Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

Permanent Link DURING a trip to Tahiti nearly a decade ago, Makaha surfer Rusty Keaulana was awakened at a friend's house by a strange sound. His curiosity piqued, Keaulana followed the mechanical staccato pulse to a room where his Tahitian friends were having their skin decorated by a stranger.

Tattoo you: Surfing's

marked men and womenBy Greg Ambrose

Special to the Star-BulletinThe tattoo man was paying a visit, creating indelible Polynesian designs on a canvas of skin, and Keaulana just had to have one. The result was a honu (sea turtle), the first of several artistic expressions of Keaulana's pride in his family and Polynesian heritage.

In one of the most colorful and unexpected results of the resurgence in Polynesian pride, youngsters throughout the Pacific are embracing the body art that astounded the first Westerners who explored the islands of Polynesia.

A whole generation of wave riders has become fascinated with the ancient Polynesian art of tatau. They embrace the painful piercing of flesh; the dull throb and sting of the needle; the bloodletting; the injection of ink under the skin to create wild designs that always provoke a response from those who view them; the fierce thrill of being marked as different, special, part of a clan.The reasons for spending a large amount of cash and enduring searing pain are as numerous as the people who seek such adornments, but the results are the same: a unique badge that lasts long after life has fled the body.

The tattoo man also came to the house where Laie surfer Duane DeSoto was staying in Tahiti, and because he had gotten excellent waves and made such good friends, he wanted a permanent reminder of his first trip to Tahiti at age 17. DeSoto also chose a honu as his design, although he was fascinated by one friend whose body was covered with tiger sharks and other traditional Tahitian designs.

Such markings were rare among past generations of surfers. When Anona Napoleon surfed in Waikiki during the '40s and '50s, she saw few tattoos on her fellow wave riders, just an occasional faded remnant of Navy duty and one beachboy with "Mother" inked on his shoulder. These days, when she hits the waves, Napoleon sees more and more surfers, even wahine, with elaborate designs across their backs and winding up and down their arms and legs. It's a huge investment in money and pain, but increasingly, surfers are willing to make such investments to make a statement.Of course, it pales in comparison to what the Polynesians endured before Western contact.

The hypnotic tapping of the wooden mallet on the serrated bone comb that pierced the flesh and left kukui nut dye under the skin did nothing to dull the pain during endless hours of tattooing.

But what did pain and infection and possible death matter when a person was marking their flesh to honor their gods, their culture, their ohana? And how could any leader prove their worth without enduring and surviving such agonizing marking?

When the old ways were abandoned along with the old gods, and the minions of the new God discouraged such pagan practices as tatau, body adornment lost its significance and faded throughout Polynesia.

But Polynesians are recovering a sense of pride in their culture, and nowhere is that more visible than in tattooing. Anona and Nappy Napoleon watched in fascination as they attended outrigger canoe-paddling competitions in Tahiti and New Zealand during the past 15 years and saw more and more traditional designs emerging on the skins of Tahitians, Marquesans and Maori.

Surfers on the mainland are intrigued by the rising tide of tattooing among their fellow wave riders, but many are unwilling to join the inkfest.

World longboard champion Colin McPhillips has watched in amazement as the Southern California lineup has started to fill with tattooed surfers, including many of his friends. McPhillips was intrigued, but not tempted to join them. "I like some of the ones I see on people, but I'd never get one. The fact that you can't wash it off makes it so permanent."

When his younger brother came home with a tattoo, McPhillips' reaction was immediate and disapproving. "I asked him 'What the hell did you do that for?'

"I think those Polynesian ones look pretty cool, it's cool for them, but I can't imagine a haole showing up with that on them."

For many surfers, tattoos are a family affair that pay homage to the larger Polynesian family, and the more intimate ohana. And each family reacts differently to the subject of body art.

None of Nappy and Anona Napoleon's five sons and 11 grandchildren has tattoos, and the family elders gently discourage such activity.

"Our next-door neighbor had a tattoo on his leg, and decided he wanted it off," says Anona. "He was telling me about the pain involved, and that he wished he had never done it. I have told my sons, 'It's your body, do what you want.' Then I tell them to go next door and talk to big Mike."

Sunny Kanaiaupuni linked two proud Hawaiian families when she married Rusty Keaulana, but she has no interest in marking her body to commemorate the union of the clans. "For me, it comes down to pain. I don't like needles," she says. "The only tattoo I have is from the reef at Makaha."

Rusty Keaulana created his first tattoo at age 11 when he and sister Jodi were playing around with a needle and thread. He proudly sports that humble "R" on his hand, as well the Keaulana name more elegantly emblazoned across his back, along with "Russ-K Makaha" and his Tahitian honu.

"Everyone has their own reason for getting them, family tattoos, their name, a loved one. For me, I made it as a family thing, and my business. I'm stoked with my tattoos, they all mean something."

With his blond hair and blue eyes, it's apparent that North Shore surfer Kolohe Blomfield's haole genes kicked okole in the battle to determine his appearance. But he has found a splendid way to honor his Hawaiian ancestry.

Kolohe's wife, Lynn, is a longtime friend of cultural anthropologist Tricia Allen, who has brought Polynesian tattoo artists throughout the Pacific historical material from the Bishop Museum to help them create traditional body art from their island groups.

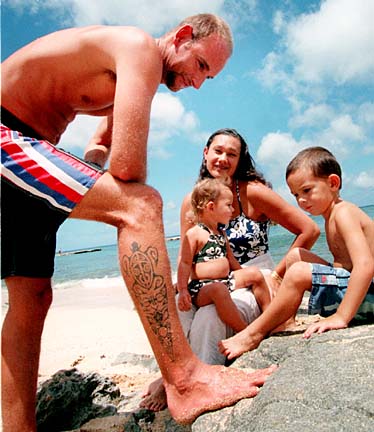

Kolohe and Lynn Blomfield wanted something special to symbolize their family and each member's personality, so they had Allen customize some of her traditional patterns.

The stunning result is a portrait that becomes more intricate as the family grows. A honu is special to Kolohe and his father, the late black coral diver Harold Blomfield. On the honu's back are tiki for Kolohe's mother and father, and two wave crests. An iwa bird represents Lynn, who is a flight attendant, and a smaller honu is for their son. Its shell is blank, so they can embellish it with art as he reveals more of his personality.

Tying it all together is a Marquesan-style hibiscus for their daughter, representing her softness and beauty. Kolohe's mother is enchanted with the tattoo. "I really love the Polynesian aspect of it, because he is Hawaiian, even though he looks haole."

Big Island surfer Conan Hayes chose to honor his mother with an exquisite airbrush-style tattoo of her baby picture, which looks startlingly like he must have appeared as an infant.

Makaha surfer Desiree DeSoto is an anomaly in her ohana, where most members from her grandmother on down proudly carry their family crest inked on their flesh. "At this point in my life, I'm not ready," she says.

"I love the way they look, but it's not for me. Our aumakua is the pueo, and our crest also has my grandmother's name in it, and the symbol of the rainbow. My dad and his brother love to ride motorcycles and surf, so they have mountain and ocean in it.

"When the time comes to get it, I'll know it. I'll be 100 percent with it."

Desiree is, however, delighted with her cousin Duane DeSoto's tapestry of tattoos, which are beautifully rendered visions of his personal history, family life and ancestral connections.

DeSoto got his second tattoo when he was 18 after researching the symbolism and selecting just the right artist, Poot, a Belgian inker who was working in Hollywood at the time. Stretching across his lower back is an owl in the Northwest American Indian style.

"This combines a lot of meaning for me," DeSoto says. "Our Indian and Hawaiian heritage, and pueo is our family aumakua and is in my brother's and sister's names."

His most recent tattoo marks another trip to Tahiti, with a taro plant rooted on his heel and growing up his ankle and calf with piko, stalk and leaves. "It's the basic building blocks of Hawaiian society, it's the complete ohana.

"I go all over the world and have to represent myself with my tattoos. It's who I am. They are rites of passage, to say this is where I'm from. For my next tattoos, I'll wait until I'm inspired. They have to be meaningful to me, celebrations of my children, celebrations of my wife."

While paddling through the lineup in the surf it's easy to see that the tattoo revival is a youth movement. The kids are sporting all the shiny new images, while the veterans carry faded reminders of their youth. And the impetuousness of youth is likely to tow the kids onto waves of enthusiasm that could leave them with regrets once the excitement recedes.

"I feel pain for them because it must have been painful to put it on, and if at one point they want to take it off, there will be more pain," says Anona Napoleon.

Desiree DeSoto is emphatic in offering insight to youngsters on the wisdom of tattooing. "When I see people with hateful or racist tattoos, I confront them. Some people might get something tattooed on them and they don't know what it means, like gang symbols, and get into trouble. You should research it before you get it done."

Blomfield's father had some amazing tattoos, including a dragon by the legendary Sailor Jerry. After watching his father get additions to his personal tattoo gallery over the years, the teen-aged Kolohe told his mother that he wanted a tattoo.

She cautioned him to wait until he was older, because he might change his mind. "It was like a coming of age when he finally got his first tattoo," his mother says. "He waited for the right inspiration and the right tattoo artist, and he thought of the special meaning of it."

Although he acquired his first tattoo at an early age, DeSoto is a big proponent of patience. "You have your whole life to wait for the right design," he says.

One of the benefits of a long life is that eventually you see everything come back in style. Anona Napoleon has watched fads and fashions come and go during her decades spent happily in the embrace of the ocean, and while she missed the original golden age of Polynesian tattooing, she is witnessing its renaissance with keen interest.

"It's so amazing. The first tattoo I saw was just 'Mother' on a beachboy's shoulder, and now they have their mother's picture as a baby on their arm."

Click for online

calendars and events.