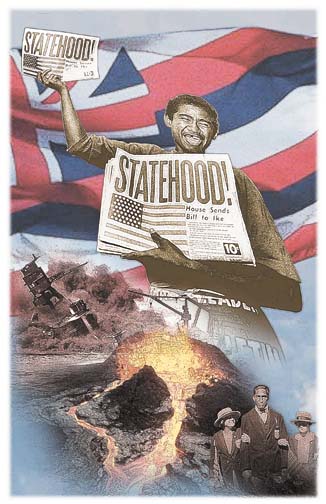

‘The goal was

democracy for all’Statehood was resisted by big business but

By Richard Borreca

others believed it would enhance rights for all

Star-Bulletin

Democracy in Hawaii always has been just a little more dear. Before 1959, politicians in Washington, D.C., picked Hawaii's judges and governors. Voters in Hawaii could not vote for president.

And while Hawaii was a U.S. territory, the islands' freedoms were by no means secure. During World War II, it was placed under martial law -- a fate shared with only a few cities in the South after the Civil War.

Before that, during the uproar over the racially divisive Massie Case, the Navy seriously considered making Hawaii a naval district, under permanent military rule.

So when Congress in mid-March 1959 voted to admit Hawaii as a state, it extended the rights and benefits of full American citizenship to an area that was multi-ethnic, with a non-white majority.

Observers called it the first major piece of civil rights legislation to be passed by the postwar Congress.

"The goal was democracy for all in Hawaii, to give our Asian population a political voice equal to their numbers," said A.A. Smyser, Star-Bulletin contributing editor, who was the paper's political editor during the drive for statehood.Hawaii wanted to become a state before World War II, recalled ILWU union supporter and social worker Ah Quon McElrath.

"In 1933 at McKinley (school), we debated the question of statehood," she said. "We were interested in statehood."

After the war, the ILWU, which was growing into Hawaii's dominant labor union and a major political force, was quick to support the statehood drive.

"We could see where an extension of democracy could be cemented." McElrath said.

"We wanted to extend democracy to an isolated group of islands with a multi-ethnic group. We wanted to be absolutely sure we got that kind of democracy."

Though it later got on the statehood bandwagon, The Honolulu Advertiser in the early postwar years was firmly against it. One front-page editorial, for example, said Hawaii needs statehood "like a cat needs two tails."

The territory's establishment that owned and operated the sugar and pineapple plantations, shipping, and financial institutions saw no benefit in statehood. They already had the influence and power needed to keep their businesses moving smoothly.When U.S. Sen. Guy Cordon of Oregon came to Hawaii to conduct hearings on statehood, it was Walter F. Dillingham, considered the most powerful businessman of his day, who explained why it was not needed.

Dillingham put his elbows on the desk facing Cordon, saying,"this is the way I have talked to every U.S. president since Harding."

The talk impressed Cordon, but in the end he came away saying that while Dillingham may not need representation, the rest of the Territory did.

Business saw the newly expanding power of the labor movement and worried that statehood was just causing more problems.

In 1949, for instance, the ILWU dock strike shut down much of the local economy, to the extent that the action caused Congress to doubt whether Hawaii was ready for statehood.

But Hawaii's cause was championed by its delegates to Congress, first Joseph and Betty Farrington, then John Burns.

Farrington, also publisher of the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, dedicated his life to the statehood effort. It was such a passion that when he proposed marriage to Betty, Farrington warned her that his driving goal was Hawaii's statehood.

It was Farrington who, while in the Territorial Legislature, authored legislation for the Hawaii Equal Rights Commission, which soon became the statehood commission. When he died during his term as delegate to Congress, Betty was elected to his post and continued the fight.But when she was defeated in 1956 by Burns, the statehood drive was again colored by opponents who said Hawaii was filled with Communist Party supporters.

In Congress, Burns lobbied the Southern Democrats in the Senate, who were blocking Hawaii's statehood effort.

"He thrust the Japanese into the limelight, praising their war record, their political skill and their patriotism," Francine du Plessix Gray wrote in the 1970 book "The Sugar-Coated Fortress."

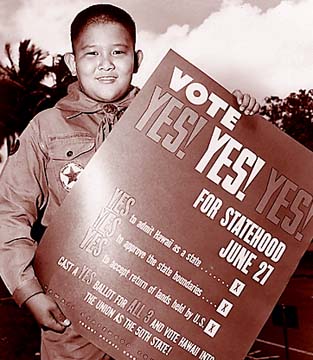

The Hawaii Statehood Commission also was pushing loyalty and American values that cast Hawaii as an extension of Main Street USA. On the cover of its 32-page brochure, sent to members of Congress, the commission featured a picture of morning assembly at Central Intermediate School, captioned, "A thousand young Americans pledge allegiance as the flag is raised in a typical Hawaii school ritual."

Still, the Southern Democrats, lead by Texas Sen. Lyndon Johnson, feared that the multi-ethnic voters in Hawaii would send to Congress representatives and senators opposing segregation.

"Of course, Lyndon Johnson was no friend of statehood," Betty Farrington said in an interview after leaving office.

"There were 22 times when he voted against us, but none of those were on the floor," she recalled. "He'd come into committee and find different and various reasons and ways that he could hold us back.

"And he did. He did everything he could, because he was representing the Southern racial opposition," she said.

Burns, however, worked with both Johnson and Sam Rayburn, the U.S. Speaker of the House, and suggested that Alaska be allowed to become a state first with the guarantee that Hawaii would follow the next year.

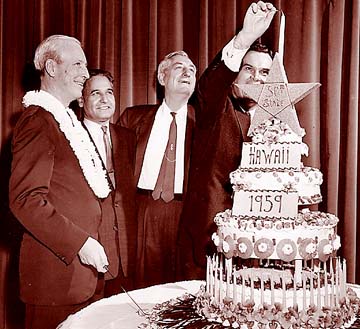

The deal worked. Congress, by mid-March 1959, approved Hawaii's statehood bill - setting up the required plebiscite and statehood elections.

On Aug. 21, 1959 - after a half-century effort tested by ethnic-military tensions, oligarchic power-brokering, political plays and two world wars - a 50-star flag flew over America's newest state for the first time.

The Honolulu Star-Bulletin is counting down to year 2000 with this special series. Each installment will chronicle important eras in Hawaii's history, featuring a timeline of that particular period. Next installment: October 25. About this Series

Series Archive

Project Editor: Lucy Young-Oda

Chief Photographer:Dean Sensui