LINGERING PAST

State’s history

nurtures ethnic

animosity

The way people treated

each other through the years

is not forgottenDeLima reaching out to students

By Susan Kreifels

Star-Bulletin

Hawaii's tangled history of race relations -- starting when the first white people arrived, through plantation days, to the internments of Japanese-Americans during World War II -- complicates relationships among all races and ethnic groups today.

Caucasians first wrested land and culture from native Hawaiians, oversaw Asian laborers sweating on sugar plantations, and went home to all-white neighborhoods.

"Locals vs. haoles" is a phrase so often repeated it is almost a cliche in the islands. Occasionally, the feelings turn physical.

In 1989, at Mililani High School, an unprovoked beating by local youths of a German exchange student and his host led then District Judge George Kimura to lash out at the community for ignoring racial tensions. The bottom line of the attack, he said, was "the basic dichotomy within our state between locals and haoles."

"This may have had -- although I doubt it -- justification in the historical past, but it has no justification in our present multiracial society," Kimura said at the time.

But some sentiments die hard. Ryan Root, a Hawaiian-Japanese student at Kaimuki High, said he doesn't like haoles "who think they're better than us," and still feels the impact of injustices done to his Hawaiian ancestors.

"I don't hate haole people," the 16-year-old explained. "I just don't like what happened then. We would just like some land back."

Stories of "kill haole day" have circulated for decades, mostly among older generations. That's when word passed in school hallways that students who are haole -- a Hawaiian word which means "foreigner" but generally refers to whites -- could be in for a hard time. Some mothers of years past said they took the stories seriously enough to keep their children home.

'We are one large

dysfunctional family because we

still hold on to a lot of our

plantation kinds of attitudes.

The stories just keep being told,

the fears of our grandmothers.'

Lois-Ann Yamanaka

AUTHOR"Just about everyone in Hawaii is aware of the stories," said Department of Education spokesman Greg Knudsen. "But I've never seen any evidence that it actually existed."

On its face, the notion is intolerable -- and it's not an issue that students themselves raise when asked about racism in schools. But the persistent stories reflect the complex history of race relations here.

Davianna McGregor, a native Hawaiian and a University of Hawaii ethnic studies professor, said attitudes toward whites will be negatively colored until past injustices are atoned.

The islands have a "history of nonwhite people treated very poorly by Caucasians," she said. Augmenting the problem are newcomers who are "not used to being in a situation where white is a minority."

"People come and don't expect to assimilate to Hawaii, they expect Hawaii to assimilate to America," she said. "That's unacceptable."

The plantation era adds another layer of emotion. In his book "Cane Fires," Cornell University professor Gary Okihiro set out to challenge "the prevailing view of Hawaii as a mythical 'racial paradise.' "

His premise: a "systematic anti-Japanese movement" from plantation days through World War II led by plantation owners, the territorial government and the U.S. military.

Even among Asian-American plantation workers there were hierarchies based partly on skin color, said award-winning author Lois-Ann Yamanaka, author of the novel "Blu's Hanging."

Japanese and Chinese were on the top, she said, and "the darker your skin, the more like the African-American experience ... How can you not see it?"

Yamanaka, who also is a teacher, said the social classes and stereotypes formed among Chinese, Japanese and Filipino workers still hold, and students take those attitudes to school.

Author Jana Wolff feels "we are scared to talk about racism." Wolff, a Caucasian who has lived here for 10 years, adopted an African-Latino-American boy and wrote the 1997 book "Secret Thoughts of an Adoptive Mother," which topped local best-seller lists.

She said her son has been the target of racial taunting.

"Relative to the mainland, there's less animosity," she said. "But there is an unwritten, unspoken hierarchy of races."

She maintains hope though. She would like to see diversity and tolerance training in every school curriculum, and feels Hawaii's rich mix of people give it all the ingredients to become the "model of tolerance education."

Given the historical context, perhaps simpler said than done -- but a goal that's hard to criticize from any angle of the racial spectrum, and one which Hawaii, despite its difficulties, has long professed.

CHEER UP

DeLima reaching out

to studentsLocal comedian serves as a role model,

By Susan Kreifels

but he sees a change in attitudes

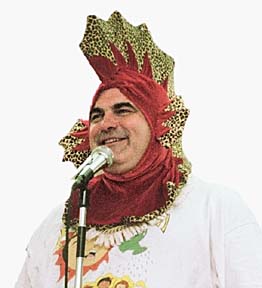

Star-BulletinIf you want to hear a joke about a frugal Chinese, bookish Japanese or the light bulb-challenged of any race, Frank DeLima is your man.

DeLima is the king of ethnic humor in Hawaii, a comedian whose takes on racial stereotypes can pretty much be a gauge of residency: Laugh, and it shows you've been in Hawaii for a while. Laugh at a joke about your own race, and you've been here longer.

The comedian serves as a Department of Education role model for students on how to get along. He has spoken at public elementary schools for years. "It's important to laugh at yourself," he said. "It's a sign of humility."

Laughing at cultural stereotypes, he believes, helped lead plantation workers out of their tight ethnic circles to intermarry, socialize and trust one another. He has made a career out of giving them that opportunity and keeping their pidgin English alive, sometimes at the risk of offending his own "Portagee" community.

'It's important to laugh

at yourself. It's a sign

of humility.'

Frank DeLima

COMEDIANBut DeLima senses times are changing.

In his school talks, he emphatically tells his audiences not to name-call or tease, especially with students new to the islands who need to be shown the aloha spirit and taught "our way."

To students who are the butt of jokes or names, he advises walking away rather than "carrying a chip on their shoulder their whole life."

DeLima begrudgingly says his comedy style likely is on the way out as newcomers arrive and the texture of the population changes.

He thinks newcomers should try to learn about Hawaii's home-grown culture before judging and criticizing, and adapt to the ways that exist.

"People bring their own prejudices and whatever is happening in other places to Hawaii, and cause all these uncomfortable situations," he lamented. "All this sensitivity will cause a lot of negativism, and Hawaii will be like everywhere else, with prejudice and violence."