Sunday, October 28, 2001

The well-worn cliche, true nonetheless, "those who don't remember history are doomed to repeat it," might have gone through the mind of retired naval officer H. Tucker Gratz as he made his way onto the shattered hulk of the USS Arizona in 1946, there to place a lei in commemoration of the Japanese attack of December 7, 1941 -- and found the wilted remains of the lei he had placed the year before.

Battle to keep history alive can be grueling

By Burl Burlingame

bburlingame@starbulletin.comWithin a few years, Gratz was heading the Pacific War Memorial Commission, a private organization tasked with making sure the Pacific War, that part of World War II fought between America and Japan, would be remembered by future generations. The organization faced severe bureaucratic challenges, and achieved some notable successes, and then vanished, consumed by the abyss of state government.

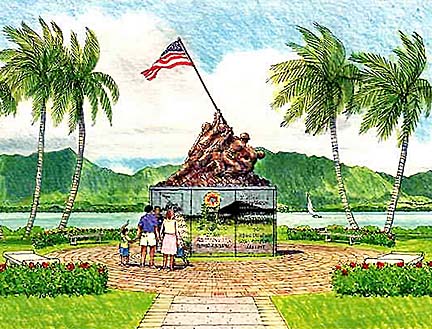

Today, the Pacific War Memorial Association, a similar organization, with similar goals and grass-roots support, is facing the same challenges. Created in 1998 by sparkplug Alice Clark and husband Bee Clark, a Big Island couple who have led the way for years in educational projects, to erect a memorial to the Marines who trained at Camp Tarawa on the Big Island during the war, the organization quickly noticed that there was no memorial that commemorated the sacrifices made by all services during the Pacific War.They chose as their icon the American flagraising on the Japanese volcanic isle of Iwo Jima -- one of the most-recognized images in modern times -- and sought to recreate the famous statue in Hawaii. A reproduction casting was arranged. Where to put it? The association entered into a long-range planning process with the Navy, currently in the midst of plans to reshape the historic landscape of Ford Island. After several years of vague run-arounds, the association got the message -- the Navy will not allow a memorial to other services on Navy property.

The association turned to the Marine Corps, asking about the cusp property fronting Marine Corps Base Hawaii in Kaneohe, and received a thumbs-up literally within days. The monument will be dedicated in March.

Like the commission of yesteryear, the association of today has a vision of coordinating Hawaii's war memorials -- the National Cemetery in the Punchbowl, the sunken battleship Arizona, the retired battleship Missouri, the submarine Bowfin, the Army Museum at Fort DeRussey in Waikiki, plus archives, museums, seminars, symposiums and courses of study. While each site would continue to be run by its present agency or private organization, they would be integrated into a whole for the education of coming generations and to draw tourists from the mainland and from Asia.The earlier commission, however, didn't get there; the vision was too grand and too far-reaching. Today, the association has its hands full at the moment dealing with a single project, but the opportunity is there for carrying on the vision. The question is whether its is doomed to repeat history.

Ideas to memorialize the disaster at Pearl Harbor sprang up almost immediately, including a 1943 plan to erect a giant statue of radar operator Joseph Lockhart, whose warnings of the incoming Imperial Navy aircraft were ignored. He would be staring sternly into the air, and presumably into the hearts of Americans. By the end of the war, the Pearl Harbor Memorial Trust, a coalition of civilians and veterans, was in existence, a reflection of an inchoate need to mark the conflict. No one could agree how.

After the war, an East Coast organization called Pacific War Memorial, Inc., sprang into existence, with a golden board of directors -- William Donovan, wartime head of the Office of Strategic Services; Oveta Culp Hobby, first commanding officer of the Women's Army Corps; Henry Stimson, former Secretary of War; and a flock of Rockefellers and Roosevelts -- to develop scientific fishing methods. The Hawaii-based commission was tapped by the territorial legislature to become the local liaison, but the fish-for-food science project fizzled before it got started.

The commission turned its attention to suitable Hawaii memorials. The hulk of the USS Arizona was a logical place to start, and by 1950, with commission influence, the Navy erected a flagstaff and wooden platform atop the sunken battleship for ceremonies. The Navy added plaques to the Arizona and the nearby USS Utah.

The 1950s was an era of intense debate about what to do next, exacerbated by bureaucratic turf wars. At the heart of it was a fundamental question -- what exactly would a memorial memorialize? There was public pressure to commemorate the Pearl Harbor attack, but the Navy, including the commission's honorary chairman Adm. Chester Nimitz, preferred not to dwell on a Navy defeat. The Navy opposed federal funding for such a memorial, and the idea foundered.

The commission also had to deal with the heavyweight American Battle Monuments Commission, the quasi-governmental agency charged with the care of military monuments. Enthusiastic civilians were erecting memorials right and left with nary a thought of long-range upkeep. The ABMC noted that an Arizona memorial would be an all-Navy show, and the other services left out.

At one point, both the Pacific War Memorial Commission and the semi-official Fleet Reserve Association were operating competing fund drives for an Arizona memorial, and the Navy had no authorization to collect funds from either organization. There was a welter of sore feelings and unaudited fundraising activities, while the participants tried to figure out how to erect a memorial on Navy property.

The logjam was finally broken by congressional approval to use federal funds for building the memorial, and Alfred Preis' striking monument over the Arizona was dedicated in 1962.

Immediately, the commission realized that the memorial was not enough. There needed to be shoreside facilities and a tourboat system for the public. By the late '60s, long lines of visitors broiled in the sun as the Navy ran a ferry operation out to the memorial. The Navy turned to the commission for help. The organization, still smarting over the confused fund-raising and planning efforts of the 1950s, went directly to Congress.

From the beginning, local Navy commanders demanded that any shoreside facilities be operated by the National Park Service, the governmental branch experienced in such affairs. Top Navy officials were horrified. "Under no circumstances should the operation and maintenance of this Navy Memorial and its supporting facilities ... be transferred to another U.S. agency," noted CINCPAC in 1967, underscoring the Navy's proprietary sense toward Pearl Harbor history.

Without enabling legislation, which defines a park's mission and scope, the Park Service wanted no part of the Navy's facility and testified against their involvement during congressional appropriation hearings. At the same time, the Navy was insisting that a visitor center that would become Navy property be built with Park Service funds. The commission mediated, and by the late '70s a compromise was reached. The Navy constructed a visitors' center with privately-raised funds, and then transferred operations and maintenance to the park service. It opened in 1980.

In 1981, the commission, exhausted, was disbanded and its duties anonymously absorbed by the Department of Land and Natural Resources.

As for the plans of its successor, the Pacific War Memorial Association, the question remains: Can it integrate Hawaii's war memorials, or will it disappear, exhausted by governmental infighting, once the goal of a joint-services monument has been reached?

A memorial is a continuing civic process and responsibility. Unlike old soldiers, the lessons of the past shouldn't just fade away.

What: The Pacific War Memorial Association is a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization Pacific War

Memorial Association

Address: P.O. Box 1761, Honolulu, HI 96806.

Information: (808) 533-3759

Online: http://www.pacificwarmemorial.org or by e-mail at: pacificwarmemorial@hawaii.rr.com.