Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

By Helen Altonn

Star-Bulletin

CONSUMERS eventually may find more red snapper available in restaurants and markets because of technology being developed at the Oceanic Institute to produce the fish.Scientists at the Windward Oahu facility are trying to cultivate red snapper in captivity for restocking of declining populations in the Gulf of Mexico.

In several significant breakthroughs, they achieved the first recorded spawns of red snapper in captivity and the first spawning outside the red snapper's natural reproductive season.

The Oceanic Institute is leading development of the culture technology in a consortium of research organizations. Partners include the University of Southern Mississippi's Institute of Marine Sciences and the Mote Marine Laboratory in Florida.

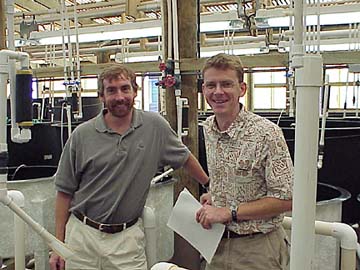

Oceanic Institute reproductive specialist Charles Laidley is working on spawning issues, and larval physiologist Robin Shields is wrestling with challenges of raising the larvae.

They said methods developed to raise red snapper also could be applied to opakapaka and other Hawaiian snappers and ornamental fish species.

Laidley said the red snapper project "has become a very large national issue, directly funded through Congress, because this species is the No. 1 commercial and probably the No. 1 sports fish in all of the Gulf of Mexico."

Thomas Farewell, Oceanic president and chief executive officer, said the institute's success with moi, mullet, Pacific threadfin and mahimahi "makes it uniquely qualified to make the breakthroughs necessary to culture snappers, ornamentals and other important species."He said the red snapper program is a high priority for the Oceanic Institute in a mission to address seafood shortages and environmental preservation.

Brian White, OI spokesman, said red snapper juveniles and fingerlings from the Mississippi area were flown here and put in "double quarantine" in laboratory tanks, since they are not native to Hawaii.

The spawning occurred over six days in late November, producing eggs that were up to 78 percent fertile, he said. Many intermittent spawns since then produced more than 100,000 fertile eggs each, White said.

The largest spawn produced about 150,000 eggs, Laidley said.

But the scientists are striving for a reliable method of producing the fish.

"Just doing it once is a big deal," Laidley said, "but a lot more needs to be done so we can rely on it."

He said red snapper generally grow and adapt well in captivity, but there are two bottlenecks to cultivating them: "getting them to reproduce in captivity ... and getting large numbers of larvae to survive under captive methods."

Being able to get hatched larvae makes the research easier, Shields said. "Now, we're dealing with locally generated material rather than ... shipping larvae all the way from Mississippi to Hawaii to work with."

"We have to get the animals, adapt them to captivity, try to learn about their natural reproductive cycles, their cycle in captivity, how they handle stress, and how to mitigate all those things," said Laidley, explaining that it is a slow process.

Shields said the team has managed to take the larvae through metamorphosis, from raising eggs to larvae to a small juvenile snapper. But the larvae are only about 1.7 millimeters long when they hatch, and finding the right feed for them is a problem.

The usual marine culture food organisms -- brine shrimp and microscopic invertebrate animals known as rotifers -- are too large for tiny red snapper larvae, he said.

The scientists are looking for alternative prey organisms that they can culture to improve the production process.

A broad research effort is under way to catch plankton in local waters and isolate certain species for cultivation.

"Rearing those types of plankton is more difficult than off-the-shelf organisms, rotifers, which we can produce in large quantities in the hatchery," Shields said.

That increases the costs, he said. "But we know it's worth pursuing. What we will achieve is control over the production process for this species."

Methods developed for the red snapper larvae diet also can be applied to Hawaiian snappers and ornamental species such as angelfish and yellow tang, the most abundant exported fish in the state, Shields said.

"There is a direct benefit to the state," he said.

Laidley said the institute's partners will develop stocking technology -- putting the fish in natural waters. But OI first has to solve the puzzle of how to culture the species.

The consortium not only is concerned with technology to raise red snapper, but is doing it in a responsible, ecologically minded manner, Laidley pointed out.

They are looking at effects on the Gulf of Mexico of stocking the fish, whether natural populations are displaced, the potential role of disease organisms, genetic diversity and other factors.

"It is a very integrated, collaborative approach -- a very exciting program," Laidley said. "We hope it will be a model for the world on how to do it."