Saturday, October 23, 1999

After two years of legal

By Gladys Brandt, Samuel P. King,

investigations, changing policies

and reforms are beginning to heal

Bishop Estate's broken trust

Walter Heen and Randall Roth

Authors of "Broken Trust"Written with inspiration from the late Monsignor Charles Kekumano

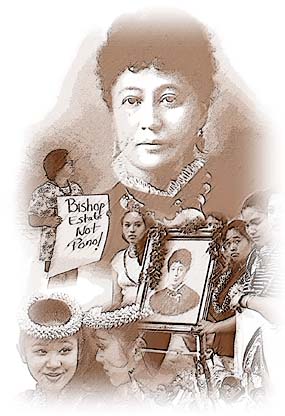

It began with a simple request. In 1997, a group of concerned Hawaiians asked for a meeting to air complaints about the actions of certain Bishop Estate trustees. Two years later, the result has been major changes in the governance of the estate, the fortunes and reputations of the estate's trustees and the procedures of the state judiciary. More changes are in the making. Most observers view the changes so far as positive, but the quality of change will continue to be positive only if we remember the past and remain vigilant.

A look back

British explorer Captain James Cook estimated a native population of 300,000, or more, when he happened upon Hawaii in 1778. By 1831, the year of Princess Bernice Pauahi's birth, the number had declined to 130,000. Just 52 years later, in 1883, the year this last descendant of Kamehameha the Great wrote her will, the native population barely exceeded 44,000. Her race was not just in decline, but quickly on its way to extinction.How insightful yet logical that she would bequeath the bulk of her immense estate in trust, so the educational opportunity and religion that gave her strength and hope could do the same for countless others. Specifically, she instructed trustees "to erect and maintain in the Hawaiian Islands two schools, each for boarding and day scholars, one for boys and one for girls, to be known as, and called the Kamehameha Schools."

They would be run by "persons of the Protestant religion," and dedicated to producing "good and industrious men and women." The princess -- once described as "the brightest, the gentlest and the purest of (Hawaii's) daughters"-- who had no children of her own, effectively adopted the children of Hawaii.

While the letter of the will does not exclude non-Hawaiian boys and girls as direct beneficiaries of her largess, common sense dictates that Princess Pauahi intended primarily to benefit children of Hawaiian ancestry for as long as a special need exists. This intention was confirmed by her husband, Charles Reed Bishop. In a 1901 letter to Samuel Damon, he wrote:"...it was intended that the Hawaiians having aboriginal blood would have preference, provided that those of suitable age, health, character and intellect should apply in numbers sufficient to make up a good school...The Schools were intended to be perpetual, and as it was impossible to tell how many boys and girls of aboriginal blood would in the beginning or thereafter qualify and apply for admissions, those of other races were not barred or excluded."

The will authorizes the trustees "to regulate the admission of pupils," and trustees have used that power to limit admission to boys and girls with some quantum of Hawaiian blood, thus honoring the intent, or "spirit," of the princess' will.

Even so, the benefits of this legacy have touched only a small percentage of the school-age Hawaiian population.

Land-based trust

One reason for this is that the initial trust corpus consisted almost entirely of land -- 375,569 acres in all. A substantial infusion of cash and additional land from the princess' widower made it possible for the schools to be built in a matter of years, rather than the decades it would have taken for estate land to generate the needed cash.The letter of the will clearly authorized trustees to sell land as they deemed necessary "for the best interest of (the) estate," but the will also expressed Princess Pauahi's desire that they not sell land. The current inventory of land -- 362,833 acres -- is reasonably close to the original number of 375,569, but well below a peak of 440,184.

Some wonder why Pauahi strongly preferred that the land not be sold. The will of her cousin Lunalilo had actually ordered the sale of his land after his death. Perhaps the princess believed that over time land would maintain what today might be called inflation-adjusted or real value.

Her instruction that income be expended annually suggests that she wanted maximum sustainable spending. Her goal was "good and industrious men and women," not accumulation of money for the sake of accumulation.

Will not always followed

Ironically, the ousted trustees now accuse the attorney general, master, probate judge, IRS and others of trying to destroy the will. The truth is that these and other trustees deviated from the will on numerous occasions. For example, the will clearly calls for separate schools, one for boys and one for girls. Yet many years ago trustees got permission to combine them. Princess Pauahi also wanted the schools' curriculum to be primarily vocational and only secondarily college preparatory: "I desire instruction in the higher branches to be subsidiary..." That, too, has not been honored for many years.If the princess were here today, she probably would agree with those decisions, just as she probably would favor today's policy of giving college students of Hawaiian ancestry financial assistance from her trust. The point is that these decisions, for better or worse, go directly against the letter of the will.

Provisions of the will that have been violated over the years include a requirement that a detailed list of assets and expenditures be published each year in a Honolulu newspaper (this hasn't been done for many years) and that income not be accumulated indefinitely. (The recently ousted trustees not only accumulated $351 million of income, they transferred it to corpus and actively hid this breach from the probate court.)A requirement that only Protestants serve as teachers was declared invalid by a federal court in 1993. The instruction that all trustees be Protestant has not been honored since 1994 when a judicial conduct commission reminded the justices that they could not discriminate on the basis of religion, even when functioning in an individual capacity.

The ousted trustees and the Supreme Court justices who appointed them followed the will when doing so served their purposes, but deviated when it did not.

Holding trustees accountable

No individual has a right to benefit personally from a charitable trust, neither does any ordinary citizen or any group of individuals have the legal standing of a beneficiary. When trustees of charitable trusts deviate from the governing instrument or breach other fiduciary duties, it's primarily the job of the state attorney general to bring this to the probate court's attention. This centuries-old legal arrangement is called parens patriae.The probate court also can take action sua sponte (on its own), based on its review of an annual master's report.

For whatever reason, a succession of probate judges, masters and attorneys general failed as watchdogs of Bishop Estate actions for many years. This enabled arrogant trustees to breach their fiduciary duties with impunity.

Things began to change only when Kamehameha students, parents, alumni and faculty began to question the highly intrusive manner in which the trustees were managing the school. In the typical Hawaiian manner, these parties, individually and collectively, quietly and unobtrusively attempted to achieve pono at the school.

Only when their efforts were frustrated by an obdurate majority of the trustees did they march in protest from Mauna 'Ala to the Supreme Court building. An overwhelming sense of duty to Princess Pauahi and the children pushed them forward, despite the likelihood of retaliation by embarrassed trustees.

Inspired by the marchers' passion and courage, the four of us, along with Monsignor Charles Kekumano, decided to point out that more was broken than even the marchers might have realized. Evidence strongly suggested that the selection of Supreme Court justices had been influenced by the justices' role in selecting Bishop Estate trustees. The end result was a tainted judiciary and a politicized Bishop Estate.

People who didn't understand what it means to be a trustee were on the verge of losing the estate's tax-exempt status, not to mention the confidence of the Hawaiian community. By pointing out all of this, we hoped to spark needed reform within both institutions.

Writing "Broken Trust" was easy compared to getting it published in the Honolulu Advertiser. Editor Jim Gatti gave us the runaround for weeks despite being told by members of his staff that it was a "blockbuster" and by his predecessor George Chaplin that the essay was sure to be "the biggest thing to hit Hawaii since statehood." After three weeks of unsuccessful attempts to get the go-ahead from Gatti, we took it across the hall to the Star-Bulletin, which published it the next day.

That was Saturday, Aug. 9, 1997. Three days later, Governor Cayetano called for an investigation of the trustees.

Reaction to "Broken Trust"

The state Supreme Court justices' initial response to "Broken Trust" was to question our facts and motives. The justices, who, according to Pauahi's will, appointed the Bishop Estate trustees, also swore never to turn their backs on their "sacred duty to Ke alii Pauahi."Indeed, during the next few months they had secret communications with the trustees and took no action on requests that they recuse themselves from appeals involving the trustees they had selected.

Attorney General Margery Bronster heeded the governor's call for an investigation, and quickly proved to be fiercely independent, uncowed by the trustees or their lead attorney. She also told the justices that unless they agreed to be questioned separately, she would issue subpoenas and take their depositions. According to two separate sources, all five justices refused, insisting that she talk to all of them at the same time, or not at all.

Patrick Yim, deputized by the probate court so that he could determine the nature and extent of the problems on campus, submitted a report that supported trustee Oswald Stender's claims about the adverse impact trustee Lokelani Lindsey was having on the school's administrative staff, faculty and students. Yim also reported board-wide negligence: "Though the alarms were being sounded by the actions of one of the trustees, the others either ignored it, or failed to grasp the consequences of it."

By far the greatest role in the removal of trustees and reform of the estate was played by the court-appointed master, Colbert Matsumoto. His reports to the court were absolutely brilliant in their precision and clarity.

It was just a few days after the issuance of Matsumoto's first report that the justices changed their tune. Without mentioning their earlier statements to the contrary, or explaining the timing, all five publicly pledged not to hear any of the many appeals already being generated by the attorney general's investigation. And all but Justice Robert Klein added that they would have nothing to do with the selection of future Bishop Estate trustees.

Judiciary moves slowly

Probate Judge Colleen Hirai was asked by the attorney general to remove the trustees temporarily but she declined to say yes or no without a full-blown trial. Legal matters only began to move when Judge Kevin Chang was assigned to the probate calendar in early 1999. While he didn't actually take the question of removal away from Hirai, he did the next best thing. Pointing to Matsumoto's recommendation, Chang ruled that the trustees had a conflict of interest in the on-going IRS audit. He then appointed five special-purpose trustees to represent the estate's interests in that audit.These five were told by IRS senior personnel that the estate's tax-exempt status was in jeopardy if the five sitting trustees weren't removed permanently. Information discovered over the course of the four-year audit convinced the IRS that the sitting trustees could not be trusted.

Chang immediately ordered the sitting trustees to show cause as to why they shouldn't be removed as had been recommended by Matsumoto. He did so because of the IRS threat, but also because the trustees deliberately had ignored stipulated court orders. One such order was that the trustees develop and implement a chief executive officer business structure, and hire a CEO.

Judge Chang temporarily replaced all five trustees with the special-purpose trustees the day after another judge removed Lindsey permanently. Since then, Stender and Gerard Jervis have resigned.

As a practical matter, all five of the former trustees are gone for good. Henry Peters, Richard Wong and Lindsey continue to battle in court, but the case for their permanent removal is overwhelming. The foreseeable future of the former trustees will be spent defending against the attempts of various bodies to assess them with millions in surcharges, taxes, intermediate sanctions, damages and ordered reimbursements to the trust.

Settlement agreement

Judge Chang has been asked to approve of a settlement tentatively agreed to by both the IRS and interim trustees. It would require that the estate pay about $13 million in taxes and interest, which is manini compared to the $750 million estimated cost of losing tax-exempt status. It also is much smaller than the amount likely to be assessed at the for-profit subsidiary level. That set of issues is being negotiated separately.Ousted trustees and their followers now attack the proposed settlement agreement because it calls for the permanent removal of all the former trustees. They argue that this amounts to the IRS trying to take over the job of the probate court. They also contend that the agreement will strip trustees of power and lead to the hiring of a mainland CEO who will sell the land and destroy the estate. According to them, Princess Pauahi wanted trustees to function as highly paid, full-time CEOs.

All of this is nonsense. Pauahi's will says nothing about compensation. At the time it was written, the law and expectation was that trustees of charitable trusts would serve without any compensation. The will also says nothing about the need for trustees to devote full-time efforts to managing the estate. None of the princess' handpicked trustees worked full time on the trust.

The former trustees agreed more than a year ago to hire a CEO to run estate operations on a day-to-day basis. The new CEO may or may not come from outside Hawaii, but he or she clearly will take marching orders from the estate's trustees. If the CEO does not do the job the way they want it done, he or she will be dismissed. It's just that simple.

As for the contention that a CEO will sell land, it must be remembered that this is a trust, not a corporation. The land is owned by the trustees, not some bloodless legal entity. If it's to be sold, it will be by trustees, not an employee of theirs.

The proposed settlement includes the interim trustees' agreement to increase significantly the amount of money spent each year educating Hawaii children. The suggestion that this so-called spending plan would necessitate the sale of land is simply wrong. The proposal calls for a flexible "unitrust" approach. Rather than spend income, as that term currently is defined by Hawaii's Principal & Income Act, the trustees would use their best efforts to spend amounts that over time would average 4 percent of a base amount. In anyone year, the percentage might be as low as 21/2 percent, or as high as 6 percent, according to the plan.

Other public charities typically spend more than 4 percent of their corpus. Harvard's target is 41/2 percent; Yale's is 5 percent. Private charities, by comparison, are required to expend a minimum of 5 percent each year. Few of these are "land-based," but that doesn't really distinguish them from the Bishop Estate because of a unique feature of the proposed spending plan which excludes from the base the value of all land classified as agriculture or conservation.

The trustees would have to spend only whatever net income might be generated by these 362,000 acres of land. Residential and commercial real estate would be included in the 4 percent calculation, but because it is subject to leases that generally are renegotiated regularly, it reasonably can be expected always to yield more than 4 percent of current value.

The proposed spending policy is in perfect harmony with the spirit of Pauahi's will. She wanted land to be retained, if possible, and she wanted maximum sustainable spending. That's what this approach is all about.

Trustee selection

At the time of Princess Pauahi's death, justices of the Supreme Court of the Kingdom of Hawaii had jurisdiction over wills and trusts. Official duties included the selection of trustees. More importantly, the princess' will specifically empowered them to select her replacement trustees. Presumably, she wanted group decisions by respected and knowledgeable individuals who themselves had been selected by members of her ohana. That's how justices were selected in those days.Now that four of the current Supreme Court justices have stated that they will not select new trustees, the probate court must approve of a process that will honor the spirit of Princess Pauahi's will.

People who call for selection by a single justice, retired justices or judges of the intermediate court of appeals, effectively are calling for a rewriting of the will. That's unnecessary. Since the probate court already has jurisdiction, the probate judge has the power to appoint new trustees without doing damage to the letter of the will.

To honor its spirit, he or she can allow the actual selection to be made by majority vote of a panel of respected individuals. Just as Supreme Court justices at the time of Princess Pauahi's death were chosen by members of her ohana, many if not most members of future selection panels should come from Pauahi's adopted ohana. This would include Kamehameha alumni, students, parents, teachers and staff.

The work of the interim trustees should be greatly facilitated because of the existing court order to develop and implement a CEO management structure in which trustees can function mainly as policy makers. With such a format, the necessary qualifications to be a trustee can change considerably. That, combined with the fact that trustees would not be required to quit their current jobs, should result in an abundance of qualified candidates. New trustees should be expected to put far more resources into educating children.

We all benefit

The Bishop Estate is and must remain one of the most valued assets of our community. The education provided to young people of Hawaiian ancestry by the Kamehameha Schools benefits all of us as well as them. It gives them the knowledge and skills necessary to compete in the modern world and makes them an important part of the work force we need to sustain our islands' economy.Additionally, the grounding in their native culture received at the school and spread by them throughout the community preserves for all of us the once-endangered heritage of their ancestors.

In that sense we are all beneficiaries of the princess' wisdom and generosity. For these reasons, and many more, we all share in the need to preserve the vision and the legacy of the princess.

Problems at the Bishop Estate are being resolved. This is happening only because good and industrious men and women stood up to trustees who didn't understand the meaning of stewardship. It is fitting that the direct inheritors of Princess Pauahi's legacy are now its protectors. The princess would be proud.

Imua Kamehameha.

Margery Bronster The investigators

Former Attorney General

Many believe her case against the trustees cost Bronster her job.Colbert Matsumoto

Court-appointed Master

His brutal assessment of estate's management fueled inquiries.

Lokelani Lindsey The ousted trustees

Complaints about her management of schools launched the controversy.Henry Peters

Maintains that trustees' leadership made estate more prosperous than ever before.Richard Wong

Staunch critic of the investigation who is still fighting ouster.Oswald Stender

He tried to reform estate policies and sued for Lindsey's removal.Gerard Jervis

Joined Stender in a successful bid to unseat Lindsey.

Bishop Estate archive