[ MAUKA MAKAI ]

WHEN THE ANCIENT Polynesians colonized the Hawaiian Islands, this most isolated archipelago became the epicenter of big-wave surfing. For centuries, the Hawaiian ali'i and maka'ainana, kane and wahine challenged the most fearsome waves the ocean would send their way. ‘Maverick’s’

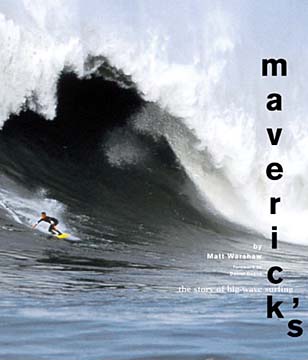

"Maverick's: The Story of Big-Wave Surfing''

recounts how Mark Foo

met his fate

By Matt Warshaw (Chronicle Books, 210 pages, color photographs, $30)

By Greg Ambrose

Special to the Star-BulletinDuring the 20th century, as surfing spread to the far corners of the planet, wave riders continued to converge on Hawaii to test their skills in the ocean's biggest waves.

In 1987, the surfing world was astounded to learn of a new big-wave mecca, off Todos Santos Island near Ensenada in Mexico's Baja. Still reeling from that discovery, in 1992 surfers couldn't have been more amazed if their surfboards had begun talking to them when they learned that a California surfer from Half Moon Bay had been riding cold, fog-shrouded monster waves at a menacing surf spot called Maverick's nearly within sight of San Francisco.

Suddenly, the big-wave surfing world was tilted on its axis. Hawaii was no longer the center of the surfing universe, but merely one of the bright stars that shone as a beacon to big-wave specialists.Maverick's might have remained a phenomenon known only to the surfing world but for a fateful encounter with Mark Foo, one of Hawaii's most flamboyant big-wave surfers.

A literate, insightful, informative book about surfing is a minor miracle. With his latest book, "Maverick's: The Story of Big-Wave Surfing," San Francisco writer Matt Warshaw has created a thing of beauty to be treasured by surfers everywhere. The book is also a passport allowing nonsurfers into the world of big-wave riding, that special, twisted branch of the surfing subculture.

Warshaw is uniquely suited to take readers on a wild ride in the ocean, as he is surfing's pre-eminent historian, having chronicled the sport's epic moments as editor of Surfer magazine, lifelong surfing zealot and owner of an unmatched multi-media surfing reference library.

In "Maverick's," Warshaw creates an odd kind of mystery in which a well-known victim, perpetrator, and the time and place of death are revealed in advance, but his deft writing and pacing keeps readers breathlessly turning pages.

Warshaw charts the separate development of one of surfing's most menacing surf spots and one of the sport's most chronicled characters as, an ocean apart, they move inexorably on a fatal collision course toward Dec. 23, 1994.

Foo's death at Maverick's achieved for him the worldwide recognition he desperately sought with endeavors such as his fatal mission to attain the trifecta of surfing a giant swell in Hawaii, and chasing those waves across the Pacific to Northern California and then down to Todos Santos in Baja.

As Warshaw lets the human drama unfold, he takes side trips, delivering entertaining examples of surfing's lore, legends and eccentric characters, as well as erudite discourses on meteorology, oceanography, undersea topography, hydrodynamics, physics and surfboard design and mechanics, explaining clearly how huge waves are created and ridden.

More difficult to reveal is the intense desire that causes surfers to leave the safety of shore to confront one of the most awesome forces of nature. Rather than ascribe motives, Warshaw provide clues, quotes and insights to enable readers to perform their own psychoanalysis of the seeming psychosis that drives surfers to challenge huge waves.

"Maverick's" also takes readers on a ride to the technology-boosted future of surfing. Human physical limitations and wave hydrodynamics have created a barrier to paddling into waves larger than 25 feet, what Foo often referred to as the unridden realm. But Waverunners and other personal watercraft have enabled surfers to enter the unridden realm of truly monstrous waves, a development that has thrilled partisans and outraged the sport's purists while opening up unexploited waves on distant reefs.

For nearly half a century after Dickie Cross died in huge surf at Waimea Bay in 1943, big-wave surfing was free from fatalities. But during a horrific four years in the mid-'90s, four surfers died while challenging big surf. Judging from the current resurgence of the popularity of big-wave riding, the very real prospect of a watery death might just enhance the thrill.

Still, a more common and inescapable problem exists for those who court the ocean's behemoths. Huge, perfect waves are extremely rare. And what do a thrill junkies do for their next fix once they have hitched a ride on a once-in-a-century monster wave?

Click for online

calendars and events.