Sunday, October 7, 2001

THE MISSILE DEFENSE SHIELD

Will it work? ON A RIDGE above Kaena Point, a white radar dish lifts and swings on its lubricated cradle, making a sound like a robot in a science-fiction movie. A rare panorama spreads out from this finger of the Waianae Mountains. One flank drops away to dry scrubland and empty beaches along the Leeward Coast. From the other, the North Shore fades off into the misty distance. At peace in this retreat, about 1,000 feet above sea level, a pair of nene geese scurries across the asphalt roadway.

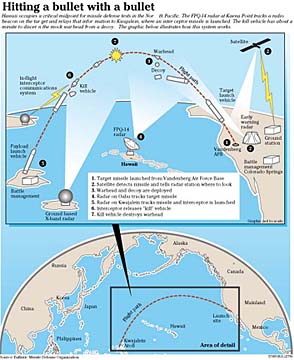

Hitting a warhead on the wing

requires luck and the highest

of technologies» Minding radar's P's and Q's

» Do we need it? Opinions.By Jim Borg

jborg@starbulletin.comThis pastoral landscape is the improbable setting for a vital element of the nation's ballistic missile defense program. Scaled back from the "Star Wars" initiative championed by President Reagan in the 1980s, the plan aims to protect the United States from a far less formidable threat: a missile launch by a "rogue" nation such as North Korea or the accidental launch of a missile from Russia or China.

For the Bush administration, missile defense remains an international security priority even in the wake of the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. "We saw a terrorist attack that used a different form of delivery within our borders," White House spokesman Ken Lisaius said on Wednesday. "That attack does not mean there are not other threats out there, and those threats need to be addressed as well."Moreover, the Pentagon's Quadrennial Defense Review to Congress last week reestablished homeland defense as the department's "primary mission."

Depending on who's talking, ballistic missile defense is:

>> A sensible, moral alternative to "mutual assured destruction" -- the basis for nuclear deterrence during the Cold War, or

>> A costly pipe dream.

Most discussions of the program focus on policy or budget priorities. Wouldn't the $8 billion annual budget be better spent on schools, an airline industry bailout, counterterrorism, upgrading defense hardware, raises for the military? Wouldn't breaking the 1972 ABM Treaty erode our relationship with the Russians? Wouldn't diplomacy work better?

Ideological arguments often ignore the immense technological challenges facing any missile defense system, sometimes compared to "hitting a bullet with a bullet." Of the four intercept tests so far, two have failed. The most recent test, which took place north of Hawaii on July 14, was considered a success. In fact, it was an amazing achievement. The military hopes to score another hit in early December. But no test so far has been completely realistic and none is likely to be so for many years to come.

Fire in the sky

This "hit-to-kill" testing program, focused on shooting down a missile mid-course, requires disparate elements thousands of miles apart to fall into coordinated place within a very short time.From Vandenberg Air Force Base, north of Los Angeles, a 63-foot-tall Minuteman II ICBM blasts off and arcs over the Pacific. It is 7:40 p.m. Pacific Daylight Time, or 4:40 p.m. Hawaii time, July 14.

In tests like this one, known as Integrated Flight Test 6, Vandenberg plays the role of a nation launching a missile at a U.S. city or military base. If fired in anger or by accident, the missile presumably would be tipped with a nuclear, biological or chemical warhead. The target is Kwajalein atoll in the Marshall Islands.

Within 35 seconds, a military satellite detects the launch by the infrared heat signature of the rocket plume. It alerts the battle management center operated by the project's top contractor, Boeing, in Colorado Springs, Colo. Within a minute, a radar at Beale Air Force Base, Calif., begins to provide positioning data to Boeing's 12-person battle management team. The information is relayed to Vandenberg and the Joint National Test Facility at Kwajalein.

A minute and four seconds after launch, the first-stage booster stops firing and separates, tumbling back toward the ocean. The second-stage booster blasts to life, and the shield that covers the tip of the rocket, called the nose fairing, falls away, uncovering the cone-shaped reentry vehicle -- the mock warhead. After another minute, the second stage separates and falls.The third and final stage erupts, accelerating the payload vehicle or "bus" to 14,700 mph. At an altitude of 60 miles, the missile leaves the atmosphere. It ascends another 15 miles before the booster burns out. Three minutes into the launch, the bus is climbing through space, following a trajectory governed by gravity and its own momentum.

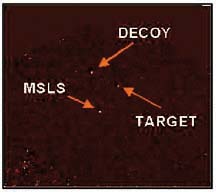

At seven and a half minutes into the flight, the bus inflates a helium balloon, released as a decoy. This sounds simple enough, but during the previous test, on July 7, 2000, the Mylar balloon failed to inflate. The bus also releases a mock warhead, 6 feet from base to tip. If left alone, the dummy warhead will dive back down through the atmosphere, splashing into Kwajalein's blue lagoon.

Beeps in the key of C

Above Kaena Point, the 29-foot dish whirs on its hydraulic housing, settling on a spot in the sky beyond Sunset Beach. Inside an adjacent, air-conditioned control center, civilians working for ITT Industries, the contractor, monitor display panels. They have been instructed not to talk publicly, but they know the stakes are high.Kaena Point's radar, operating at a C-band frequency, is not powerful enough to discern a warhead from a decoy. To make up for the radar's weaknesses, the mock warhead on this test has been fitted with a C-band transponder -- a radio beacon. As the warhead climbs over Hawaii's northeastern horizon, Kaena Point hears the beeps and, at 11 minutes and 38 seconds into the flight, sends information on the warhead's velocity and projected track to Kwajalein.

Six minutes later, the more powerful X-band radar at Kwajalein detects the "target cluster" -- warhead, decoy and bus -- at a range of 2,800 miles. Within about a minute and a half, it distinguishes the warhead from the other objects.

Just past 5:01 p.m., Hawaii time, a two-stage interceptor missile blasts off from Kwajalein. This is another small victory. In April 1998, during Integrated Flight Test 1, the interceptor was incorrectly programmed and failed to lift off.The interceptor missile carries a "exoatmospheric kill vehicle" designed to find the warhead and crash into it. It packs no explosives, so must achieve a direct hit. From the Kwajalein radar data, it has a good idea where the target cluster is but must pinpoint it with its own sensors. It cannot hear the warhead's C-band beeps.

After a flight of 51/2 minutes, the kill vehicle separates from the second-stage booster. (In July 2000, the kill vehicle failed to separate, dooming Integrated Flight Test 5.) Using onboard thrusters, the space- borne assassin points its telescope at two stars, Spica and Polaris, to confirm its position. It then maneuvers to receive a target position update from the Kwajalein radar.

Finding the target

The kill vehicle initially spots the target cluster at a distance of 450 miles. This is impressive because the kill vehicle's sensors have a 1-degree field of view -- comparable to looking through a soda straw. Closing at a relative speed of about 16,500 mph -- more than 4.5 miles per second, the kill vehicle has less than 100 seconds to pick its target and make last-minute course corrections.More than two dozen factors -- all secret -- are weighed by the kill vehicle's on-board computer to spot the cone-shaped reentry vehicle, says Lt. Col. Rick Lehner, a spokesman for the Ballistic Missile Defense Organization. The most important almost certainly include the brightness of reflected light, relative size and shape and infrared heat signatures.

The kill vehicle's target-hunting eye relies largely on optics -- it must "see" the objects in the dark of space. That, the system's critics argue, represents the program's most glaring vulnerability.

At 5:08 p.m., Hawaii time, as the sun drops in the western skies, the kill vehicle has that light source at its back as it examines the rapidly approaching target array.

MIT Professor Theodore Postol says the sun's position gives the array a predictable set of characteristics. In the last four tests, he says, the balloon decoy was "roughly 10 times brighter than the warhead in the infrared and therefore easily distinguished from the 'less bright' warhead."

He adds, "With prior knowledge that the dim object is the mock warhead, they have in no way demonstrated an ability to discriminate warheads and decoys."

Even under optimal conditions, serious complications loom.

>> Deadly chemicals and disease-carrying biological agents could be placed in so-called submunition "bomblets" too small and too numerous to be tracked.

>> Missiles could hatch a large number of decoys of varied sizes, shapes and reflectivity. Some could be filled partly with water that could mimic a warhead's infrared profile.

>> The warhead itself could be hidden inside a Mylar balloon. To all appearances, it would look like a decoy.

"It is easy to design the decoys and warheads to be indistinguishable from one another," says Postol. For testing purposes, he adds, "It is also easy to design them to be distinguishable."

Fury without sound

About 1,000 miles west of Hawaii at an altitude of 144 miles, the target array and kill vehicle close at a dizzying combined speed of 24,000 feet per second.Approximately 64 seconds before anticipated impact, a software glitch occurs that prevents the kill vehicle from getting updated information from ground radar. It goes ahead and commits to one of the specks in view. The decision is critical because the mock warhead and decoy are 3.5 miles from each other; the warhead and the bus are 1.1 miles apart. So it can't hit the wrong one and hope the resulting explosion will wipe out the warhead.

Even if it has made the correct choice, things can still go wrong. During Integrated Flight Test 4, on Jan. 18, 2000, the kill vehicle's infrared sensor overheated 6 seconds (27 miles) before anticipated impact and it missed.

The July 14 test proceeds without further hitches. Seconds before destruction, the kill vehicle transmits its final target image -- a bright blur in the shape of a guitar pick. An instant later: a furious collision and blinding light in the airless silence of space. It is 5:09 p.m.

The verdict?

"It's an impressive demonstration of a very high degree of precision guidance and control," says Postol. "But I don't think it has anything to do with a militarily capable missile defense."

Hitting the 'sweet spot'

Air Force Lt. Gen. Ronald Kadish, director of the Ballistic Missile Defense Organization, says the four most recent tests focused on hitting the warhead's "sweet spot," not on target discrimination.In two earlier flybys with nine decoys, the kill vehicle's sensors performed up to expectations, he says. Kadish insists the regime gradually will become more realistic, with additional decoys and other countermeasures intended to fool the kill vehicle.

Yet the Vandenberg-Kwajalein test range can't replicate all the scenarios that might be encountered in the real world, Kadish concedes.

"Added to this are range safety concerns -- that is, the safety of ocean vessels and the populations of Hawaii and the Marshall Islands, which restrict us to a limited number of trajectories and intercept altitudes and velocities that are on the low end of how we would like to test," he told Congress in June.

More money's on the way to increase the realism. In late summer, the Bush administration proposed $800 million in upgrades to the Pacific testing range, including a new high-resolution radar for Hawaii.

AN/FPQ-14 is the obscure, formal designation for the Kaena Point radar, a Hawaii fixture since the dawn of the space age. The letter F stands for fixed -- meaning it's not moving on a ship or plane -- but that's the only initial that will make sense to civilians. AN stands for Army Navy; the site belongs to the Air Force. Minding radar’s

P’s and Q’sP stands for radar. Q means special purpose. The 14 refers to the model number.

The radar is a C-band radar, sending out a narrow, medium-strength beam in the range of 5.4 to 5.9 gigahertz. That allows it to track objects in low earth orbit as small as 10 inches in diameter. One mission is to track orbiting debris that may pose a threat to space shuttle flights or the international space station. It spends 128 hours a week on its space surveillance mission.

The Kaena Point Satellite Tracking Station is part of the 30th Space Wing, with headquarters at Vandenberg Air Force Base, Calif.

Opinions from the missile defense system's defenders and detractors: Do we need it?

Sen. Daniel Inouye, (D-Hawaii), co-sponsor of the National Missile De-fense Act of 1999: "Anyone who studies North Korea, anyone who looks at the Soviet Union, anyone who has taken time to study the situation in Iraq and Iran, would have to conclude that there is a threat."

Sen. Joseph Biden (D-Del.), Chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee: "The real threats come into this country in the hold of a ship, or the belly of a plane or are smuggled into a city in the middle of the night in a vial in a backpack."

Baker Spring, Heritage Foundation research fellow: "The argument that the Sept. 11 terrorist attack disproves the immediacy of the missile threat to America is not just wrong; it is misleading."

Air Force Lt. Gen. Ronald Kadish, head of the Ballistic Missile Defense Organization: "The technical and operation-al challenges of intercepting ballistic missiles are unprecedented. While these challenges are significant ... they are not insurmountable."

Rep. Ike Skelton, (D-Mo.), a missile defense advocate: "It's hard to support a program that says, 'Let's buy everything and throw it against the wall and see what sticks.'"

Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz: "If, heaven forbid, something went wrong -- and I can't imagine it going wrong -- but if we had an accident with one of our missiles and it was shooting, flying toward Russia, I would dearly hope that they could shoot it down."

Retired Lockheed chief scientist Michael Munn: "Discrimination (of targets versus decoys) looks easy when you do it on paper. But you get up there and you never see what you expect."

Physicists Arno Penzias, Hans Bethe, Sheldon Glashow, Leon Lederman and 46 other American Nobel laureates, in a letter to President Clinton: "Anti-ballistic missile systems, particularly those attempting to intercept reentry vehicles in space, will inevitably lose in an arms race of improvements to offensive missiles."