Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

Like many longline fishermen, 37-year-old Bryan Aasted is a second-generation seaman.

'When the fishing is good,

it's good. There's nothing better'

By Steve Murray

Star-BulletinBorn and raised in Hawaii, he began fishing with his father, a National Marine Fisheries Service gear specialist, when he was 13.

Over the next 24 years he has fished for everything from lobster to tuna, from Hawaii to Alaska. He has been longline fishing exclusively since 1985.

On July 6, Aasted hurried out to sea trying to get in one last trip before a court order drastically limiting longlining was to take effect August 5.

"After this I am out of a job," he says. "I don't know what I'll do."

Considering the small fortune it takes to begin longlining, you might think Aasted and others like him are in pretty good shape financially. He says this is far from the truth. "I have a 10-year-old truck and a 30-year-old boat," he said. "It's just a living. It's nothing great."But it's an occupation he prefers to the "on-land" jobs he's tried. It suits him, he says, because "I'm a local boy. Hawaii is my home."

Aasted and his two-man crew make about 12 trips a year -- about average for a longliner. While motoring a few hundred miles from shore, the crew prepares for anywhere from five days to three weeks of fishing. They check fishing lines for damage and make sure the 1,700 hooks are clean and sharp.

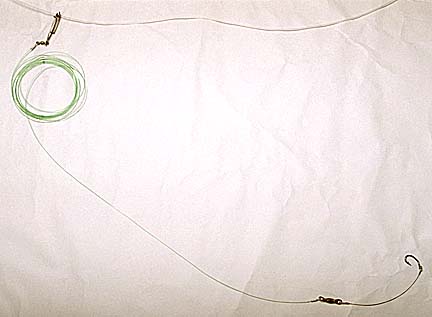

Then it's up to the captain to find the fish. Aasted takes into account past fishing trips, air and water temperatures, currents, and information from other boats that have been out recently.When the crew arrives at the chosen fishing grounds, they ready the gear. About 7:30 a.m. they begin the slow task of putting out between 32 and 35 miles of 1,000-pound-test line. It takes about four hours to carefully lay out the main line, which is fed from a giant spool on deck. The line handlers attach a hook, baited with mackerel, about every 150 feet. Dispersed along the length of the main line are five radio buoys that will allow the captain to locate the line when it is time to retrieve it -- hopefully with plenty of fish attached. Orange floats are also used between the radio buoys to control line depth. When fishing for tuna, as Aasted does, the hooks are generally set to a depth ranging from 150 to 600 feet.

A typical "set" of the line may yield about 8 to 12 tuna and 5 to 10 other types of fish. The other fish caught are usually mahimahi, marlin, moonfish, ono and other deep water varieties. The non-tuna catches are kept and sold at auction. Undersize tuna -- those less than 40 pounds -- are thrown back to grow bigger.

A lawsuit filed by the Center for Marine Conservation and the Turtle Island Restoration Network against the National Marine Fisheries Service led to recent restrictions on longlining imposed by U.S. District Judge David Ezra. The environmental organizations say longlining is killing endangered sea turtles. Like most longline fishermen, Aasted doesn't agree.

"In fifteen years I have seen only one turtle," he said. "It was hooked by its shell. We removed the hook and he swam away."

At about noon, when all the line is out, it's down time. During the seven or eight hours the line is "soaking", the crew eats and gets some rest. However, one person must be awake at all times, to keep a 24-hour watch from the bridge of the boat. Getting as much sleep as possible is necessary because once they start bringing in the lines, it normally takes 12 to 20 hours to finish the job.A major concern among fishermen is the proposed reduction of "soak time" to just four hours in Judge Ezra's ruling. Aasted says cutting the soak time could increase the likelihood of injuries, because "sometimes it is the only time the crew can get any sleep."

Shortly after the sun has gone down, it's time to bring in the lines. Aasted must perform three jobs at once: steering the boat, controlling its speed and handling the line as it comes in.

This part of the operation is the most dangerous. Bringing in a new hook every eight seconds for a dozen hours provides even the most careful crew with many opportunities to catch a large, sharp hook in the hand, arm or even in their side.

When there's a fish on one of the hooks, the boat is stopped. The fish is hoisted on deck and the hook gently removed. Working with a fish that averages 90 to 100 pounds and stretches about 4 feet 6 inches long is not an easy task.

Dressed in yellow rubber overalls and heavy boots, a crewman hits the fish's head with a large spike that instantly kills it. The fish is then bled and washed with sea water to eliminate bacterial growth. When thoroughly cleaned, the fish is iced down in the hold.

At the same time the fish are being brought on the ship, the $16,000-worth of line is checked for any damage. Aasted says the inspections are important because a damaged line could mean losing a fish that may bring as much as $1,000.

Aasted counts 1,500 to 2,000 pounds a day of quality fish as good fishing. He says every four or five years he hits a 10,000-pound day.

"That's when you're glad to be a fisherman," he enthuses.

Aasted always hopes a trip will fill the 20,000-pound iced capacity of his boat. He says the break-even point for the trip is between 12,000 and 15,000 pounds of fish.

It's time to head home when the hold is full or about 10 days have elapsed since the majority of fish were caught, whichever comes first. The whole crew hopes for a seller's market because the crew is paid a percentage of the boat's overall profit for the trip. It's a system that hasn't changed since whaling days.

"Sometimes we go out and no one makes a cent," he said. But the call of the sea is strong and "when the fishing is good, it's good. There's nothing better."