Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

Keaau: An

education town

Four new schools give

post-sugar-era residents a

rekindled sense of prideChosen area met several criteria

By Crystal Kua

Designed for optimal learning

Immersed in sharing a culture

Star-BulletinWHEN Rachel Rechtman was a first-grade student in Keaau last year, she was taught in a stuffy, century-old classroom that had witnessed the time when sugar was king in her Big Island community.

Sugar hasn't reigned there for years, and Keaau's future was uncertain. But now residents are hopeful because they see a new crop for the former plantation town: children's minds. In the past five years, four schools have been built or are being planned. For Rachel, that means second grade is being spent in a shiny new school complete with computers and air conditioning.

"Some people are calling Keaau an education town," said Bob Saunders, president of W.H. Shipman Ltd., which owns most of the land in and around the community. "People I talk to are proud."Residents to varying degrees think the rapid blossoming of education in the area could provide a much needed catalyst for change.

"We look forward to all these schools," said Gladys Nakamura, 76, a Keaau native. "Families will be moving in and the land is still the cheapest in the state of Hawaii. Everything is a plus. We look forward to a good future."

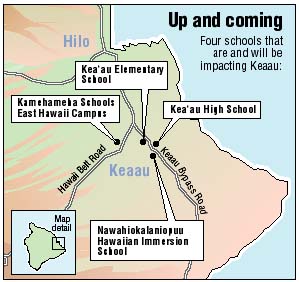

The schools are:

Kea'au Elementary School. The school opened last year and allowed elementary and middle-school students to be placed on separate campuses. The old Keaau School, which housed students from kindergarten to eighth grade, is now used exclusively by middle-school students.

Kea'au High School. The school was built to relieve overcrowding at Waiakea High School in Hilo. It opened in January, and will add a grade level each year for the next three years.

Kamehameha Schools. The East Hawaii campus of the private school for students of Hawaiian ancestry will begin moving from Keaukaha in Hilo to a permanent site in Keaau in 2001. It eventually will serve students K-12.

Nawahiokalaniopuu. The public Hawaiian language immersion school opened in 1995, and is receiving national and international recognition for revitalizing the Hawaiian language and culture.

Affordable homes

For most of this century, Keaau's lifestyle revolved around the sugar plantation that eventually became Puna Sugar Co. The old Keaau School, in fact, was built in 1900 by the plantation, which initially called it Olaa School. Puna Sugar started shutting down in 1982, leaving 500 people jobless and wondering about their children's future.Now thoughts are more upbeat. "I think people have moved to Puna because of the affordability -- they can build a home -- and the schools will add more value in the area," said Carl Okuyama, chairman and chief executive officer of Sure Save Supermarkets, the area's largest store.

Barbara Robertson, Kamehameha Schools East Hawaii principal, points out that "people will have a choice on where they want to send their children, and that's an advantage."

There are good reasons why the schools would choose Keaau. Land is available and relatively cheap.

Its location about 10 miles south of Hilo makes it convenient from most of East Hawaii. The University of Hawaii at Hilo is close by. And the Puna District of the Big Island offers opportunities for a diverse range of studies: volcanology, marine science, astronomy, agriculture, aquaculture.The schools could give a distinct identity to Keaau, long considered a Hilo bedroom community. "Shipman's vision is more of a self-contained community," Saunders said. "Public and private educational institutions are part of the mix."

State Sen. Andy Levin (D, Puna) said the social impact "is something we can look forward to."

"Instead of being a suburb of Hilo, it will be a town in its own right," he said.

"Just the fact that you are going to Kea'au High School or you're now going to the Kamehameha Schools in Keaau, you enhance the identity."

'Working together'

Establishing quality schools also means students can stay on the Big Island and get a top-notch education."We've been taking the cream of the crop and shipping them off to Honolulu," Levin said. The schools themselves may find it advantageous to be close to one another, and able to provide mutual support.

"What I would like to see is us working together and sharing facilities," Kea'au High School Principal Peg O'Brien said. "We're hoping to do that."

For all the promise, there is also a concern -- namely, traffic. Congestion has long been a sore point among the town's residents, and the schools when fully running could have a combined enrollment of more than 3,300 students. A bypass highway is being built, but two proposed shopping centers could add to the problem."Traffic -- that's the biggest complaint," said Nakamura, the unofficial mayor of Keaau. "Keaau not comin' country anymore."

Levin, co-chair of the Senate Ways and Means Committee, said he is working with the state Transportation Department to resolve community concerns.

And a big question remains: What will the students do after they finish schooling? The Big Island typically has one of the higher unemployment rates among the major islands, and while the schools may provide a boost, a quick fix is unlikely. Bob Rechtman, Rachel's father and president of the Keaau Elementary School PTSA, is among those who are cautious.

"I think (the schools) are going to have a significant impact on the community. It's providing a sense of pride for the students as well as parents," he said. "But I don't see schools as the salvation."

Chosen area met

By Crystal Kua

several criteria

Star-BulletinFor Kamehameha Schools, the key factors in choosing a site for a permanent East Hawaii campus were finding enough land, and finding land that was centrally located to serve day students from Kalopa to the north and Naalehu to the south.

It chose Keaau."This will give us more space," said Principal Barbara Robertson.

The K-12 school will be built on 300 acres of land purchased from W.H. Shipman Ltd. Ground-breaking is scheduled for this summer, and the school hopes to open for grades 6-8 in the fall of 2001. A thousand students are expected within five years.

Aside from classrooms, a gymnasium, pool and playing fields are in the works.

The school plans to take advantage of the resources available on the Big Island, Robertson said.

"We have many places to learn from, and that's the advantage of having a school there, the accessibility of resources," she said. "Everything is minutes away. Astronomy is right up the Saddle Road, volcanoes are nearby, the university is there."

Robertson said the school will offer a broad spectrum of courses, including college preparatory.

"They will have an education that recognizes their culture ... and it will also prepare them for life, and to make choices on what they would like to be and what they would like to do," she said.

Campuses designed for

By Crystal Kua

optimal learning

Star-BulletinThe roofs are corrugated iron and the outside walls are painted in earth tones. The buildings have the feel of a village -- which is exactly the intent.

In a time of anonymous malls and cookie-cutter chain stores, the designers of Kea'au Elementary and Kea'au High school were inspired by a basic principle: sense of place. The schools recall Kea'au's plantation past and are like villages within a larger village, in keeping with community desires.

"They wanted the school to look like a village," Theron Nichols, a state Department of Education facilities planner, said of the high schools. "It reads as individual buildings with a village appearance. ... There's also a lot of common things, so it does read as a unified campus."

And, all analysis aside, "It's a nice place to walk."

The high school opened its doors this school year to 280 freshman Cougars, after completion of a $35 million first increment. When fully built in three years at a total estimated cost of $75 million, the 55-acre campus is projected to have between 1,200 and 1,400 students.

Kea'au Elementary was completed last month, although the first classes were welcomed in the 1998 school year. It has just under 900 students K-5.

The schools not only blend with the architecture of the area's homes and businesses, they also adapt to the area itself. Walkways and a play court at the high school, for instance, are covered to protect students from Keaau's frequent rains. At the elementary schools, deeper walkways give children an outdoor space near the classrooms for activities like painting or reading.

Amenities will not be lacking. The high school plans to have a stadium and gymnasium. It already has individual restrooms for students, which should help reduce the intimidation, safety and security problems found in larger, common restrooms with multiple stalls.

Flexibility also was a consideration. Science laboratories, for example, are clustered together and apart from lecture rooms, which can be used to teach subjects other than science.

"This is going to be a first-class high school," District Superintendent Dan Sakai told Board of Education members during a tour. "It's pretty much the best you can get."

Some shakedown may be needed. Traffic flow was a problem at the elementary school. With no on-street parking available, long lines of cars backed up along the highway in front as parents shuttled their children. The school is working on a solution.

But parents and other Keaau residents are enthused.

"The community is very excited about these schools," Nichols said. "I hope there is a lot of good design in them so people will say, 'Hey, this is my school and I'm proud of it.'"

Bob Rechtman, president of the Kea'au Elementary PTSA, said his second-grade daughter, Rachel, already is sold.

"She loves her new school," he said. And the mere fact of newness means the schools can pursue their prime mission: teaching.

"Other schools are worried about their facilities," he said. "This isn't a concern for a brand-new school. They can now focus on education. They don't have to worry that the building is going to fall down."

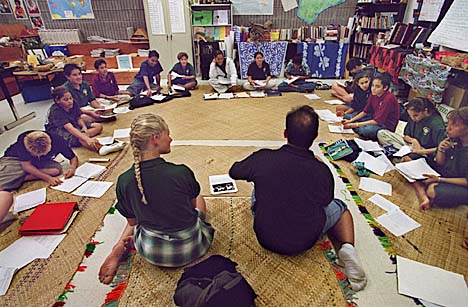

Scenes at the Hawaiian immersion school Nawahiokalaniopuu

Immersed in

By Crystal Kua

sharing a culture

Star-BulletinMORNING rain sprinkles on the faces of Kalei Victor and Mele Kahananui as the two 10th-graders solemnly escort a visitor to their school's entrance.

A chant of welcome arises from a gathering of fellow students in the melodic cadence of the Hawaiian language.

From the gathering, social studies teacher Lehua Veincent steps forward and recalls a time not too long ago when his ancestors were prohibited from speaking their native tongue.

But now, he declares, the language is flourishing -- here, in the halls of Nawahiokalaniopuu.

Nawahiokalaniopuu, called Nawahi for short, is a Hawaiian language immersion school in Keaau that understands its greater purpose for being.

"The word 'school' doesn't describe us," said administrator Kauanoe Kamana. "People think we're a language school, but we use the Hawaiian language to strengthen the Hawaiian culture."Named for the first principal of a Hilo boarding school in the mid-1800s, Nawahi's 84 students in grades 7-12 use the Hawaiian language and culture while learning subjects such as science, math, social studies and English. The first class graduated last year.

It has won recognition for its efforts to revitalize a dying language, featured in a Washington Post article last year and a Los Angeles Times story last month.

Nawahi officially falls under the state Department of Education, but is considered a laboratory school of the College of Hawaiian Language at the University of Hawaii-Hilo.

Since opening five years ago, it has built up its 10-acre campus beyond the original buildings -- classrooms, administrative offices, a dormitory and gymnasium -- to include gardens and aquaculture tanks, greenhouses, livestock stables and pens, an imu or underground oven, and a solar-power generator.The structures reflect Nawahi's diversified approach to education, and its commitment to keeping diversely talented students on the diploma track.

Senior Darcy Perez, for instance, was sitting one day at a picnic bench under a gazebo, wrestling with math problems while classmates were at UH-Hilo taking college courses. He acknowledged academics may not be for him, and credited his teachers for encouraging him to persevere.

"They make sure you can graduate," he said. "Otherwise, I would be with my other friends, still in the ninth grade."

Perez perked up, though, when he turned to his duties as caretaker of the aquaculture tanks, next to the gazebo. He fed tilapia and Chinese catfish, demonstrated how he checks the water's pH levels, and talked about learning while keeping his culture alive."I'm taking care of animals, living off the land, raising food to eat," he said, flashing a broad smile.

Namaka Rawlins, executive director of 'Aha Punana Leo, a nonprofit group that supports Hawaiian language programs, said Perez is an example of how cultural identity can play a large role in helping youths realize their full potential.

And in the sharing spirit of the Hawaiian culture, the school said an alliance between 'Aha Punana Leo, UH-Hilo's Hawaiian language college and the DOE -- particularly Hilo High School Principal John Masuhara -- helps it to do more with less.

Rawlins agreed.

"We work together to make resources more productive," she said.