EVEN FOR A FUNERAL, the mood was somber.

Kamehameha Schools Bishop Estate

ran a potent lobbying and political

action network, according to files

of the late Namlyn Snow

>> TROVE REVEALS ESTATE

>> ALL THE PRINCESS'S MENBy Rick Daysog

Star-BulletinBefore dozens of mourners at the Star of the Sea Parish, Henry Peters delivered a moving eulogy -- less than three weeks after his historic removal from his $1 million-a-year job as a Kamehameha Schools trustee.

Ex-House Judiciary Committee Chairman Terrance Tom -- whose cozy ties to the estate led to his election defeat seven months before -- accompanied the proceeding on the piano.

Former state Sen. Milton Holt, who would serve a one-year federal prison term for a mail fraud charge stemming from his failed 1996 re-election campaign, also was in the crowd.

The tragic symbolism of the May 1999 funeral for Namlyn Snow could not have been clearer. As Peters spoke, several in the audience felt they were witnessing the passing of a political leviathan whose influence extended throughout state government. Snow, who died of cancer, had headed the Kamehameha Schools Government Relations Division.

In many ways, she was the central nervous system for an organization that was more like Tammany Hall than a charity that educates native Hawaiian children.

The Star-Bulletin previously reported that the estate's former trustees secretly funneled tens of thousands of dollars in campaign contributions to dozens of isle lawmakers, lobbied Congress and the White House to preserve their hefty paychecks, conducted polls in the districts of legislators friendly to the trust's interests and played a role in the controversial 1999 confirmation defeat of Attorney General Margery Bronster.

But the complete story of the $6 billion trust's political clout and Snow's role in that shadowy network of power remained buried in the secret files Snow kept in her office.

During the past several months, the Star-Bulletin has reviewed more than 40,000 pages of records subpoenaed by the Attorney General's Office in its three-year criminal investigation into the political and lobbying activities of the Kamehameha Schools, formerly known as the Bishop Estate.

The raw investigative data -- which include Snow's records as well as 3,200 pages of sworn testimony from more than 70 witnesses -- show that the estate and its Government Relations Division played a bigger role in legislative process than previously thought and carried the type of clout enjoyed by Hawaii's big unions and the state's two largest banks.

A treasure trove of political intelligence show the trust's lobbying efforts, political influence and campaign contributions. TODAY

Key political players involved with the estate.

Admissions: How the former trustees and school officials played politics with Kamehameha Schools admissions. TOMORROW

The new estate: Under a new chief executive, the trust has implemented major reforms. However, the political legacy of the former trustees continues to haunt the trust. WEDNESDAY

The records show that trust officials:

>> Held private talks with state legislators to support land use bills that affect the trust even though the trust and its staffers were not registered as lobbyists.

>> Secretly drafted the language for bills, wrote and coordinated committee reports, rounded up witnesses to testify in favor of bills and wrote floor speeches for key politicians.

>> Kept an extensive database on politicians that included legislators' real property ownership records and their voting records on key bills.

>> Investigated lessees who criticized the estate's lease-to-fee conversion prices.

>> Held a private summit in 1991 with then-Gov. John Waihee, who offered to water down the administration's leasehold conversion bill in exchange for their support of his measure.

>> Created front organizations to conduct grass-roots lobbying on legislation without registering the activities with state regulators.

The political activities were terminated by the trust's chief executive officer, Hamilton McCubbin, and the estate's interim board, which took over the trust from ousted trustees Henry Peters, Richard "Dickie" Wong, Lokelani Lindsey, Gerard Jervis and Oswald Stender in May 1999.

However, the legacy of the estate's political machine endures in the legislation and in the land-use decisions that were passed, defeated or altered as a result of the trust's secret influence.

What's more, the trust's activities provide a rare glimpse into how business is conducted in Hawaii's political back rooms.

STATE LAW DEFINES lobbying as "communicating directly or through an agent" with a government official to influence legislation, administrative actions or a ballot issue. Lobbyists must register with the Ethics Commission if they spend more than five hours lobbying in a month or spend more than $750 on lobbying in a year.Until this year, the Kamehameha Schools has never registered any of its lobbying activities with the state Ethics Commission. The estate's former board said they did not lobby but had provided information at lawmakers' request or were monitoring legislation that potentially affected their interests.

Former trustee Peters added that the estate's political clout has been highly exaggerated.

"Think about it. If the estate was all powerful, why was it subjected to leasehold conversion where billions of dollars were stolen? How come its properties were constantly being taken by the state of Hawaii?" asked Peters, a former state House Speaker. "If we truly had so much power, how come we were removed from our office as trustees? So much for power and influence."

However, Snow's records indicate that she and other trust officials were not only actively attempting to influence legislation but were highly effective in passing, stalling or defeating legislation. Most of those behind-the-scenes efforts involved the estate's vast land holdings.

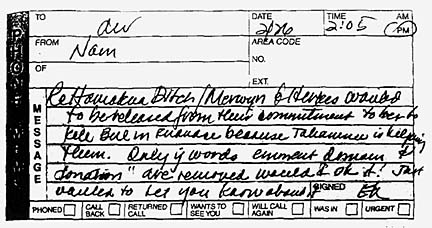

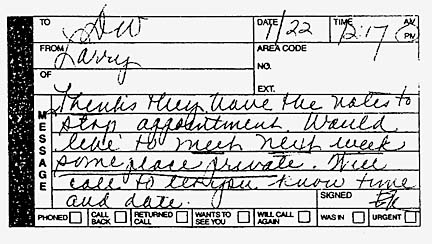

In a Feb. 26, 1996, telephone message, Snow told Wong's secretary that she spoke with then-state Reps. Merwyn Jones and Robert Herkes about a measure in the House Economic Development Committee concerning the Hamakua Ditch on the Big Island.

THE ESTATE ACQUIRED a majority stake in the ditch in 1994 when it bought 30,500 acres of former Hamakua Sugar Co. land for $21 million. The 24-mile irrigation channel provides water for many of the farmers in the area, but the ditch fell into disrepair when Hamakua Sugar went bankrupt.

Kamehameha Schools was attempting to work out a lease arrangement that would allow the state to take over the ditch's operations and repairs but bar it from taking the property through condemnation.

Herkes, then a trust employee and chairman of the Economic Development Committee, and Jones asked to be "released from their commitments" to Snow on the Hamakua Ditch measure, Snow's message said. Snow also said that the two legislators would support the bill only if the words "eminent domain" and "donation" were deleted from the language.

An attorney for Wong declined comment. Herkes said he was never lobbied by trust officials during his years as a state legislator. He said he did not think the Hamakua Ditch bill was referred to his committee.

Snow's records also showed that the trust attempted to orchestrate the passage of a leasehold conversion measure in the trust's favor.

IN A 55-PAGE REPORT prepared for an estate retreat at the Turtle Bay Hilton Hotel, Snow indicated that former Sen. Holt secretly introduced a bill during the 1994 session through former Senate President Norman Mizuguchi that gives big landowners the right to buy back any lands taken by eminent domain.

Snow's report, entitled "Lobbying Alternatives and Policies," said that Holt's role in drafting the bill was not disclosed since Mizuguchi introduced the bill.

At one point, a key Senate committee held the bill and the committee's chairman said he would hear the measure only if he received a request to do so from the general public, Snow's document said.Snow said the committee granted the bill a hearing after one of her staffers provided testimony under the guise of a family holding company. The committee passed the bill but it did not become law.

Mizuguchi, who stepped down from the Senate last year, was not available for comment and Holt could not be reached.

"(The) fact that it was a 'KSBE' bill was not widely known and therefore, it did not attract unnecessary 'knee-jerk' opposition," Snow's report said.

SNOW'S FILES also indicate that the estate relied on several front groups to lobby on its behalf.

The Kokua Network, whose members included many of the former trustees' friends and supporters, provided testimony in the Legislature, attended court hearings, wrote to legislators, sent letters to the editors of Honolulu's two daily newspapers and took part in sign waving for local political candidates at the request of the estate, according to Snow.

During the early 1990s the estate also helped create an organization to lobby against controversial mandatory lease-to-fee conversation measures, Snow's records indicate.

The group, known as Hui Pono Aina, said it represented a large cross-section of lessors in Hawaii, including small landowners. However, the group was partly financed by the estate's Government Relations Division, and its board included former trustee Oswald Stender and an attorney whose firm represented the trust.

According to Snow's report, the group produced and aired print, radio and television ads criticizing the city's mandatory leasehold bill, scheduled numerous news conferences attacking the bill and held editorial board meetings with Honolulu's two daily newspapers advocating their view.

While the City Council passed the bill due to the large public outcry over soaring leasehold rents, Snow's report said that the estate was able to blunt the damage due in large part to Hui Pono's efforts. Surveys conducted when Hui Pono was most active showed that public attitudes became more supportive of private-property rights, Snow's report said.

THE FORMER TRUSTEES took part in some behind-the-scenes lobbying of their own. An internal memo by trust attorney Stanford Manuia described a private meeting held on Feb. 25, 1991, between the estate's board members and then-Gov. Waihee on the leasehold controversy.

Manuia's memo, dated March 1, 1991, said Waihee requested the meeting to "salvage" his administration's leasehold conversion bill, which proposed a cap on residential leasehold rents. Waihee offered to exclude the Kamehameha Schools from the administration bill in exchange for their support, Manuia wrote.

The trustees, however, raised concerns about the rent cap and the formula that the state would use to determine the value of the leasehold land, Manuia said. The bill did not pass.

Waihee recalled meeting with the former trustees but said he did not offer to exempt the Kamehameha Schools from the administration bill. He said he was trying to strike a compromise on the leasehold controversy to help local homeowners whose lease rents had skyrocketed as a result of the early 1990s speculative land bubble.

Waihee -- whose firm, Verner Liipfert Bernhard McPherson and Hand, later billed the estate about $1 million to lobby Congress and the White House to protect the former trustees' salaries -- recalled that he accompanied former trustee Stender to Washington, D.C., in 1991 to meet with the Internal Revenue Service to resolve tax issues that may arise as a result of the bill.

"There was a lot of give and take going on to try to pass a bill," Waihee said.

HOLT, MEANWHILE, played a role in the estate's government relations efforts, confirming longtime suspicions that the former senator's employment at the trust conflicted with his duties as a state lawmaker.

Trust personnel records indicated that the estate expected Holt to use his position in the Legislature to provide the trust with political intelligence. One of the duties listed in a position description for Holt stated that he "conducts community reconnaissance to facilitate KSBE strategic planning."

In sworn testimony, Holt's former boss Gil Tam likened the ex-senator's role to that of a military intelligence officer for the trust. Tam said that Holt provided the estate with "G-2 intelligence," which refers to the type of information that a spy acquires at the battle lines.

"It's like ... what's happening at the Legislature, who's doing what, what strategies (are there) to consider," said Tam, a West Point graduate.

Bishop Estate Archive

Kamehameha Schools