The story's the thing, but

Thursday: More on "Miss Saigon's" love story.

the musical's special effects

wow audiences tooBy Tim Ryan

Star-BulletinRemember, says "Miss Saigon" production stage manager Mahlon Kruse, "It's the story that drives this show, not the helicopter or Cadillac."

That seems a strange statement from the guy whose responsibility is taking care of the technical and artistic aspects of the acclaimed show.

Along with two assistants, Kruse and crew ensure that every performance looks like all the other "Miss Saigon" productions playing around the world, and that everything works.

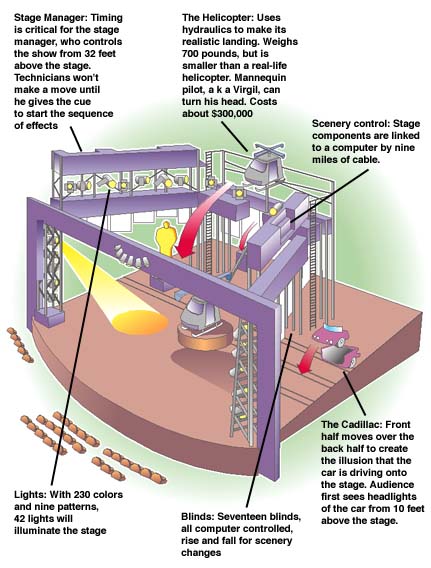

And when the show opens Thursday at the Blaisdell Concert Hall, the audience will be in the dark that behind the scenes there are more than a dozen PCs and Apple computers triggering more than 200 set changes, 59 automated scenery effects, 435 traditional lights, 42 Vari-Lights which can cast 230 colors in nine patterns to any point on the stage, a reproduction of a 1959 Cadillac convertible and a 700-pound scale model of a Huey helicopter with its animatronic pilot Virgil.

Sure, the two-hour show may be story driven, but "Miss Saigon" is a marvel of technology, especially for a traveling production which the high end/technology magazine Forbes ASAP calls "the biggest techno-theatrical production in Broadway musical history.""That means this show could never have been done without computers," says Kruse, who was born at Tripler Hospital and lived in Hawaii until age 13.

"A techno-theatrical production is not about the technology; it's theater enhanced by computer technology," Kruse said. "The movie 'Armageddon' is about computer technology; 'Titanic' is a story enhanced by it."

Kruse said "Miss Saigon" is a very complicated show to stage, and it is one of the largest touring productions on the road.

The Helicopter

The Cadillac

And when there is actually a road for the production to travel on, "Miss Saigon's" set fits into 17 48-foot semis. For the 2,500-mile ocean journey from Long Beach, Calif., to Hawaii, the show required 23 containers because these are a bit smaller than the semis, Kruse said.

Every piece is carefully numbered with specific arrival schedules so the staging and props and equipment can be unloaded in the most efficient order possible.

The "Miss Saigon" production carries with it "absolutely everything" it requires, including nine miles of cable, its own stage, and all support and back-up systems.

"We suspend our own grid with more than 100 chain hoists which basically are a heavy motor that uses chain instead of rope or cable," Kruse said. "The hoists are used to switch scenery during the show some 22 times."

Just what else is packed into all those containers?

There's the 18-foot tall, 300-pound Ho Chi Minh statue which required four months to create; 450 costumes; 60 hand guns, M-16's & AK-47's; 435 lighting instruments; four smoke and fog machines; 35 radio microphones; 95 speakers used in the sound system; 12 computers; the near life-sized helicopter; and the 1959 Cadillac reproduction.

In addition, the production uses about 1,600 pounds of dry ice a week to create fog.

There are 43 cast members and 18 orchestra members.

It's Kruse and the crew's duty to make sure the 59 automated effects "blend" and the 23 scene changes are "seamless."

Step in computer technology: As scenery wagons make their way onstage for set changes -- along embedded, automated cable-and-pulley tracks -- sensors are reporting their location to a computer at the rate of 10,000 times per inch. The wagons stop within one-fifth of an inch every time, every night, Kruse said.

The show is best known not just for its helicopter but for its empty stage surrounded by 19 huge Venetian blinds made out of a type of gauze, designed to look like rice paper, that lowers and raises to allow scenery to come on and off stage, Kruse said.

Despite dozens of set ups every year, Kruse said nothing is taken for granted. Thorough testing is done two-thirds through any load-in; a complete run through, with actors in costume, is even done the day of the first performance, Kruse said.

"We check that all the computers are working, we have lights to focus, scenery to check, get acquainted with local theater crew, and run-through some of the more important scene changes which requires precise timing for safety sake."That always includes running the highly publicized helicopter which is used for what Kruse said is "the trickiest high-tech effect" in "Miss Saigon": the nightmare sequence which recreates the Saigon evacuation off the United States Embassy roof in 1975.

"It's 8 minutes of action and very tricky," he said, because the 700-pound helicopter sits atop an 18-foot hydraulic arm with 5-foot rotors spinning. The aircraft comes down tipped at a 90-degree angle, Kruse explained.

"What's tricky is the whole combination of independent effects used to create the helicopter scene," Kruse said. Computers control the five motorized movements, up and down, left and right, pitch, roll and yaw.

"We have another motor to make the helicopter's rotors whirr," he said.

When technical glitches do occur, the production stage manager must keep the show running.

"Usually, the audience never really notices any problems," Kruse said. "There are dozens of crew eyes watching the show anticipating what to do if a problem occurs."

Click for online

calendars and events.