Sunday, July 15, 2001

By Jim Borg

jborg@starbulletin.com

SCIENTISTS WANT TO STUDY HIM. American Indians want to bury him.Is he Polynesian, as the shape of his skull suggests? Or perhaps he's the descendant of Asian mariners who settled along America's now-sunken coasts.

A federal magistrate in Portland will soon decide the fate of Kennewick Man, a 9,500-year-old skeleton that may hold invaluable new clues to a perplexing old puzzle: Who were the first Americans?

"Kennewick is certainly stirring up a lot of feelings," says Rebecca Cann, a University of Hawaii geneticist.

College students stumbled across Kennewick Man five years ago this month on the banks of the Columbia River in Washington state. As nearly complete skeletons go, his is among the oldest found in the Western Hemisphere.

The bones are part of the growing body of evidence that is forcing scientists to recast their theories about how the New World was settled.

But their research has run headlong into a federal law called the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. The 1990 law requires ancient remains to be turned over to Indian tribes for reburial if a historic linkage or "cultural affinity" can be shown.

The Interior Department last fall decided in favor of the tribes -- the Umatilla, Yakima, Nez Perce and others.

Eight scientists challenged the decision in court, claiming Kennewick Man bears no resemblance to the Mongoloid ancestors of North American tribes. In fact, some scientists say Kennewick man looks more like an East Asian or Polynesian.

Those claims -- and other recent discoveries -- have sparked a highly charged debate.

Mainstream thought holds no Polynesians reached the Americas during the last Ice Age.

But mainstream thought has been turned on its ear in recent years.

Through most of the 20th century -- until 1997 -- leading scientists believed that the first Americans crossed from Siberia into Alaska about 11,500 years ago.

Back then, as the Ice Age was just ending, so much water was frozen in glaciers that the ocean was dozens of feet lower, exposing a land bridge across the Bering Strait.

Across this land bridge trekked the Clovis people, named after their characteristic stone spear point, first found in Clovis, N.M. They were believed to be hunters who followed mastodons, giant sloths and other big game across the Americas.

For decades, anyone who came up with a different scenario was ridiculed. Scientists who found conflicting evidence often covered it up for fear of endangering their careers.

Theories on Pacific migration

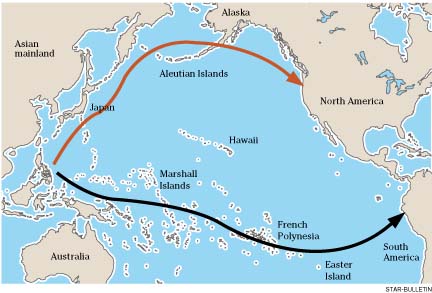

A coastal route around the North Pacific could have led early explorers to lands later submerged when melting glaciers raised sea levels. The possibility of an Ice Age migration directly across the Pacific is widely discounted, but Polynesians certainly had that capability by 500 A.D., when Hawaii and Easter Island were inhabited.

At dig sites, anthropologists would excavate down to the Clovis level -- to the dirt that was 11,500 years old -- and stop, so fervently did they believe that no earlier populations existed.Then a funny thing happened. Scientists excavated a camp site that was 12,500 years old.

Not only was it old, it was in southern Chile. That's a long walk from the Bering Strait.

How did these campers reach the southern latitudes of the Americas so long ago?

Maybe by boat.

"Early people might have moved south from the Bering Strait by following a chain of small ice-free areas that existed along the outer Pacific coast," Knut Fladmark, a professor of archaeology at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, told me by e-mail. "Many of those areas would now be underwater."

In 1997, Daryl Fedje, an archaeologist with the Canadian parks system, found a stone tool at a site now 160 feet under water off the coast of British Columbia. The artifact, 10,200 years old, shows that people once lived on that submerged land, Fedje says.

It will take more such discoveries to advance the theory of Ice Age ocean migration. But with affirmation of the discoveries at Monte Verde, Chile -- no bones, but plenty of artifacts, the old Clovis founding dates have died.

More fuel for the fire:

>> Johanna Nichols of UC Berkeley has argued that the wide diversity of languages among native Americans could have been achieved only after humans had been in the New World for 30,000 years.

>> Using DNA studies, geneticists Theodore Schurr of San Antonio and Douglas Wallace of Emory University in Atlanta argue that genetic diversity requires a New World presence of at least 30,000 years.

>> DNA studies of native American Indians have turned up five groupings of maternal ancestors. One of the five is found only in southwestern and central Asia -- and Europe.

>> The 10,800-year-old skeleton of a woman found near Buhl, Idaho, resembles today's Polynesians, according to Richard Jantz of the University of Tennessee. Chemical studies of the bones show she ate fish as well as meat. DNA testing was not allowed before she was repatriated, under federal law, to the Shoshone tribe.

>> Nevada's Spirit Cave Man, 9,400 years old, resembles the aboriginal Ainu of Japan or other east Asians more than American Indians, according to Jantz and Douglas Owsley of the Smithsonian Institution.

>> Two campsites in Peru -- Jaguay Canyon and Tacahuay Canyon -- estimated to be more than 12,000 years old, shows signs of maritime sustenance, including fishing nets and piles of fish bones and mollusk shells.

>> In Brazil, the oldest skeleton found in the Americas, a 11,500-year-old girl known as Luzia, has facial characteristics similar to those of people in southeast Asia, Australia and Melanesia, according to Walter Neves, a professor of anthropology at the University of Sao Paolo. Neves appeared on a fascinating and controversial BBC2 documentary in 1999 called "Ancient Voices: The Hunt for the First Americans."

Neves also points to cave paintings at Serra da Capivara in Brazil that show hunters chasing giant armadillos, Ice Age creatures long extinct. Other paintings show aboriginal settlers battling what could be invading Mongoloids, he says.

Neves suggests the Mongoloids eventually wiped out the aborigines except for a small group of mixed-blood natives at Tierra del Fuego, at the southern tip of the continent.

Since Hawaii and Easter Island, the far points of the Polynesian Triangle, were not occupied until about 400 or 500 A.D., it seems oddly anachronistic that mariners would have sailed across the Pacific to the Americas some 10,000 years before.

Perhaps as Australia was being settled 30,000 years ago, a contemporaneous wave of exploration took some groups north around the Pacific Rim and into the Americas. This would have required only a coastal maritime culture, not the trans-oceanic navigation perfected by the Polynesians much later.

One of the plaintiffs in the Kennewick Man case, University of Wyoming professor George W. Gill, cautions against the notion of direct settlement by Polynesians.

"Most of us who are working with Kennewick, Spirit Cave and others -- and who do clearly see links with Ainu, Polynesians and even Europeans -- do not believe that any of these groups necessarily contributed directly to the peopling of the New World," he says by e-mail. "Clearly some relative of these 'basic Caucasoids' did, but we are not at all prepared at this time to say who these migrants were. The Ainu, Polynesians and Europeans are all derived from some ancient Eurasian stock -- not clearly identified to everyone's satisfaction -- and therefore share a number of skeletal and soft tissue traits in common."

Mike Pietrusewsky of the UH anthropology department is even more adamant. "The claims that the Kennewick skull shows Polynesian (or even Ainu) affinities are on the weakest of evidence," he says. "The overwhelming evidence from physical anthropology, including molecular genetics, supports a Northeast Asian origin for the indigenous inhabitants of North/South America and definitely not one from Polynesia."

There is stronger evidence that Polynesians reached the Americas in pre-Columbian times, during or after the settlement of Oceania. (See related story.)

But until more skeletons like Kennewick Man turn up -- and unless scientists are allowed to study them -- the true identities of the first Americans will remain a mystery.