short walk from West Loch Fairways housing.

"The interest you see in the kids' faces is just phenomenal," says Donna Stovall, manager of the three national wildlife refuges on Oahu.

Last month, tagging along with a class from Maemae School, I was struck by how well the excursion balances two potentially conflicting goals: protecting fragile wetlands from human intrusion and conveying the environmental merits of a marsh.

Teacher Jan Zane-Chin said it's one of her most popular field trips: "I bring my class every year."

The students arrived nearly bursting with answers as Hawaii Nature Center guide Lara Lagos quizzed them on wetland ecology. On their refuge tour, the Maemae students learned more about the interrelationship between their captured critters, the mud and fresh-water shallows, the plant life and native and migratory waterfowl. They learned of the dangers posed by alien species like cats, rats and mongooses.

"Are we bad for our endangered birds?" Lagos asked the children.

"No-o," several answered, knowing that they would never purposely hurt a bird.

"Actually, we are," Lagos replied, explaining that a large or continuous human presence would throw the ecosystem out of sync. Only by special permit are they allowed in, she said. "I can't go in unless I'm with you guys. You can't go in unless you're with me."

An inexact science

The Pearl Harbor National Wildlife Refuge saw its genesis in a land swap resulting from the expansion of Honolulu Airport. The late Betty Nagamine Bliss of the Audubon Society led the effort to acquire property to replace the habitat lost with the construction of the reef runway.Largely through her efforts, the Pearl Harbor refuge, including a 24-acre site at Waiawa, was created in 1972. The Waiawa wetland is next to the Pearl City Peninsula Landfill, a former toxic waste dump that helped Pearl Harbor earn its Superfund designation. Stovall says the Fish and Wildlife Service is working with the Navy to assess the risk to wildlife there. In 1999, the Pearl Harbor refuge expanded to incorporate 37 acres of coastal drylands once part of Barbers Point Naval Air Station.

At Honouliuli, the growth of alien plants made the site less suitable to waterbirds. Federal caretakers tried to get rid of the interlopers by manipulating water levels, but it didn't work. So in August 2000, with the help of Seabees operating heavy equipment, the wetlands were redesigned to create a more favorable environment. Periodically, one of the two ponds is drained to eliminate the invasive species and to aerate the mud.

"Wetland management is not an exact science," says Stovall. "We are always trying to see what works and what doesn't."

Plans are afoot to build an elevated overlook at the edge of the refuge, which would give the general public a view of the ponds from the proposed Pearl Harbor Historic Trail.

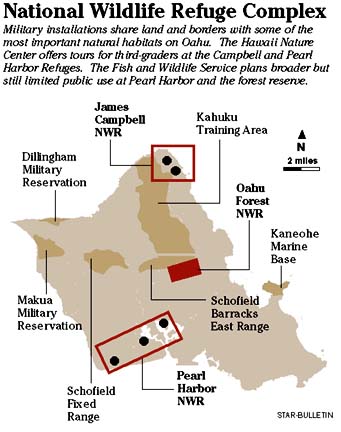

Meanwhile, the Honouliuli program for third-graders, begun in 1992, has grown so popular that it has a formidable waiting list. The Hawaii Nature center last year began a similar wetland tour at the James Campbell National Wildlife Refuge in Kahuku. The island's third federal nature preserve, the Oahu Forest National Wildlife Refuge, opened last December on 4,500 acres in the central Koolaus bordering the Schofield Barracks East Range.

Over the last 30 years, as Congress has tightened laws to protect the air, water, marine mammals and endangered species, the military has found itself in the role of environmental guardian on its vast tracts of undeveloped land. Many of these once-isolated areas have become de facto nature preserves in the face of encroaching urban sprawl. Combining roles of warrior

and caretaker can be difficultEven before the September terror attacks, the Pentagon showed signs of discomfort in its attempt to balance its primary mission - protecting the nation - with protecting nature.

"The challenge to achieve acceptable mission readiness stems in part from increasing environmental laws and regulations and commercial and urban encroachment," Vice Adm. James Amerault, deputy chief of naval operations for fleet readiness and logistics, told the House Armed Services Committee on May 22. "One of the most difficult challenges we face is to comply with the Endangered Species Act and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act without reducing our ability to 'train as we fight' on our ranges."

In August, a group called Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility released documents it said showed the military was preparing to ask Congress to exempt certain training exercises from environmental laws. A Defense Department spokesmen questioned the documents' authenticity.

Such a move by the Pentagon would seem less surprising in the aftermath of Sept. 11.